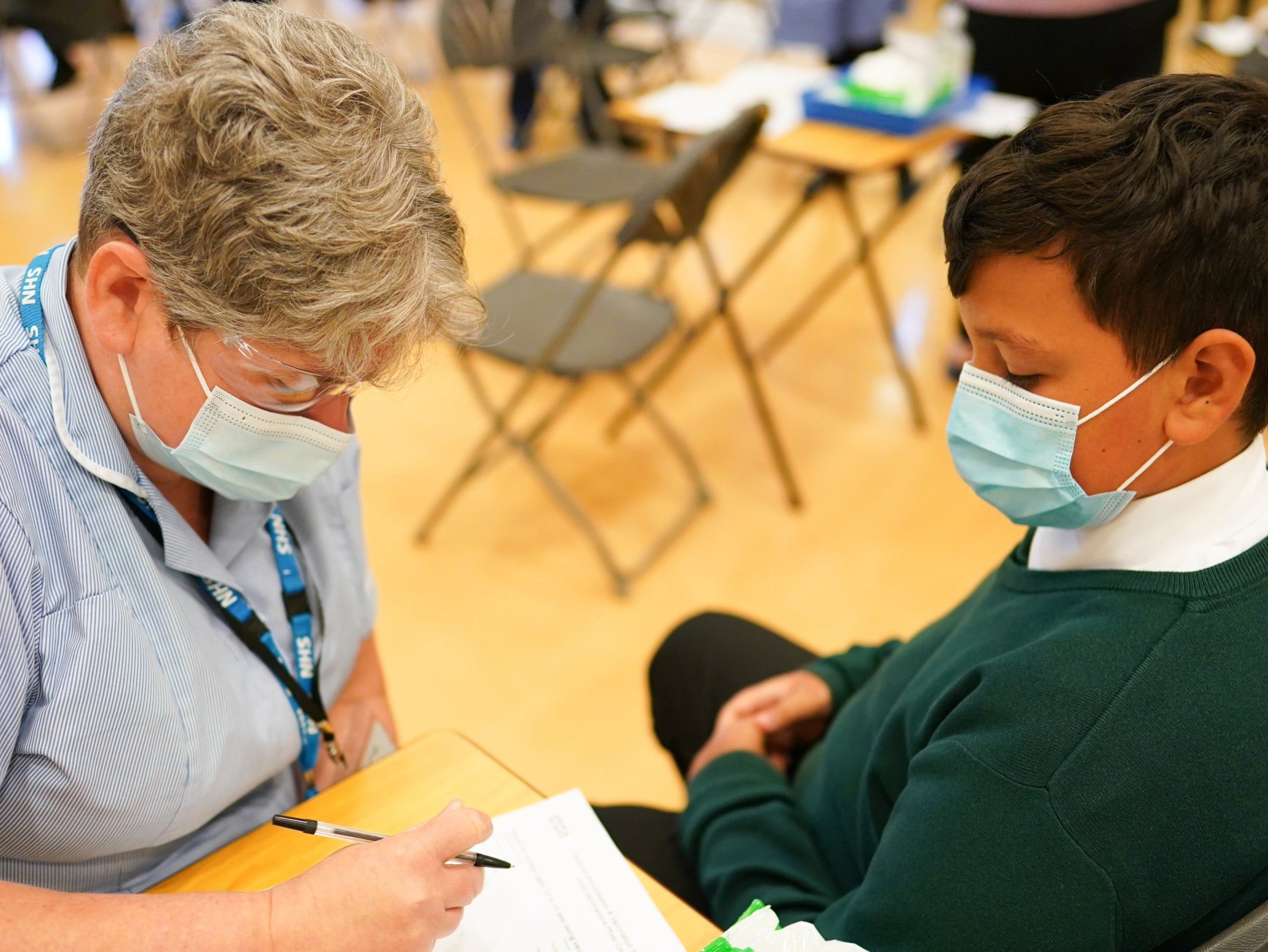

Younger children less willing to be vaccinated against Covid-19, study finds

Young people who are most hesitant about having the vaccine use social media more, research finds

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Younger children are less willing to receive a Covid-19 jab than older teenagers, a new study has shown, as experts said more work is needed in improving access to vaccine information for these groups.

Some 36 per cent of nine-year-olds and 51 per cent of 13-year-olds are willing to be vaccinated, compared to 78 per cent of 17-year-olds, according to a study that surveyed primary and secondary school students in England.

The research, led by scientists at UCL and the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, also found that those less willing to be jabbed often come from the most deprived backgrounds, believe they have already had Covid-19, and do not feel a part of their school community.

Sir Andrew Pollard, a professor of paediatric infection and immunity at the University of Oxford, said the findings suggested that not enough information and support had been provided via the appropriate platforms, such as social media, for children and young teenagers.

“This study is immensely important as its highlighting that there is some indecision particularly in the younger teenagers,” he told a science briefing on Monday. “We’ve missed this really important group in making sure they have access to information.

“I guess that may well be because, rightly, our focus over the last year has been on adults where the highest rates of disease are.”

The study, which ran from May to July of this year, surveyed more than 27,000 students from 180 schools across Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire, and Merseyside.

The only large-scale study of its kind, the survey asked children aged between nine and 18 about their views on being vaccinated against Covid-19.

Overall, half were willing to be vaccinated, 37 per cent were undecided and 13 per cent wanted to opt out. But the older the pupil, the more likely they were to accept the offer of a vaccine.

The high number of older teenagers willing to receive a jab is comparable with the adult population, the researchers said, and reflects greater access to a wider pool of both traditional and non-traditional information sources.

“Younger children more often defer to their parents, or primary caregivers, for decisions about healthcare and vaccination,” said Mina Fazel, an associate professor in child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of Oxford.

“Our data shows how important it is for good quality, accessible information to be provided to better enable our younger populations to understand more about the Covid-19 vaccine and its effects.”

Prof Fazel said more needed to be done in utilising the types of social media platforms that are commonly used by children and young adolescents, such as TikTok and Snapchat. This is “an area we need to learn about,” she said, adding that it is “at our peril to ignore it”.

The study found that young people who are most hesitant about having the vaccine use social media more.

“They don’t access their information by reading the newspaper or watching broadcast news,” said Prof Pollard. “We need to provide information to this age group and we need to use the structures they’d access.”

Russell Viner, a professor of adolescent health at the UCL Institute of Child Health in London and one of the study’s co-authors, said it was “essential” that authorities involved in the current vaccination of 12 to 15-year-olds also “reach out and engage with young people from poorer families and communities with lower levels of trust in vaccination and the health system”.

He said that England’s school-based vaccination programme, with more than three million young adolescents set to be offered a single dose of the Pfizer vaccine in the coming weeks, is “way of helping reduce these health disparities.”

However, Prof Viner added, the “teenagers who are least engaged with their school communities may need additional support for us to achieve the highest uptake levels.”

Addressing the limitations of the study, Prof Fazel said that the wider patterns of vaccine hesitancy across England are constantly changing and could have shifted since the conclusion of the study. She said the research also missed certain year groups and didn’t ask children about their parents’ views on vaccination.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments