The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Second concussion in quick succession interrupts brain's ability to repair damage, finds study

Two head injuries within 24 hours prevents immune system from launching recovery of destroyed blood vessels

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have recorded how suffering two concussions in 24-hours prevents the regeneration of ruptured blood vessels in the brain’s protective lining and can lead to damage becoming permanent.

In a finding which could pave the way for treating brain damage after a stroke or serious head injury, US researchers recorded the role the immune system plays in recovery.

Around half of patients who experience a concussion will have damage to blood vessels in the meninges, the connective tissues that line and protect the brain and spinal cord.

This damage causes the blood vessels' contents to leak out, and can ultimately cause the death of the brain cells beneath the protective lining.

In the majority of patients damage repairs naturally within three weeks, but the authors observed 17 per cent of their patients still had signs of damage when given an MRI scan three months later.

“Following a head injury, the meninges call in a clean-up crew, followed by a separate repair crew, to help fix damaged blood vessels,” said Dr Dorian McGavern, senior author of the study published in Nature Immunology today.

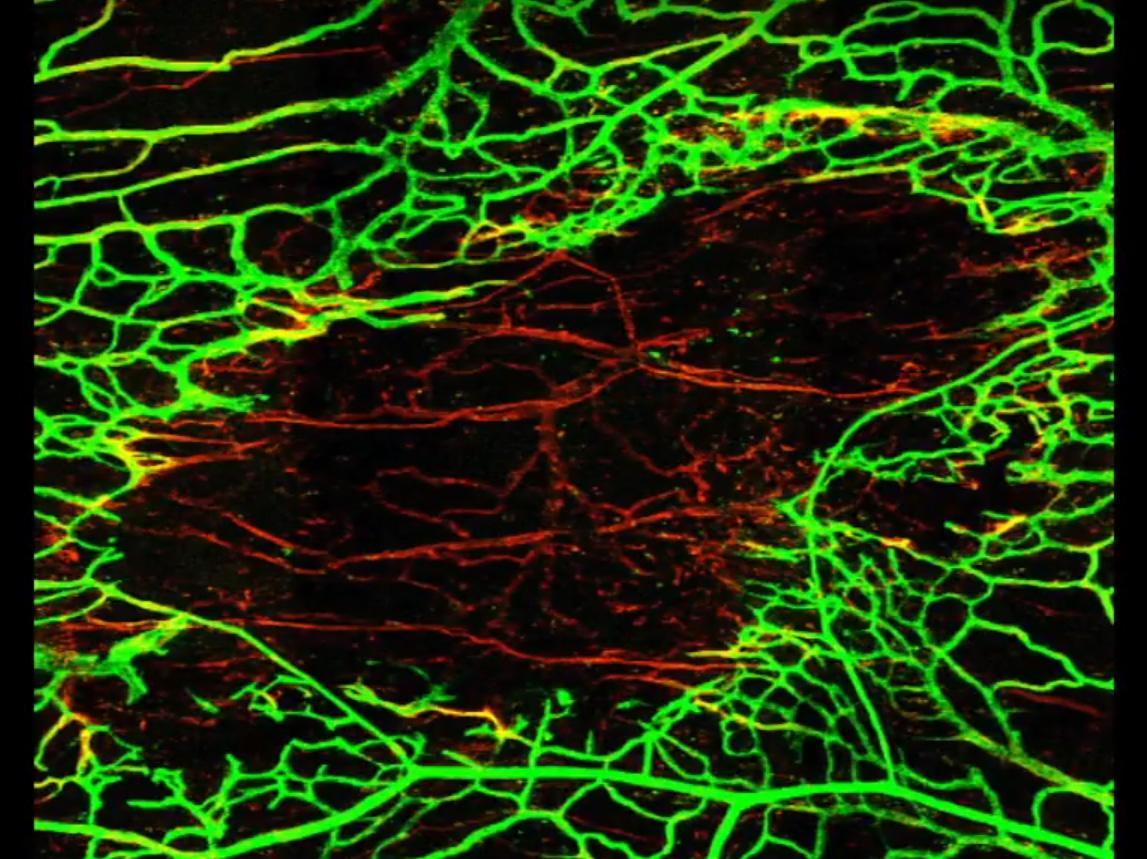

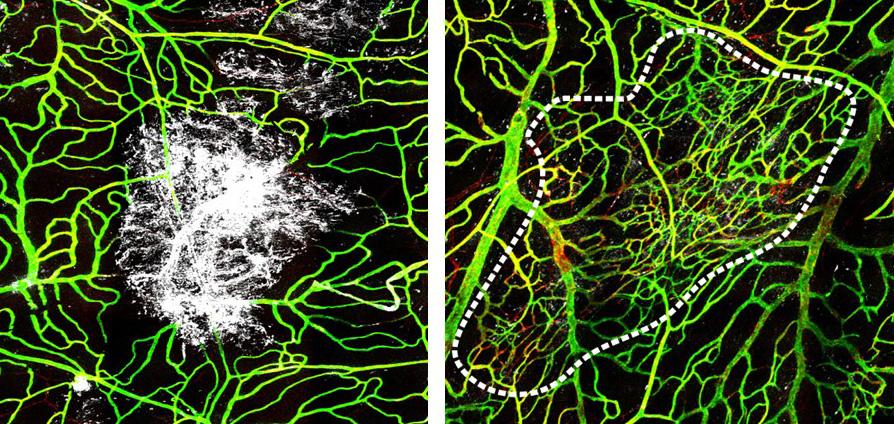

To study the brain’s repair systems in-depth the team from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke scanned the brains of mice and used coloured dyes to show the blood vessels and white blood cell repair teams.

In the first day after a brain injury they witnessed cells, called inflammatory monocytes, entering the meningeal tissue to clear away dead cells.

This took around four days and the monocytes were followed by a second type of white blood cell which repaired and restored the blood vessels that had been lost, a process which lasted one to three weeks.

But they found that when the mice suffered a second head injury, the initial inflammatory stage was heightened but there was no recovery of the meninges.

A major study recently showed how a severe concussion in your twenties can increase the chances of getting dementia in the next 30 years by two-thirds.

The American National Football League was forced to make a $765m (£534m) payout to injured athletes with long-term health effects from multiple career concussions.

Other contact sports, like rugby, introduced independent concussion screening and protocols to remove players from the field to prevent a repeat blow to the head.

“The timing of a second head injury may determine whether the meninges can be repaired,” Dr McGavern said.

“We have shown on a cellular level, that two or more head injuries within a very short amount of time can have really dire consequences for the brain lining and its ability to repair.”

Athletes with post-concussion syndrome, where the repair has been interrupted, can suffer months of headaches, nausea and dizziness as well as a heightened sensitivity to further knocks.

The team believe that in their patients who did not fully recover at the time of their second MRI scan, the repair process may have been disrupted by a second head knock or injury in the first phase of repair.

Further experiments suggested that a wound-healing enzyme, matrix metalloproteinase-two, which unglues the cells in the meninges plays a crucial role in clearing space for new blood vessels to form.

Understanding the timing of its release and how it and other chemicals are deployed in the brain lining’s “remarkable” self-repair effort could lead to better treatments for patients with serious or incomplete healing after an injury, said Dr McGavern.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments