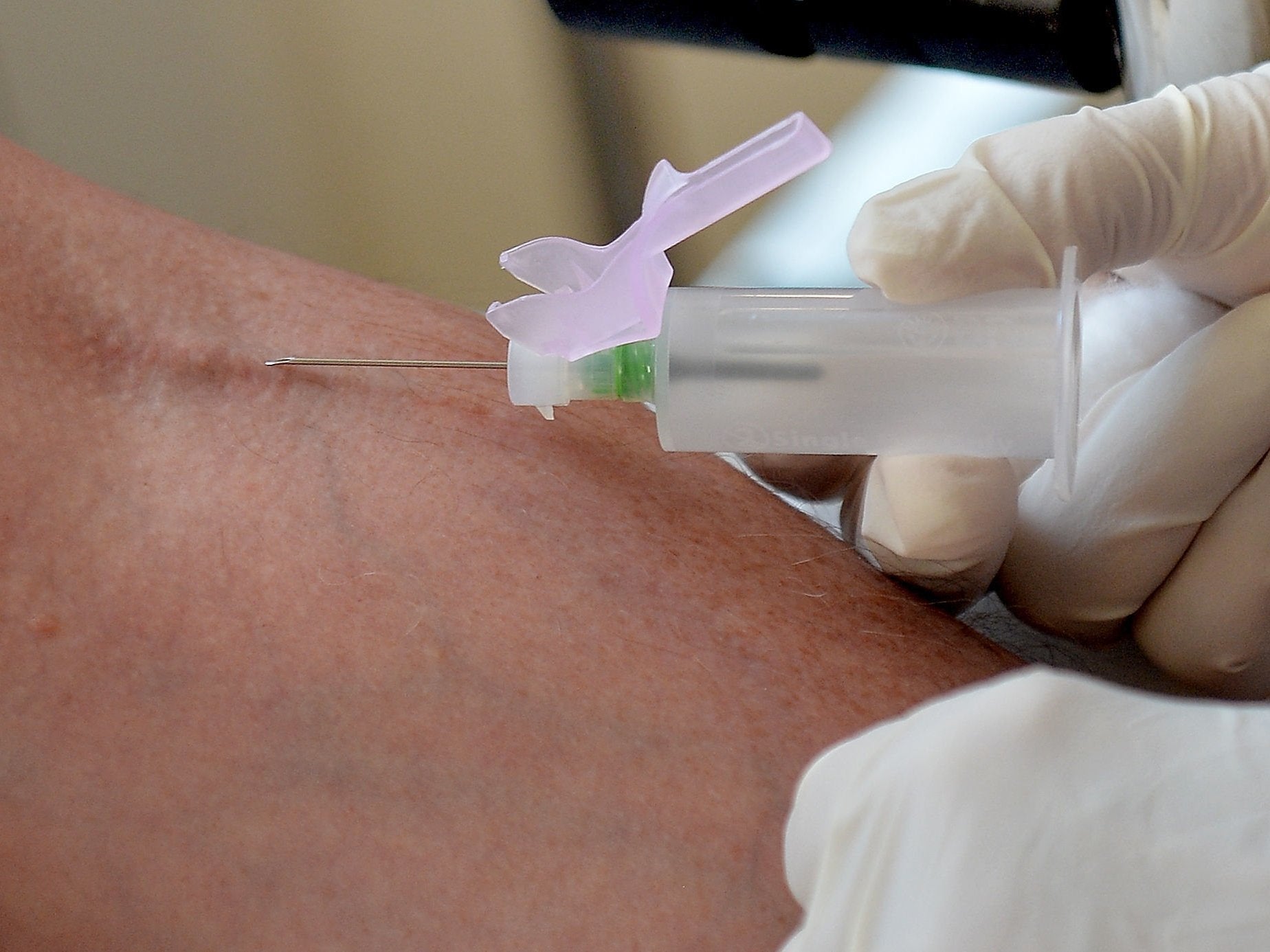

Blood test for chronic fatigue syndrome could speed diagnosis, study says

‘Excitingly, they appear to have discovered a distinguishing feature of ME/CFS, and one that can be measured simply and cheaply’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The first blood test capable of diagnosing chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) could be in sight, experts have said.

US researchers, led by Stanford University, have found a way to measure differences in the electrical signals given off by cells in the immune systems of people with CFS, also known as ME or myalgic encephalomyelitis.

In small pilot studies the test accurately diagnosed samples from people with ME/CFS from among healthy volunteers, though larger trials will be needed to see if it can distinguish between other causes of fatigue.

ME/CFS is diagnosed based on symptoms, which include debilitating fatigue after physical exertion, muscle and joint pain, sensitivity to light and the exclusion of other causes.

However, the lack of a conventional test means sufferers often face unwarranted stigma from the public and health professionals, the Stanford team said.

“Too often, this disease is categorised as imaginary,” said Professor Ron Davis, a senior author of the study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“All these different tests would normally guide the doctor towards one illness or another, but for chronic fatigue syndrome patients, the results all come back normal.”

Professor Davis was motivated to research the condition as his son has been living with CFS for a decade.

Recent research has provided the strongest evidence to date that the condition is caused by prolonged dysfunction of the immune cells, and many cases begin after a seemingly minor illness.

For the study Professor Davis and colleagues developed a “nanoelectric assay”, which is capable of measuring minuscule energy changes in cells in the blood to gauge their health when exposed to stress – in this case salt.

In trials with 20 ME/CFS sufferers and 20 healthy volunteers, the salt caused a big spike in the cellular energy in the samples taken from people with chronic fatigue, suggesting they’re overreacting to this stress.

This was enough to accurately identify the 20 people with ME/CFS in the pilot trial.

“We don’t know exactly why the cells and plasma are acting this way, or even what they’re doing,” Professor Davis said. “But there is scientific evidence that this disease is not a fabrication of a patient’s mind.

“We clearly see a difference in the way healthy and chronic fatigue syndrome immune cells process stress.”

If this turns out to be a reliable test for ME/CFS it could also help guide research into new treatments to reduce this immune response, as until now it wasn’t possible to tell if drugs were having an effect at the cellular level.

“Excitingly, they appear to have discovered a distinguishing feature of ME/CFS, and one that can be measured simply and cheaply,” said Professor Chris Ponting, principal investigator at the UK Medical Research Council’s Human Genetics Unit.

While the findings need to be replicated, tested in other groups and ideally be able to show the severity of ME/CFS, Professor Ponting added: “These results also now narrow down the possible molecular and cellular causes of this devastating set of conditions.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments