Childhood poverty has a lasting impact on developing brain, finds study

Brains of children whose parents have more education and so-called 'white collar jobs' are bigger in key areas

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Growing up in a less well-off family may negatively impact the brain, according to research showing how socioeconomic status can have a lasting impact on a person’s development.

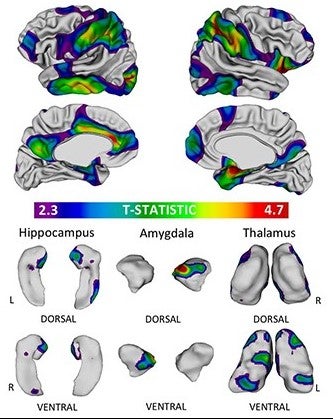

US researchers found brain regions responsible for learning, language and emotional development tended to be more complex in people whose parents were educated to a higher level or who worked in professional rather than manual jobs.

Brain scans from hundreds of young people show these effects are stable throughout childhood and adolescence, the National Institute of Mental Health researchers found.

This means targeting additional support in the pre-school years could help minimise inequalities it causes in a host of life outcomes, including mental health and academic achievement, the researchers added.

“Early brain development occurs within the context of each child’s experiences and environment, which both vary significantly as a function of socioeconomic status,” said lead author Cassidy McDermott and colleagues.

In childhood, socioeconomic status, which encompasses income as well as opportunities and a string of other factors, has been linked to a range of mental health, cognitive development, and academic outcomes.

“Socioeconomic status may exert some of its effect on cognition by altering structural brain development, particularly in regions associated with language and learning,” Ms McDermott said.

“However, it is important to note that this pathway represents only one possible set of interactions between childhood environment, anatomy, and cognition.”

For the study, published in the Journal of Neuroscience, the researchers looked at 1,243 brain MRI scans from more than 623 young people aged between five and 25. While the socioeconomic score used did not take account of family income in the earliest measurements this is another determinant of socioeconomic status and also correlates with parental occupation and education factors.

Previous studies have shown links between parental occupation and earnings and an overall increase in the volume of the brain’s grey matter.

However the study takes this further and shows that higher socioeconomic status in early childhood has a pronounced effect on two areas of the brain, the thalamus and striatum.

The thalamus is a key region in the centre of the brain involved in the transmission and processing of sensory information, and a larger thalamus volume is closely linked with quicker thinking and higher verbal IQ.

While differences in size and complexity of these brain regions tracked with socioeconomic status, and this has been shown to predict future life outcomes the study does not prove one causes the other.

Many other factors will play a role in early year;s development and future outcomes, and McDermott and colleagues say they hope understanding the roots in anatomy can help reduce variation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments