Human trials start with cancer treatment that primes immune system to kill off tumours

'In the mice, we saw amazing, body wide effects, including the elimination of tumours all over the animal'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Human trials have begun with a new cancer therapy that can prime the immune system to eradicate tumours around the body.

The treatment that works similarly to a vaccine is a combination of two existing drugs, of which tiny amounts are injected into the solid bulk of a tumour.

It works by reactivating immune cells suppressed by the cancer, triggering a body wide immune response which was able to “eliminate tumours all over the body” even ones unrelated to the initially treated cancer, according to researchers at Stanford University who developed it.

It is thought that it could be used to prevent cancer returning after surgery.

Following successful trials with mice, the researchers said it was now ready to be tested on humans.

One of the immunotherapy drugs used is already approved for use in humans, while the other is undergoing trials.

Individually they have to be matched to a particular type of cancer, but when used in combination it appears they have a much more potent and wide-ranging impact.

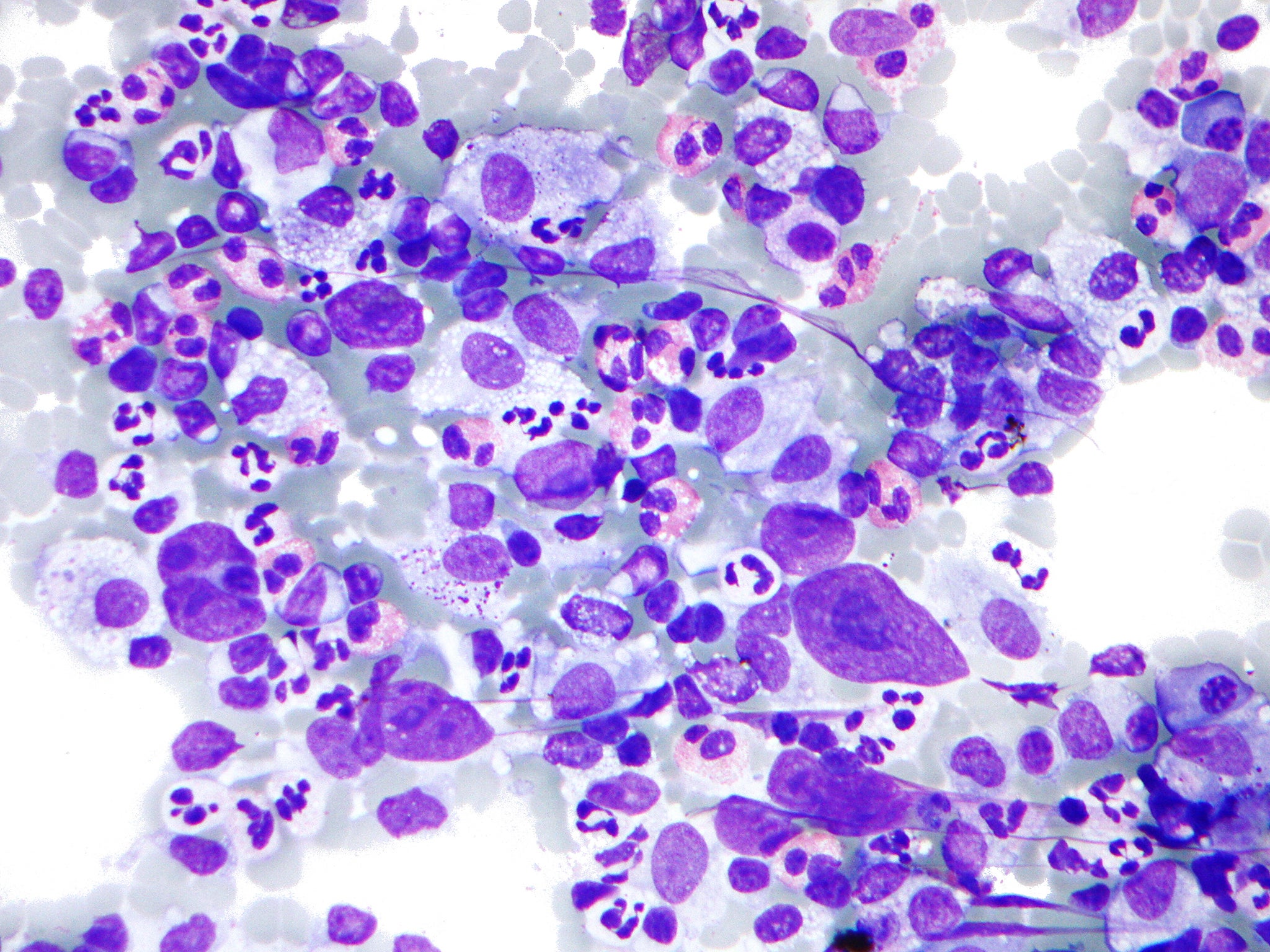

A clinical trial began last month to test the effects in human patients with lymphoma – a cancer that infects the white blood cells which travel around the body fighting infection and can therefore rapidly spread.

If the results from mice can be replicated in humans it could have significant potential.

“Our approach uses a one-time application of very small amounts of two agents to stimulate the immune cells only within the tumour itself,” said Dr Ronald Levy a professor of oncology at Stanford University School of Medicine.

“In the mice, we saw amazing, body wide effects, including the elimination of tumours all over the animal.”

While the immune system is able to detect cancer cells and set itself to attack it with killer T white blood cells, tumours are able to neutralise the attackers once they latch on and continue to grow.

But, treating the tumours with a 1 microgram dose (one millionth of a gram) of the immunotherapy drugs reawakened these no engulfed cells and allowed them to begin attacking the cancer again, at the treated site and elsewhere.

The treatment cured mice of lymphoma in 87 out of 90 cases and though three mice saw a return, this was successfully treated with a second dose and similar results were seen in mice with breast, colon and melanoma cancers.

The human trial will include 15 lymphoma patients and if successful Dr Levy sees this treatment as a way to significantly reduce the chances of a cancer returning, by injecting the immunotherapy cocktail before surgery to remove the main tumour mass.

“I don’t think there’s a limit to the type of tumour we could potentially treat, as long as it has been infiltrated by the immune system,” Levy said.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments