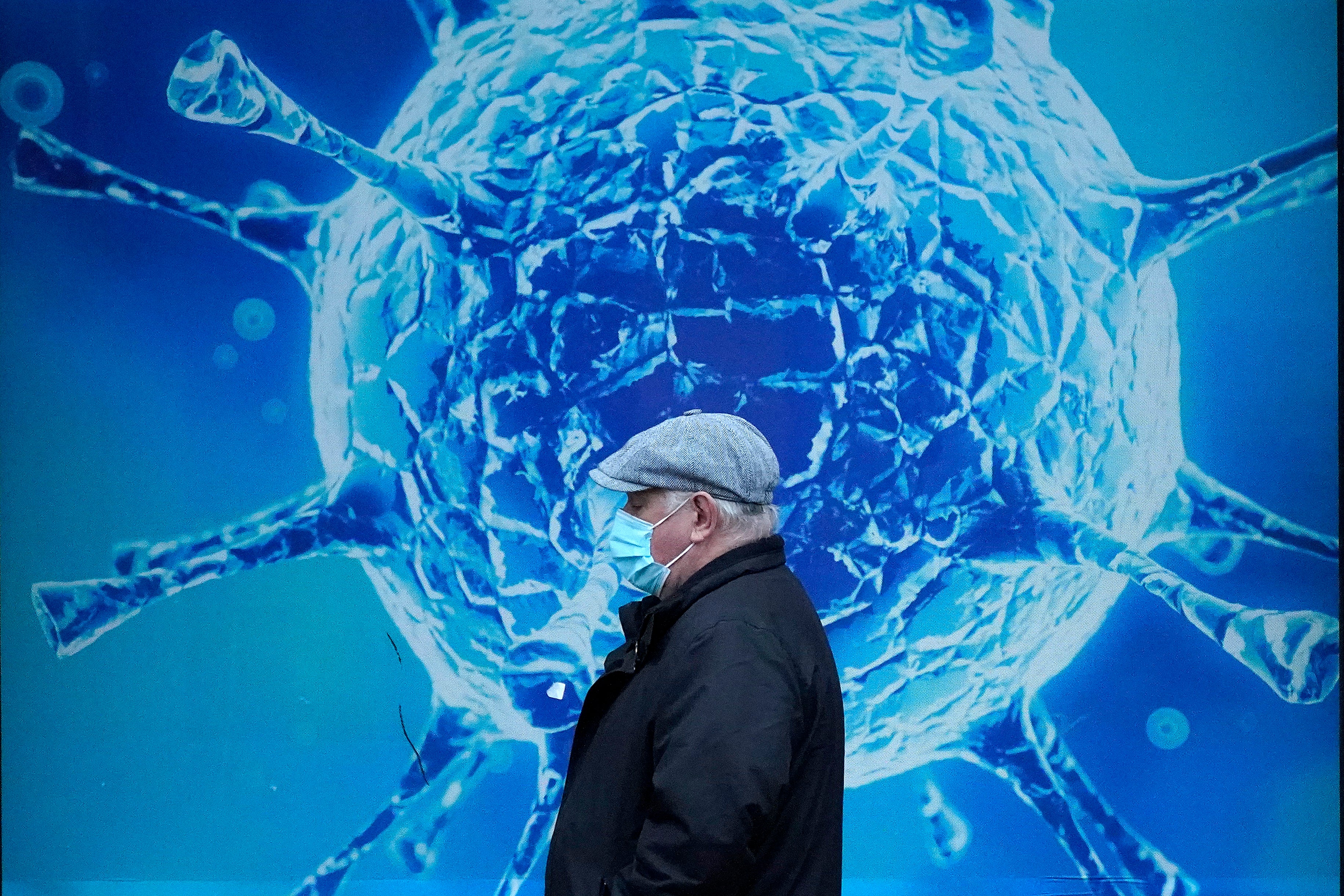

New Covid variant: Everything we know

B.1.1529 has ‘incredibly high’ number of mutations on its spike protein

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What is the new variant?

A new variant of Covid-19 has emerged, known as B.1.1529. The World Health Organisation relies on the Greek alphabet to name new variants of concern, which means B.1.1529 could eventually be called Nu, as this is the next available letter.

The variant, which descends from the B.1.1 lineage, has an “incredibly high” number of mutations, experts say, with fears that it is highly transmissible and effective at evading the body’s immune response.

B.1.1529 has 32 mutations located in its spike protein. These include E484A, K417N and N440K, which are associated with helping the virus to escape detection from antibodies.

Another mutation, N501Y, which is found in the spike protein, appears to increase the ability of the virus to gain entry to our cells, making it more transmissible.

Where did it come from?

The variant was first spotted in Botswana on 11 November, where three cases have now been recorded.

Meanwhile in South Africa, where the first case was spotted on 14 November, 22 cases have now been recorded, according to the National Institute for Communicable Diseases.

More cases are expected to be confirmed in the country as sequencing results come out, with the South African government saying on Thursday that many of the cases of B.1.1.529 were located in Gauteng province. It has also requested an urgent meeting with the WHO’s Covid technical working group.

An additional case has been identified in Hong Kong, involving a 36-year-old traveller – who had stayed in South Africa from 23 October to 11 November – and who tested positive three days into quarantine on his return home.

Scientists have said that the variant has more changes to its spike protein than any other they have seen, with suggestions that it possibly emerged from an immunocompromised person who harboured the virus for a long period of time, possibly someone with undiagnosed HIV/AIDS.

Professor Francois Balloux, the director of the Genetics Institute at University College London, said that the variant’s mutations are in “an unusual constellation” that “accumulated apparently in a single burst”.

He explained that this indicates it could have evolved during a “chronic infection of an immunocompromised person, possibly in an untreated HIV/AIDS patient”.

So far, no cases of the variant have been recorded in the UK.

Is it resistant to vaccines?

The spike proteins which coat the outside of the Covid virus allow it to attach and gain entry to human cells. The vaccines train the body to recognise these spikes and neutralise them, therefore preventing infection of cells.

The 32 mutations detected in the new variant’s spike protein will change the shape of this structure, making it problematic for the immune response induced by the vaccines.

These mutations can make the spike protein less recognisable to our antibodies. As a result, they won’t be as effective at neutralising the virus, which is then able to slip past immune defences and cause infection.

Should we be concerned?

Scientists have mixed opinions over whether or not we should be worried about the latest variant.

Dr Tom Peacock, a virologist at Imperial College London, warned that the variant could be “of real concern” due to its 32 mutations in its spike protein.

However, Prof Balloux said that at the moment there is “no reason to get overly concerned.”

Taking to Twitter, Dr Peacock wrote that the variant “very, very much should be monitored due to that horrific spike profile” which could mean that it is more contagious than any other variant so far.

He said: “Export to Asia implies this might be more widespread than sequences alone would imply.

“Also the extremely long branch length and incredibly high amount of spike mutations suggest this could be of real concern (predicted escape from most known monoclonal antibodies).”

But Dr Peacock said that he “hopes” the variant will turn out to be one of these “odd clusters” and that it will not be as transmissible as feared.

Meanwhile, Prof Balloux said that “it is difficult to predict how transmissible it may be at this stage.”

The professor explained: “For the time being, it should be closely monitored and analysed, but there is no reason to get overly concerned, unless it starts going up in frequency in the near future.”

Dr Meera Chand, the Covid-19 incident director at the UK Health Security Agency, said that the status of new Covid variants worldwide is constantly being monitored at random and that a small number of cases with “new sets of mutations” were “not unusual.”

She explained: “As it is in the nature of viruses to mutate often and at random, it is not unusual for small numbers of cases to arise featuring new sets of mutations. Any variants showing evidence of spread are rapidly assessed.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments