The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

The number of cases of H5N1 bird flu is growing - but can it be caught by eating chicken?

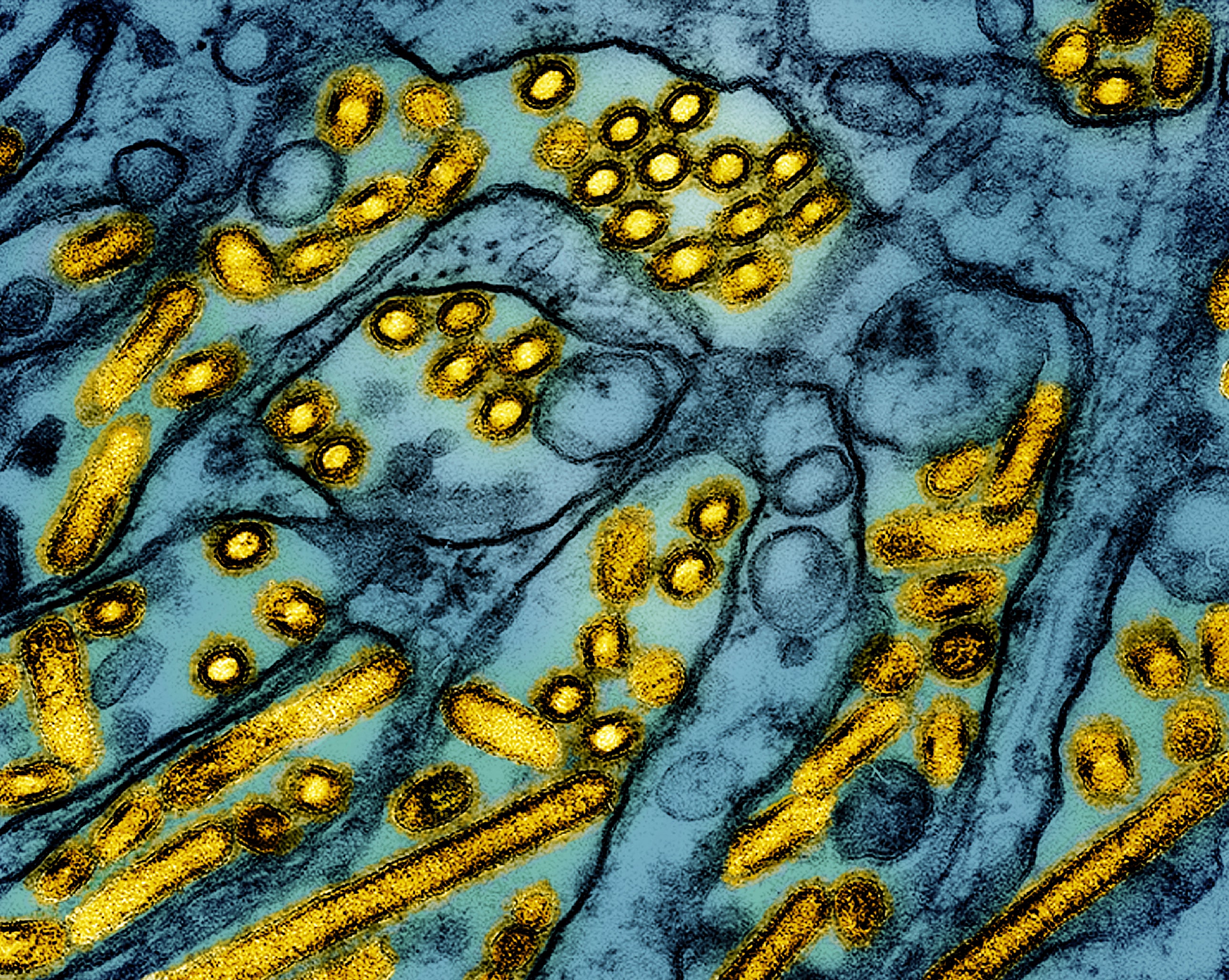

H5N1 bird flu has infected more than 50 people across seven states, with cases steadily climbing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As the number of human bird flu cases have continued to rise across the US, H5N1 infections have sparked near fears about the nation’s response and the possible threat of another pandemic.

The virus is spread to humans via several pathways. On a farm, for example, workers can inhale infected particles, pick up germs from sick animals and other surfaces and then touch their faces and eyes, and drink raw milk from cows.

Those who have had no contact with infected poultry or other sources of contamination are thought to be at very low risk of infection. No infections have been reported from eating properly cooked poultry or poultry products or proper handling of poultry meat.

The number of confirmed cases climbed to at least 53 this week, after new H5N1 infections were reported in California and Oregon. The majority of those cases were in people who worked with or around infected animals.

The continual spread of the virus, which has stricken 30 percent of the Golden State’s dairy herds, is sparking fears about the nation’s response and raising the possible threat of another pandemic.

In 2009, H1N1 caused the first global flu pandemic in 40 years, with the first infections detected in California. More than 12,000 people died around the US, and nearly 61,000 people were infected. The “pig flu” was constantly in headlines as communities tried to track the number of sick and dead from the contagious virus.

Now, more than 15 years later, social media users have called on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to provide vaccines and other protection for anyone who could be at risk of exposure to “bird flu” H5N1.

And, of the cases reported in the Western Pacific Region from January 2003 through this past September, the World Health Organization says there was a case fatality rate of 54 percent.

The US response to the virus came under fire on Tuesday in an op-ed published in The New York Times. South Africa’s director of the Center for Epidemic Response and Innovation said he was watching its spread “with dread,” calling it a “serious pandemic threat.”

“And yet, the US response appears inadequate and slow, with too few genomic sequences of H5N1 cases in farm animals made publicly available for scientific review,” Dr. Tulio de Oliveira wrote. “Failure to control H5N1 among American livestock could have global consequences, and this demands urgent attention. The United States has done little to reassure the world that it has the outbreak contained.”

However, as states have reported additional infections in farmworkers and Canada health authorities said a teenager was left in critical condition after infection, officials have maintained that risk to the public remains low. The CDC assured it is monitoring the situation carefully.

The virus that infected the Canadian teen underwent mutational changes that would make it easier for that version of H5N1 to infect people, scientists told STAT News. But, there’s not evidence they infected anyone else.

While US cases in humans and animals have increased, with Hawaii reporting its first outbreak in poultry on a backyard farm, the agency also noted that genetic sequencing from cases at poultry farms in Washington had identified a change that could reduce influenza viruses’ susceptibility to neuraminidase inhibitor antiviral drugs, such as the treatment Tamiflu.

“Slightly reduced susceptibility is NOT the same as resistance. This change is unlikely to have meaningful impact on the clinical benefit of oseltamivir, which is recommended antiviral treatment of H5 bird flu,” the CDC noted.

Drug resistance, also known as antimicrobial resistance, occurs when bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites no longer respond to antimicrobial medicines that are designed to defeat them. As a result, infections become difficult or impossible to treat. Drug resistance is a natural process that occurs over time through genetic changes in pathogens.

In the US, more than 2.8 million antimicrobial-resistant infections occur each year, and a 2019 CDC report found that more than 35,000 people die as a result.

Earlier this year, the CDC said it was tracking “dual mutant” strains of H1N1 influenza in US patients. The strains had genetic changes that could cut the effectiveness of the main flu antiviral drug.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments