Artificial ovary could allow women to become mothers after cancer treatment without risk, say scientists

Immature egg cells can develop successfully on an 'ovarian scaffold' stripped of the DNA and components that make up its living cells

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.An artificial ovary that can grow immature eggs into a fertilisable cell fit for implantation could one day let women become mothers after fertility-destroying cancer treatment, scientists have said.

Researchers from one of the leading fertility centres in Europe, Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen, say they have demonstrated the world’s first working “bio-engineered” human ovary in early animal trials.

Currently women will have eggs frozen before chemotherapy or radiotherapy, which can destroy the viability of the cells.

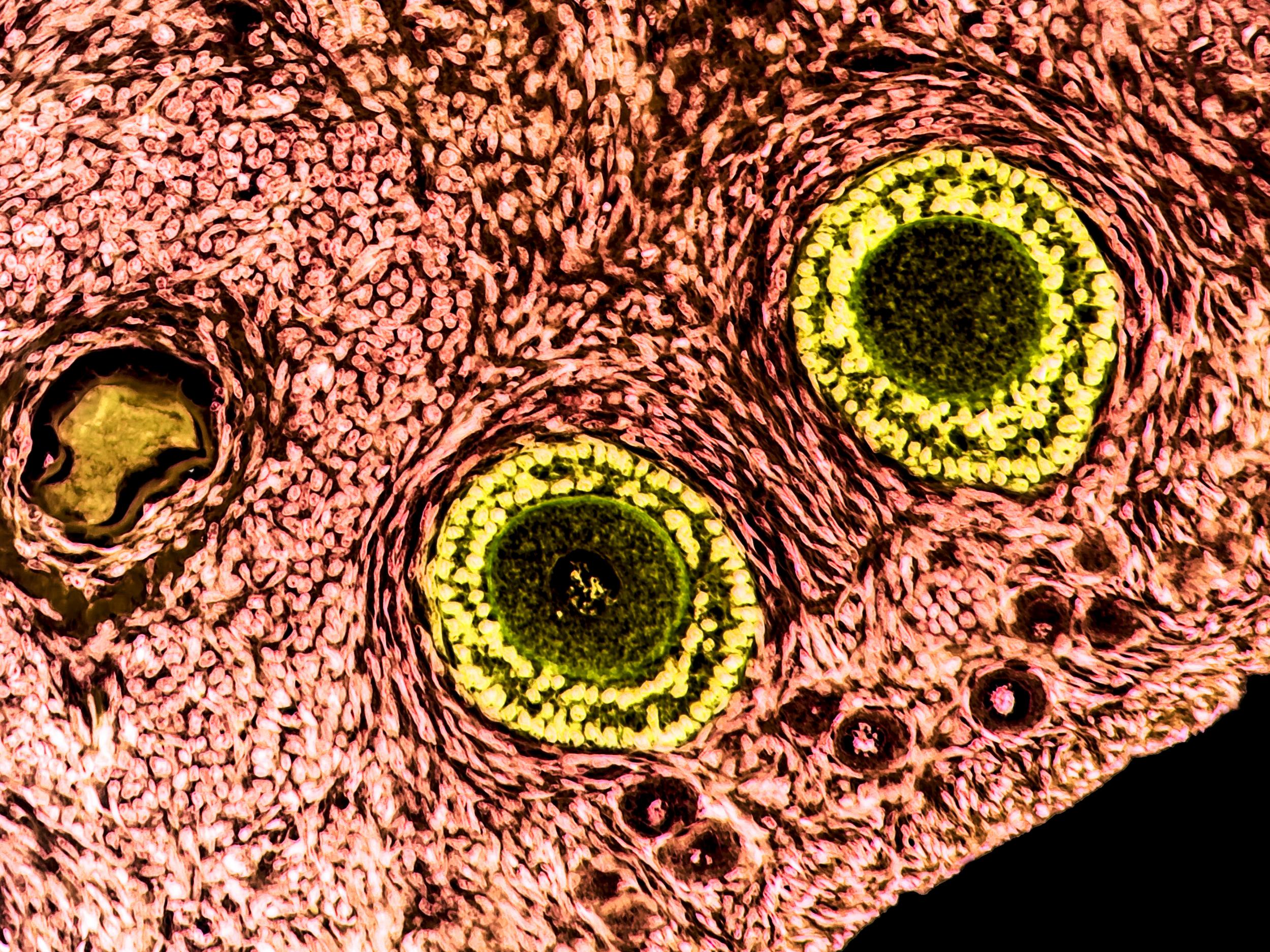

Prepubertal girls or women who need urgent treatment before they produce eggs, rely on ovarian tissue, which contains thousands of immature eggs in fluid-filled sacs called follicles, to be preserved instead with the aim of transplanting it after treatment.

However, if there is a risk of any cancerous cells remaining in preserved tissue, reimplantation could be deemed too risky.

The Danish technique offers a way to avoid this, and potentially improve on IVF and other techniques as more potential eggs could be preserved and would develop naturally if they can be reimplanted.

The team used a chemical process to strip the ovarian tissues’ cells of DNA and other features which could contain the faulty instructions for cancer cells’ unconstrained growth.

They then implanted immature egg cells into this empty ovarian “scaffold”.

The team showed that the immature eggs and tissue scaffold could reintegrate and survive in this scaffold, and it could then be grafted into a living host – in this case a mouse.

In theory the eggs would begin to mature and release each month in line with the hormone cues of the menstrual cycle.

“This is the first time that isolated human follicles have survived in a decellularised human scaffold and, as a proof-of-concept, it could offer a new strategy in fertility preservation without risk of malignant cell re-occurrence,” said Dr Susanne Pors, who led the Rigshospitalet team.

Dr Pors added that the risk of cancer returning from reimplanted ovarian tissue is “real”, though her team and others have found the chances are low.

It comes after a UK team were the first to take immature cells from follicle to mature eggs outside of the body, but without an ovarian scaffold that could allow follicles to be reimplanted and develop naturally.

The latest study has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal and is presented at the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) annual meeting in Barcelona on Monday.

But independent doctors said it was “groundbreaking” work, although the process now needs to be refined and shown to be safe in humans – which will take several years.

“This is an extremely important advance in the field of fertility preservation,” said Professor Adam Balen, professor of reproductive medicine and surgery at Seacroft Hospital, Leeds.

“The ability to successfully create a ‘new ovary’, by removing any tissue that might potentially reintroduce the cancer and fashioning a scaffold on which to grow the egg-containing follicles, allows the reimplantation of a ‘safe’ ovary, with the potential to successfully restore fertility.”

Dr Stuart Lavery, a consultant gynaecologist at Hammersmith Hospital, said: “If this is shown to be effective, it offers huge advantages over IVF and egg freezing.

“Because potentially these small pieces of tissue will have thousands of eggs and clearly, if it does work, there’s the advantage of then getting pregnant the old-fashioned way.

“We are some years away from that, and so IVF and egg-freezing is here now and will be with us for several years, but if this works it has dramatic potential.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments