The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Scientists discover why many Alzheimer’s drugs fail and identify one that may work

'There haven’t been any new drugs last 15 years, so it’s very promising to have uncovered a reason why some of that research may have failed'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A “vicious feedback loop” at the heart of Alzheimer’s disease may explain why so many drug trials hoping to treat this condition fail, according to a new study.

The same research found that a clinically approved drug that appears to break this cycle has the power to protect against memory loss in mice, providing hope for a future treatment.

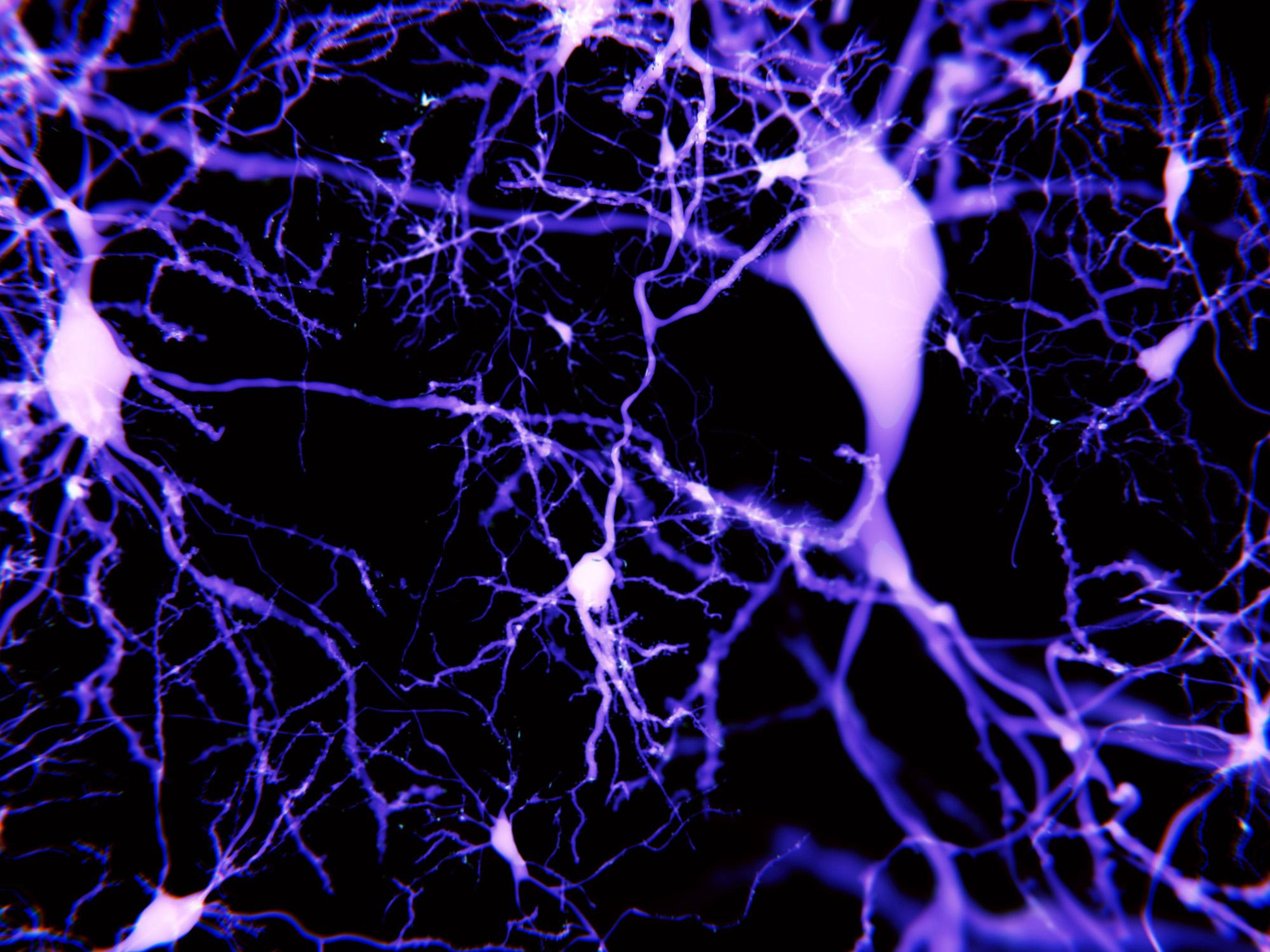

Using nerve cells grown in a dish, the researchers found that beta-amyloid – which causes the brain degeneration in Alzheimer’s – boosts its own production whenever it destroys a brain connection.

This means that drugs created to try and clear up beta-amyloid could effectively be fighting a losing battle.

"We show that a vicious positive feedback loop exists in which beta-amyloid drives its own production," said Dr Richard Killick of King’s College London, who led the research.

"We think that once this feedback loop gets out of control it is too late for drugs which target beta-amyloid to be effective, and this could explain why so many Alzheimer's drug trials have failed."

Overproduction of beta-amyloid results in the destruction of brain connections, or synapses, and so this substance has been a natural target for scientists seeking a cure for this devastating disease.

The researchers also found that a protein called Dkk1 has a central role in the beta-amyloid feedback loop, and may even stimulate its production.

In their research, published in the journal Translational Psychiatry, they suggest that targeting Dkk1 – as an anti-stroke medication called fasudil does – could be a way to overcome Alzheimer’s. In mice, they showed that fasudil is capable of preserving both synapses and memory.

Though researchers cautiously welcomed the findings, Dr Diego Gomez-Nicola, a neuroscientist at the University of Southampton, said further experimental work would be needed before anti-amyloid approaches could be written off completely.

Dr Carol Routledge, director of research at Alzheimer’s Research UK, agreed there was still a lot that remained unknown.

“While this study provides solid evidence about an important molecular mechanism driving damage in Alzheimer’s, it is based on research in cells and mice,” she said.

“Fasudil is an approved drug for other health conditions, but is currently used in a critical care setting and would need to go through robust safety tests in trials of people with Alzheimer’s disease.”

Nevertheless, Dr James Pickett, head of research at the Alzheimer’s Society, said such repurposing of existing drugs “could be a real treasure trove”.

“There haven’t been any new drugs last 15 years, so it’s very promising to have uncovered a reason why some of that research may have failed and a potential solution, which builds on our own previous research into this area,” he said.

“Although only tested on mice in this instance, it is encouraging to see a drug already used in humans, fasudil, has the potential to reduce the build-up of amyloid. At this stage we don’t know if the effect will be the same in humans, so further exploration is needed.”

The findings emerged as another study showed that purging “zombie” cells – which have stopped functioning but haven’t died – from the brain could open up new methods of treating dementia.

That research, published in the journal Nature, was welcomed as “exciting” by Alzheimer’s specialists, although once again they noted that the science was a long way from yielding any results in humans.

“We need to exercise caution as to not over-interpret its relevance to dementia in humans as the study was performed in a mouse model,” said Professor Lawrence Rajendran of Kings College London, who was not involved in the study.

“Nevertheless, this study shows promise for alternative ways to tackle the disease which has been so far difficult using traditional approaches.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments