The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

'Holy grail' blood test for early Alzheimer’s indicators could help patients begin treatment before they show symptoms

The test can detect the early build-up of the defective protein molecules, amyloid beta, in the brain with 90 per cent accuracy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A blood test that could allow accurate and cheap identification of one of the early indicators of Alzheimer’s before the disease begins to cause noticeable symptoms has been developed by scientists.

It is thought this could make earlier treatment to slow or, in future, halt the progression of the disease possible, giving patients more years of symptom-free health and independence.

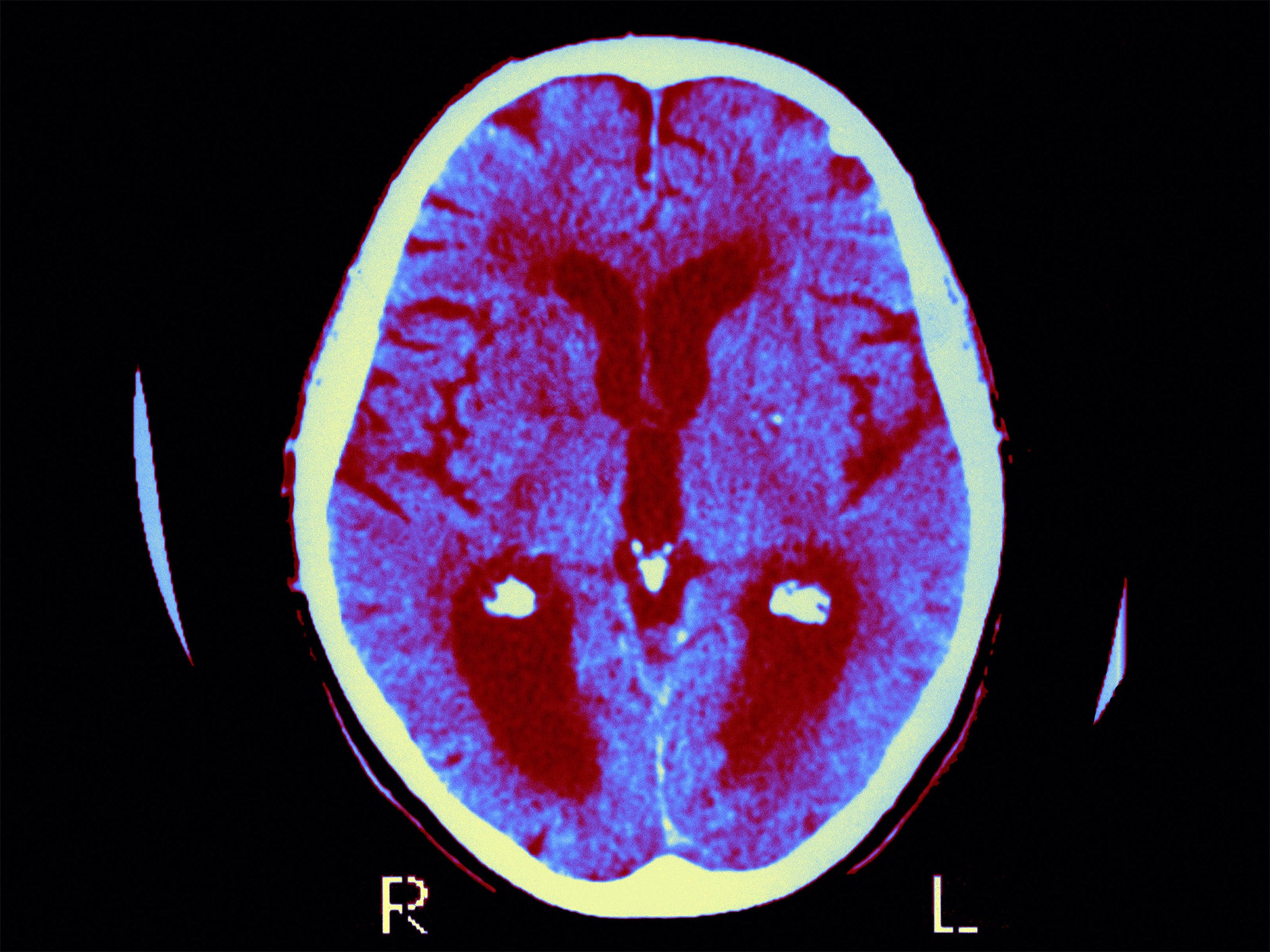

Currently, only expensive and invasive tests can reliably detect the early build-up of amyloid beta, the defective protein molecules in the brain that are a major hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease.

Now researchers from Japan and Australia have for the first time demonstrated that the “precursor” molecules that form amyloid beta protein build-ups can be detected in the blood with 90 per cent accuracy.

Independent researchers said the findings were “very promising” and demonstrated that a blood test – the “holy grail” of Alzheimer’s research – can provide accurate results.

But they nonetheless cautioned that amyloid beta build-up alone does not mean a person is going to develop Alzheimer’s or dementia and the findings need to be validated further in a larger patient population.

However, this test could allow patients to be prioritised for further testing, or as candidates for trials of new drugs, they said.

Writing in the journal Nature, they said that there are two accepted ways to detect the amyloid protein: through a positron emission tomography (PET) scan – which can cost upwards of £1,000 a time – or through a lumbar puncture, a so-called “spinal tap”, to measure build-up in the cerebrospinal fluid.

The researchers trialled the new test in 373 Japanese and Australian patients who were either cognitively normal, had mild impairment or who had diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease.

They then checked the accuracy of their predictions using the accepted PET scan and spinal fluid measurements, and found that the test was right nine times out of 10.

“These results demonstrate the potential clinical utility of plasma biomarkers in predicting brain amyloid beta burden at an individual level,” the researchers, from the National Centre for Geriatrics and Gerontology in Obu, Japan, wrote.

“These plasma biomarkers also have cost-benefit and scalability advantages over current techniques, potentially enabling broader clinical access and efficient population screening.”

Independent researchers agreed. Professor Tara Spires-Jones, the UK Dementia Research Institute programme lead, said this method needed validating in more people and at different stages of the disease.

But she added: “This data is very promising and may be incredibly useful in the future, in particular for choosing which people are suited for clinical trials and for measuring whether amyloid levels are changed by treatments in trials.”

Paul Morgan, professor of immunology and director of the Systems Immunity Research Institute at Cardiff University, said that while the test method described was “technically demanding”, it was likely a better option.

“Easily and cheaply measured blood plasma-derived biomarkers that aid diagnosis, stratification or prediction of outcome in individuals suspected of having early signs of disease represent a ‘Holy Grail’ of Alzheimer’s research,” he said.

“The study clearly shows that PET scanning to assess disease burden, an expensive and invasive procedure, may not be needed in future either for diagnosis or for monitoring response to treatment”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments