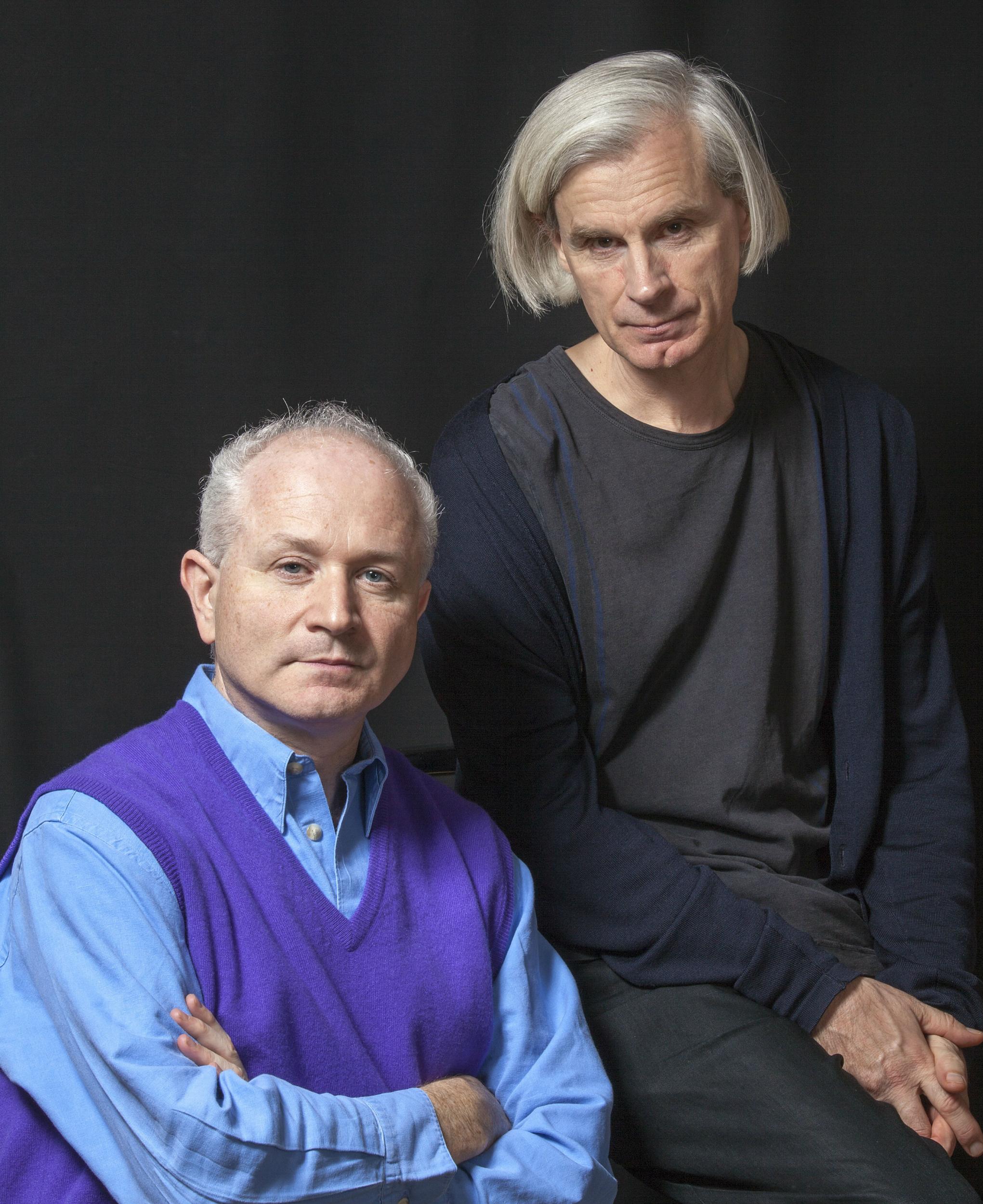

George Benjamin's opera Written on Skin was instantly declared a modern masterpiece – can he follow its success with Lessons in Love and Violence?

The perfectionist composer is again working with director Katie Mitchell and librettist Martin Crimp, to tell the story of Edward II and his lover Gaveston

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When George Benjamin’s opera Written on Skin opened in 2012, it was immediately acclaimed as a masterpiece. One critic suggested that it was one of the defining works of the 21st century.

What made the event even more remarkable was that it was only Benjamin’s second attempt at opera, and his first large-scale work in nearly a decade. For a composer whose painstaking process had become mildly notorious – he took the better part of 10 years to complete a single 15-minute piece, dryly called “Sudden Time” – there was a sense that a dam had burst.

Sitting at his kitchen table in west London, Benjamin still seems a little stunned – not so much by the reaction to the opera as by the fact that he’d been able to compose it at all.

“A piece on that scale, an hour and a half of music – these are things I’d never felt able to attempt before,” he says. “It was a very long wait.”

A barbed fable with a grisly ending about a medieval love affair, filled with savage yet powerfully sensual music, Written on Skin provoked similarly passionate reactions in Aix-en-Provence (the French festival where it originated), London, Amsterdam, New York, Moscow, Toronto, Stockholm – nearly 100 performances in all, remarkable for a contemporary opera.

Six years later, Benjamin and his collaborators are doing it all over again: His new opera, Lessons in Love and Violence, premiered at the Royal Opera House on Thursday; it opens in Amsterdam at the end of June.

Like Written on Skin, the new piece has been created with playwright Martin Crimp and director Katie Mitchell. Like Written on Skin, it invites us to enter a world that seems, at first glance, distant – in Lessons, the 14th-century English court of Edward II, infamous for being deposed, then perhaps murdered, because of his love for a lowborn male favourite.

Yet, also like Written on Skin, while the setting may seem remote, the passions are anything but. Benjamin’s music surges with volatile feeling; in Crimp’s libretto, the relationship between the king and Gaveston, the favourite in question, is both heady and fraught with risk.

Unlike in their previous opera, which placed a tale from the early Middle Ages within a coolly contemporary frame, this time Mitchell has set the action in modern dress, in a European court that might perhaps be in session now. “It’s a modern interpretation of a medieval story,” she says.

Benjamin says he was drawn to the material by the tensions and paradoxes of Edward II’s life. An apparently loving husband, by all accounts close to his children, the king nonetheless found himself drawn into a relationship with a man that, in the words of one medieval chronicler, became a “indissoluble bond of love”.

Whether Gaveston felt the same, or was operating out of calculating self-interest, is one of many questions Lessons in Love and Violence leaves open. Love may be an addictive substance, but it is also shown to be dangerous and ultimately fatal (another echo, perhaps, of Written on Skin, in which a married woman is forced to eat her dead lover’s heart).

“The boy loves his father, Queen Isabel loves her husband, and in some ways the king really does love Isabel, too,” Benjamin says. “The big problem is that the king is intoxicated by Gaveston and cannot escape, despite the fact that it’s tearing his family apart and his kingdom apart. The force of attraction, the force of compulsion, is – as it was in the real story – almost insane.”

Unlike other treatments of Edward’s life – notably Derek Jarman’s 1991 film of Christopher Marlowe’s play Edward II, which turns the story into an impassioned defence of same-sex relationships – he and Crimp had no wish to editorialise. “I don’t like the idea of poster art,” Benjamin says.

Instead, he says, he hoped that its psychological depths and complications would come out: “There’s a lot of ambiguity and emotional complexity.”

Benjamin has long been regarded as one of the most abundantly talented musicians of his generation. Born in London, in 1960, he began composing at the age of seven and studied in Paris with Olivier Messiaen and his wife, Yvonne Loriod, while still a teenager. (Messiaen compared him to Mozart.)

In 1980, at 20, he became the youngest living composer to have a piece performed at the BBC Proms: the astonishingly assured Ringed by the Flat Horizon, which alternates shimmering textures with primitive stabs of sound.

But those early successes were followed by painful years of struggle, sometimes verging on creative paralysis, as he battled to write music that lived up to his fanatically high standards. Critics praised his chamber piece At First Light (1982, inspired by an oil painting by Turner), which conjures the colours of the sunrise with delicate precision – gauzy clouds of strings slowly burnt off by a blazing glare of brass.

More recently, the two-part orchestral work Palimpsests (2002) glittered with the dazzling sonorities that have become Benjamin’s hallmark but also felt consumed by a wild, hungering energy.

There was just one problem: as good as the music was, there wasn’t nearly enough of it. “For a long time, it felt almost like a burden,” says Gillian Moore, a friend of Benjamin’s and the director of music at the Southbank Centre in London. “Everything had to go through this extraordinary process of refinement and moulding. He spent 25 years working incredibly slowly, trying to get everything absolutely perfect.”

One breakthrough was Benjamin’s discovery of electronics in the late 1980s, courtesy of Pierre Boulez’s IRCAM research centre in Paris, which brought about his skitteringly brilliant work Antara (1987), written for digitally sampled Peruvian panpipes and an improbable ensemble of flutes, trombones, strings and two anvils.

Not long afterward, the composer met Indian flutist Hariprasad Chaurasia, travelled to India and Sri Lanka, and became fascinated by the sonic possibilities of South Asian music.

His collaborations with other artists have seemed to release Benjamin’s gifts. Since he was a child, he wanted to write operas. “Probably it was a bit weird,” he says, laughing. But he couldn’t find the right musical language, still less a like-minded librettist.

After more than two decades interviewing writers of all kinds, he had almost abandoned the art form when a colleague suggested he meet Crimp, an experimental playwright whose terse and precise dramas had – so the colleague thought – an affinity with Benjamin’s music.

The hunch proved right: just 16 months after an exploratory meeting, their first opera, a miniaturised retelling of the Pied Piper myth called Into the Little Hill, was onstage in London.

“There’s something about his words that brings music for me,” Benjamin says. “There’s torrential emotion and force and violence, but at the same time this crystalline, bejewelled structure.”

Crimp says: “George’s music has a combination of sensuousness and intellectual rigour; those are the two things that go together. George doesn’t like me saying this because he thinks it’s over-flattering, but that’s something I love about Bach, too.”

Benjamin is quick to point out that he still doesn’t find composing easy. “It’s still sort of impossible,” he says.

Lessons in Love and Violence has taken him just over two and a half years – roughly the same as Written on Skin – and required him to adopt hermit-like solitude, abandoning teaching and performing commitments and barely leaving his house.

He knew exactly how the piece should sound, but he couldn’t wait to hear how his team of performers would transform it.

“That’s the bit I want to discover,” he says.

A few weeks later, during a short break in rehearsals at the Royal Opera House, Benjamin seems tired – being conductor as well as composer is taking its toll, he admits – but also energised by finally putting the whole thing together.

“Opera is a scary medium, but that adds to its beauty,” he says. “It’s not prepackaged; it’s not frozen. It’s performed life, in all its complexity. It can go terribly wrong, but when it goes well, some special communication can happen.” He pauses. “Fingers crossed.”

So there might be more operas from him and Crimp?

“Oh, definitely,” he says. “After this, I wouldn’t want to stop.”

‘Lessons in Love and Violence’ is at the Royal Opera House until 26 May

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments