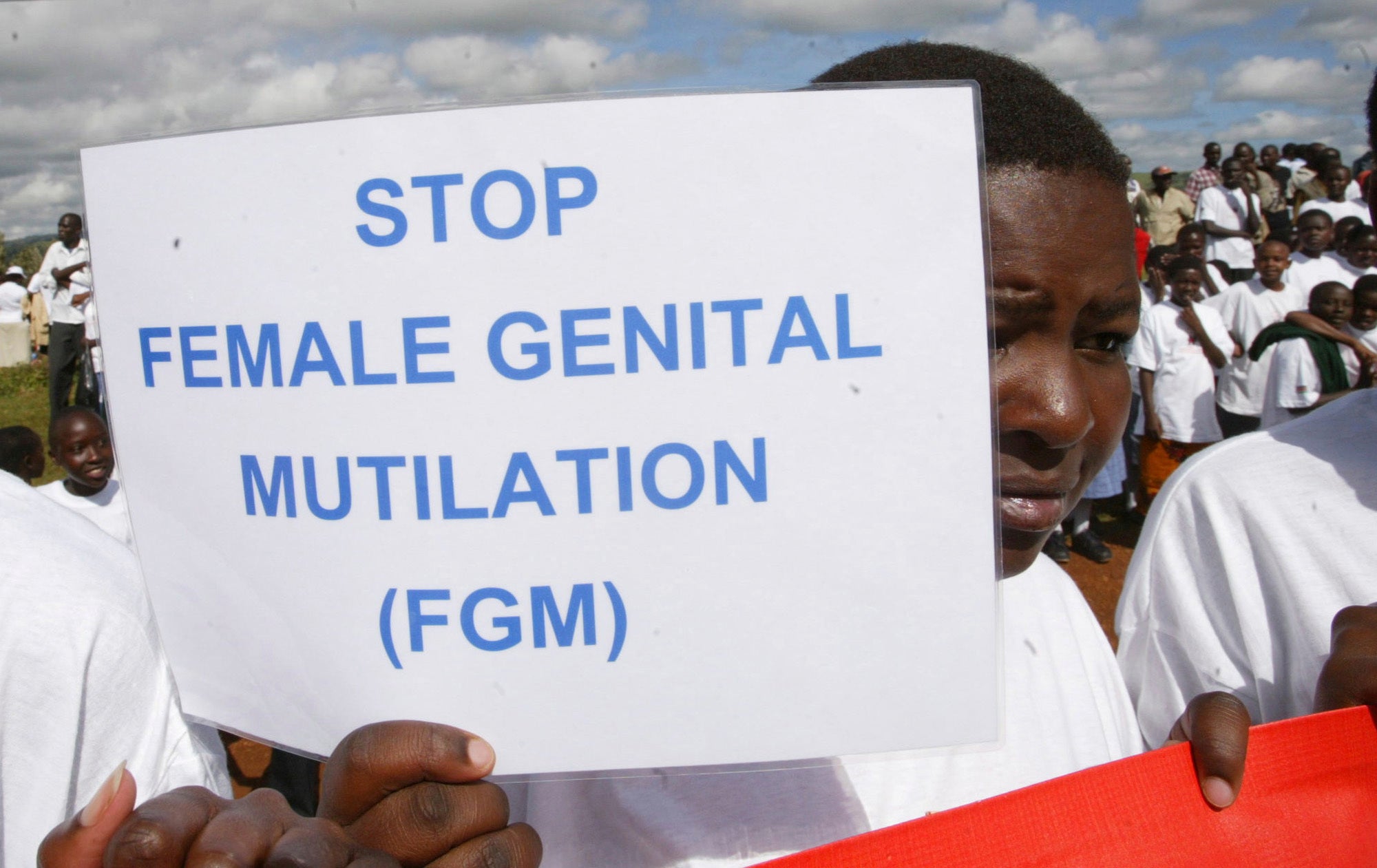

Gambia upholds its ban on female genital cutting. Reversing it would have been a global first

Lawmakers in the West African nation of Gambia have rejected a bill that would have overturned a ban on female genital cutting

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Lawmakers in the West African nation of Gambia on Monday rejected a bill that would have overturned a ban on female genital cutting. The attempt to become the first country in the world to reverse such a ban had been closely followed by activists abroad.

The vote followed months of heated debate in the largely Muslim nation of less than 3 million people. Lawmakers effectively killed the bill by rejecting all its clauses and preventing a final vote.

The procedure, also called female genital mutilation, includes the partial or full removal of girls' external genitalia, often by traditional community practitioners with tools such as razor blades or at times by health workers. It can cause serious bleeding, death and childbirth complications but remains a widespread practice in parts of Africa.

Activists and human rights groups were worried that a reversal of the ban in Gambia would overturn years of work against the centuries-old practice that's often performed on girls younger than 5 and rooted in the concepts of sexual purity and control.

Religious conservatives who led the campaign to reverse the ban argued the practice was “one of the virtues of Islam.”

“It's such a huge sense of relief,” one activist and survivor, Absa Samba, told The Associated Press after the vote. “That is a lot of excitement out here. But I believe this is just the beginning of the work.”

In Gambia, more than half of women and girls ages 15 to 49 have undergone the procedure, according to United Nations estimates. Former leader Yahya Jammeh unexpectedly banned the practice in 2015 without further explanation. But activists say enforcement has been weak and women have continued to be cut, with only two cases prosecuted.

Even now, “it was widespread and there was public promotion of it,” Samba said. She called for more public education about the health consequences of the practice.

UNICEF earlier this year said some 30 million women globally have undergone female genital cutting in the past eight years, most of them in Africa but others in Asia and the Middle East.

More than 80 countries have laws prohibiting the procedure or allowing it to be prosecuted, according to a World Bank study cited earlier this year by the United Nations Population Fund. They include South Africa, Iran, India and Ethiopia.

“No religious text promotes or condones female genital mutilation,” the UNFPA report said, adding there is no benefit to it.

Long term, the practice can lead to urinary tract infections, menstrual problems, pain, decreased sexual satisfaction and childbirth complications as well as depression, low self-esteem and post-traumatic stress disorder.

___

Pronczuk reported from Dakar, Senegal.