Emmanuel Macron: The man who is France's next president

39-year-old former banker has made it to the Élysée Palace

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Emmanuel Macron has done something thought unthinkable just six months ago: becoming President of France without the support of either of the two major political parties.

When the 39-year-old resigned from Socialist President François Hollande’s government in 2016 to launch his En Marche! (On the Move!) political movement many thought he was doomed to failure.

But in just 18 months the movement signed more than 200,000 signed-up members and Mr Macron has now won the French presidential election, beating another political outsider, the Front National's Marine Le Pen, into second place.

This election has been the most shocking and unpredictable in modern French history. Mr Hollande became the first president not to run for a second term since the founding of the Fifth Republic in 1958 and his party’s chosen successor, Benoit Hamon, came in an unprecedented fifth place behind far-left rival Jean-Luc Melenchon in the first round.

Meanwhile the centre-right Républicains had a disastrous campaign after their candidate, former Prime Minister François Fillon, suffered from several scandals including allegations that he used public money to pay his wife for administrative work she does not appear to have done.

Mr Macron making it into the Élysée Palace is a remarkable achievement for a former banker who was plucked from relative obscurity by Mr Hollande to become his economy minister in 2014.

Mr Macron was born into a middle-class family in the northern city of Amiens where he was educated at mostly private Catholic schools.

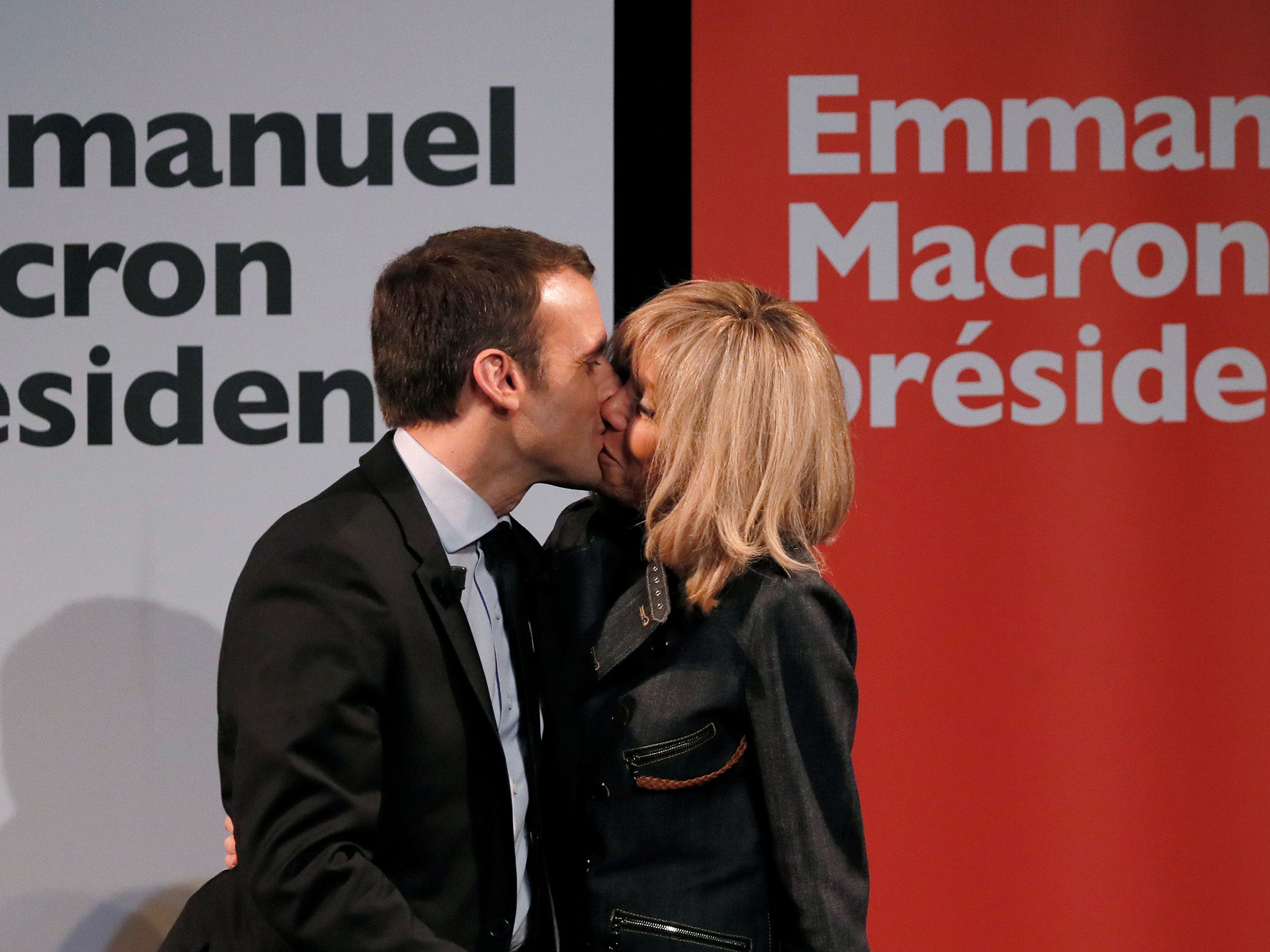

While in high school he fell in love with his drama teacher, Brigitte Trogneux, who was 24 years his senior, when they collaborated on an end of year play. When his parents sent him to finish his final year of school at an elite establishment in Paris, he refused to give up on Ms Trogneux and proclaimed he would come back and marry her.

Sure enough, the couple stayed together and eventually married in 2007. They now live together in Paris with her three children from her first marriage.

Ms Trogneux has played a key role in the election campaign, with Mr Macron vowing that she will have a role in his administration. She has been quoted as saying she is “the president of his fan club” and is often seen attending high-level meetings by his side.

Despite initially wanting to be a novelist, Mr Macron graduated from the elite Sciences Po university in Paris before entering the civil service. He worked at the French treasury for four years before leaving to become a banker. In 2012 he was appointed as Mr Hollande’s deputy chief of staff, then economy minister.

During his tenure in government Mr Macron became particularly unpopular among the traditional left as he enacted a series of labour laws, including one which allows companies to negotiate over the 35-hour week, which led to severe strikes across France.

Mr Macron pitched himself as a socialist-liberal and played on his personal appeal as a young, fresh face and a counterpoint to the xenophobic, nationalistic, anti-globalisation campaign of Ms Le Pen.

Before he announced his candidacy for president his team, inspired by the Obama campaign in the US in 2008, carried out a survey of thousands of French citizens to hear what policies they wanted from their politicians.

Le grande marche (the great walkabout) by supporters and activists resulted in 25,000 unusually in-depth interviews with votes which he has built his policy platform on, the BBC reported.

The resulting centrist manifesto has been ridiculed for being too bland and trying to please everyone but broadly speaking he vows to cut taxes and spending but also provide support for those on low incomes along with €50bn (£42bn) for public infrastructure and a shift to renewable energy.

More controversially he has vowed to cut corporation tax and red tape, allowing companies to renegotiate the 35-hour week and make it easier to hire and fire.

His supporters say this will help revive France’s moribund economy as many believe strict statist rules. The French labour code is famously longer than the Bible, deterring investment and private sector growth.

Mr Macron has vowed to bring unemployment down from its current 10 per cent to 7 per cent. His biggest challenge is winning over blue collar workers who are put off by his support for globalisation, multiculturalism and the EU.

Some dissatisfied voters see immigration as the source of their woes and have flocked to the Front National, which is vowing to “bring back French sovereignty” with a referendum on EU membership; the suspension of immigration; and to fight back against perceived Islamist extremism in civil society.

During a presidential debate last month, Ms Le Pen attacked Mr Macron for his vague policy positions saying he managed to speak about foreign policy for seven minutes without saying anything at all.

“I know the divisions in our nation, which led some to vote for extremist parties. I respect them,” Mr Macron said in a solemn address at his campaign headquarters after winning the presidency.

“I will work to recreate the link between Europe and its peoples, between Europe and citizens,” he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments