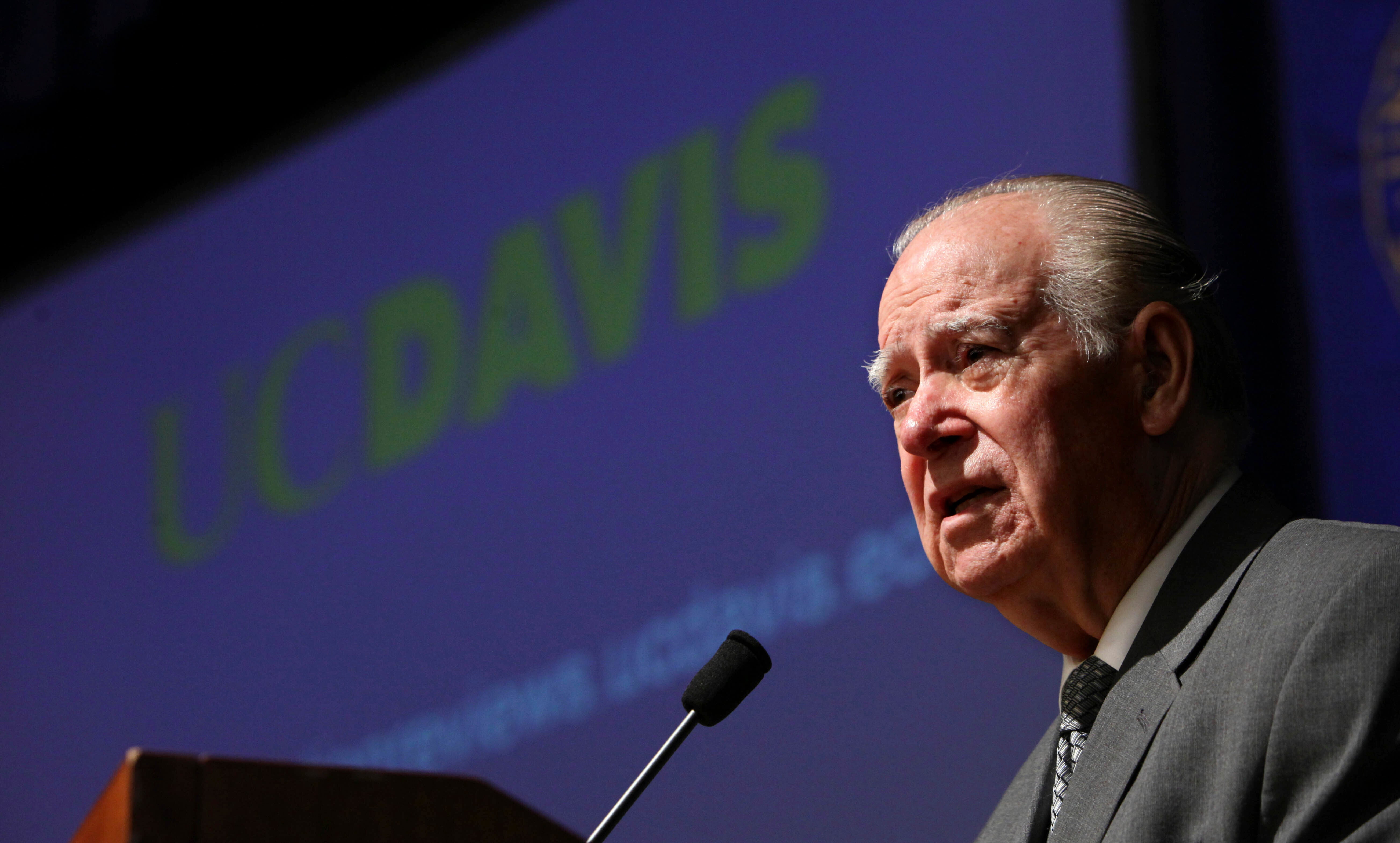

First Latino justice on California's high court dies at 90

Cruz Reynoso, a son of migrant workers who worked in the fields as a child and went on to become the first Latino state Supreme Court justice in California history, has died

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Cruz Reynoso, a son of migrant workers who worked in the fields as a child and went on to become the first Latino state Supreme Court justice in California history, has died. He was 90.

Reynoso died Friday at an elder care facility in Oroville, according to his son Rondall Reynoso. The cause of death was not disclosed.

In a legal career that spanned six decades, Reynoso played a prominent role in the movement to uplift the poorest workers in California, especially farmworkers from Mexico like his parents, and guided many minority students toward the law.

As director of California Rural Legal Assistance — the first statewide, federally funded legal aid program in the country — in the late 1960s he led efforts to ensure farmworkers' access to sanitation facilities in the fields and to ban the use of the carcinogenic pesticide DDT.

One of the biggest cases won by CRLA while Reynoso was its director centered on Spanish-speaking students who were incorrectly assessed by their schools and placed into classes for the mentally challenged when, in reality, they were simply new English learners. The 1970 class-action lawsuit filed on behalf of Latino students in the Monterey County town of Soledad ended the practice of giving Spanish-speaking students IQ tests in English.

After leaving CRLA in 1972, Reynoso taught law before he was appointed to the state’s 3rd District Appellate Court in Sacramento. In 1982, Gov. Jerry Brown appointed Reynoso to the state Supreme Court, the first Latino to be named to the state’s high court.

He earned respect for his compassion during his five years on the state Supreme Court but became the target of a recall campaign led by proponents of the death penalty who painted him, Chief Justice Rose Bird, and Associate Justice Joseph Grodin as being soft on crime. The three were removed in 1987.

After leaving the bench, he practiced and taught law at the University of California in Los Angeles and in Davis and served on the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights and the United Nations Commission on Human Rights. He received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Bill Clinton in 2000.

“Cruz Reynoso was a giant for the judiciary and the legal profession in California and across the country,” Mariano-Florentino Cuellar, a justice on the California Supreme Court, said in a statement.

“His accomplishments were as remarkable as his humility. His memory and deeds will continue to inspire so many of us across California and the rest of our country.”

Born in Brea on May 2, 1931, Reynoso was one of 11 children and spent summers with his family working the fields of the San Joaquin Valley.

After graduating from Pomona College in 1953, he served two years in the Army before attending law school at UC Berkeley.

He was married to Jeannene Reynoso for 52 years until her death in 2007. He married his second wife, Elaine Reynoso, in 2008. She died in 2017.

He is survived by four children and two stepchildren.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.