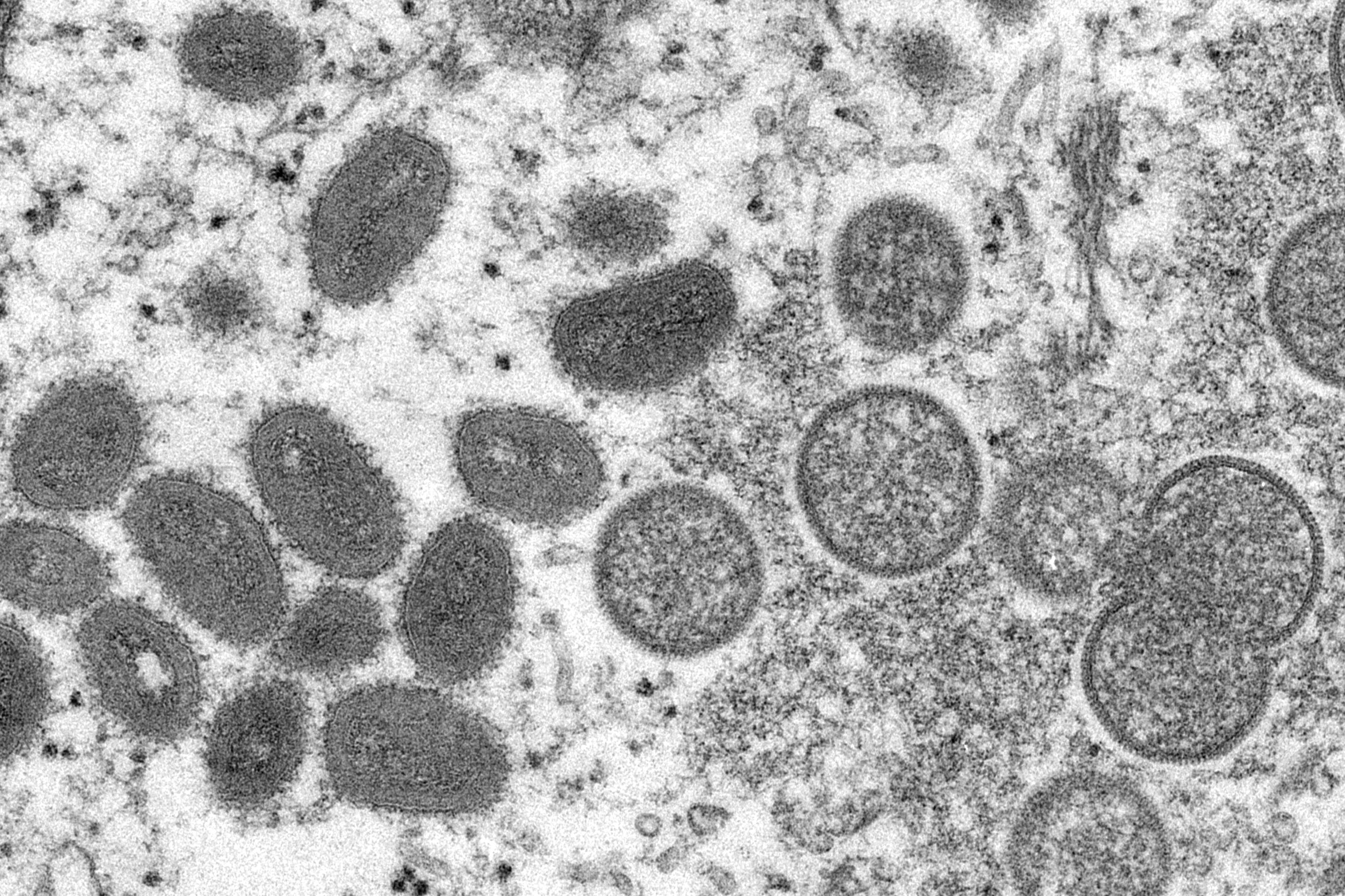

Monkeypox spreads in West, baffling African scientists

As more cases of monkeypox are detected in Europe and North America, scientists who have monitored numerous outbreaks in Africa say they are baffled by the unusual disease's spread in the West

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As more cases of monkeypox are detected in Europe and North America, some scientists who have monitored numerous outbreaks in Africa say they are baffled by the unusual disease's spread in the West.

Cases of the smallpox-related disease haven’t previously been seen among people with no links to central and West Africa. But in the past week, Britain, Spain, Portugal, Italy, U.S., Sweden and Canada all reported infections, mostly in young men who hadn’t previously traveled to Africa.

France, Germany, Belgium and Australia confirmed their first cases of monkeypox on Friday.

“I’m stunned by this. Every day I wake up and there are more countries infected,” said Oyewale Tomori, a virologist who formerly headed the Nigerian Academy of Science and who sits on several World Health Organization advisory boards.

“This is not the kind of spread we’ve seen in West Africa, so there may be something new happening in the West,” he said.

One of the theories British health officials are exploring is whether the disease is being sexually transmitted. Health officials have asked doctors and nurses to be on alert for potential cases, but said the risk to the general population is low.

Outbreaks in Nigeria, which reports about 3,000 monkeypox cases a year, are usually in rural areas, where people have close contact with infected rats and squirrels, according to Tomori. He said the disease is not spread very easily and that many cases are likely missed.

“Unless the person ends up in an advanced health centre, they don’t attract the attention of the surveillance system,” he said.

Tomori hoped the appearance of monkeypox cases across Europe and other Western countries would further scientific understanding of the disease.

The World Health Organization’s lead on emergency response, Dr. Ibrahima Soce Fall, acknowledged this week that there were still “so many unknowns in terms of the dynamics of transmission, the clinical features (and) the epidemiology.”

British officials have so far reported nine cases of monkeypox, noting that the most recent cases have all been in young men who had no history of travel to Africa and were gay, bisexual, or had sex with men.

Authorities in Spain and Portugal also said their cases were in young men who mostly had sex with other men and said those cases were picked up when the men turned up with lesions at sexual health clinics.

Experts have stressed they do not know if the disease is being spread through sex, or other close contact related to sex.

“This is not something we’ve seen in Nigeria,” virologist Tomori said. He said viruses that hadn’t initially been known to transmit via sex, like Ebola, were later proven to do so after bigger epidemics showed different patterns of spread.

The same could be true of monkeypox, Tomori said. “We would have to go back through our records to see if this might have happened, like between a husband and wife,” he said.

In Germany, Health Minister Karl Lauterbach said the government was confident the outbreak could be contained. He said the virus was being sequenced to see if there were any genetic changes that might have made it more infectious.

Scientists said that while it's possible the outbreak's first patient caught the disease while in Africa, what's happening now is exceptional.

“We've never seen anything like what's happening in Europe,” Christian Happi, director of the African Centre of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases, said. “We haven't seen anything to say that the transmission patterns of monkeypox have been changing in Africa, so if something different is happening in Europe, then Europe needs to investigate that.”

Happi also pointed out that the suspension of smallpox vaccination campaigns after the disease was eradicated in 1980 might inadvertently be helping monkeypox spread. Smallpox vaccines also protect against monkeypox, but mass immunization was stopped decades ago.

“Aside from people in west and Central Africa who may have some immunity to monkeypox from past exposure, not having any smallpox vaccination means nobody has any kind of immunity to monkeypox,” Happi said.

Shabir Mahdi, a professor of vaccinology at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, said a detailed investigation of the outbreak in Europe, including determining who the first patients were, was now critical.

“We need to really understand how this first started and why the virus is now gaining traction,” he said. “In Africa, there have been very controlled and infrequent outbreaks of monkeypox. If that's now changing, we really need to understand why.”

___

Geir Moulson in Berlin and John Leicester in Paris contributed to this report.