‘We have a problem’: How ‘untouchable’ criminal kingpins were taken down through secretive phone network

‘We can no longer guarantee the security of your device,’ read panicked message sent out to 60,000 users around the globe. reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On 13 June, 60,000 criminals involved in high-level networks around the world received a message.

“Today, we had our domain seized illegally by government entities,” it read. “We can no longer guarantee the security of your device … you are advised to power off and physically dispose of your device immediately.”

But it was too late. The network had already been corrupted for months, and law enforcement agencies across Europe had been gathering intelligence of a quality never seen before.

They struck in a multitude of raids, seizing tonnes of drugs, millions of pounds in cash and weapons including assault rifles, submachine guns and grenades.

More than 700 suspects – including previously “untouchable” kingpins – have been arrested in the UK alone, where every police force in the country was secretly working on the operation.

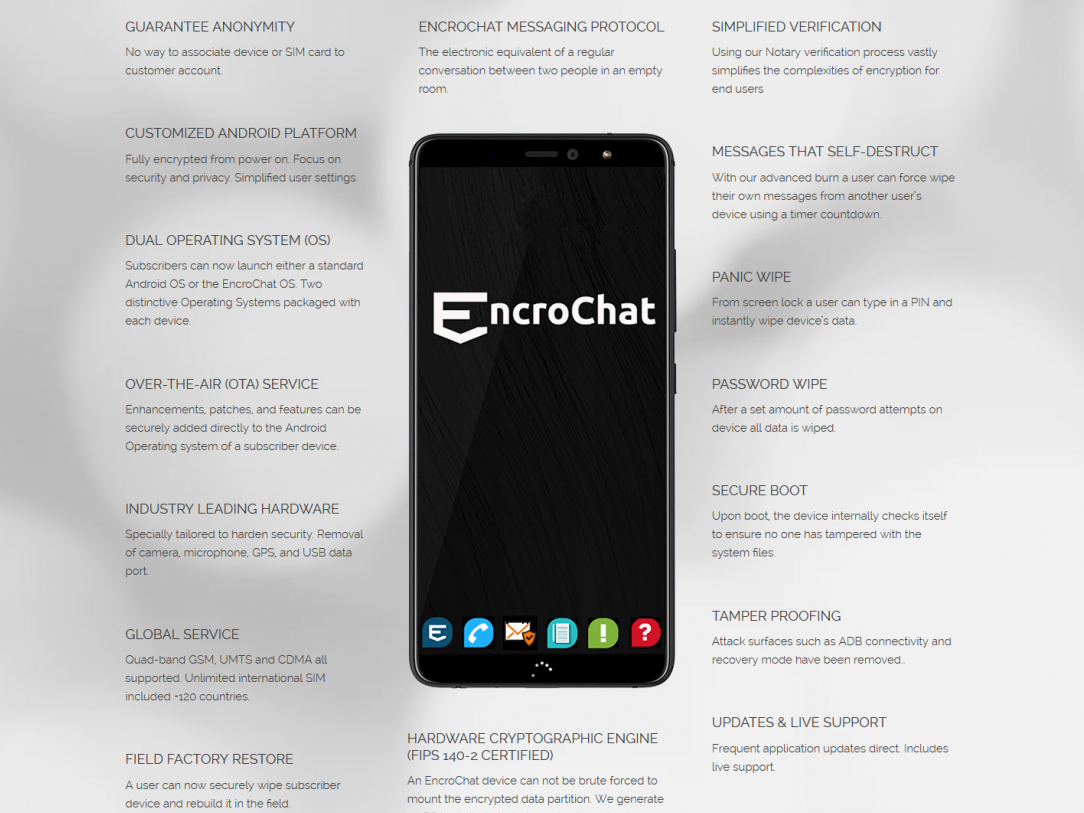

The devices were “EncroPhones” – bespoke mobiles that claimed to offer complete anonymity with a built-in secure operating system, encrypted messaging and calls, self-destructing texts and even a “panic wipe” function.

The product, priced at £1,500 for a six-month contract, attracted organised crime groups across Europe.

EncroPhones became more popular from 2017 onwards following the takedown of the rival Blackberry PGP network.

Human traffickers, drug smugglers, gun importers and money launderers came to rely on the devices, believing they were safe from law enforcement.

But in April, everything changed. International teams including the UK’s National Crime Agency (NCA) were able to “penetrate” the network, accessing the names, details, locations and secrets that gangs had paid so much money to shield from them.

“They believed their conversations were not reachable by law enforcement, so you can imagine the quality of intelligence we’re receiving,” said chief constable Peter Goodman, the National Police Chiefs’ Council lead for serious and organised crime.

Of the estimated 60,000 people using the EncroChat messaging network globally, 10,000 were in the UK.

The NCA assessed that the network was used “completely for criminal purposes” because of the handsets’ design to “frustrate law enforcement ability to gain evidence and intelligence”.

But after they found a way in, the tables turned. In the UK alone, 200 NCA officers worked on the operation every day to identify users and their activities.

It triggered a series of police raids across the country, seeing hundreds of suspected organised criminals arrested including wanted fugitives and “high-value targets”.

The operation also revealed the identities of an unknown number of corrupt police officers and employees in different law enforcement agencies.

Officials said that while police operations against gangs frequently see lower-level operatives who “get their hands dirty” arrested, while those at the top remain free, EncroPhones were only used by the “middle tier upwards”.

Matt Horne, deputy director of the NCA, said: “We are identifying individuals who have been of interest to law enforcement for many years, including fugitives – the ‘Mr and Mrs Bigs’.”

Mr Goodman said those caught as a result of the operation included “iconic figures people have seen benefiting from crime for a number of years”.

“They have managed to distance themselves from criminal activity through devices like this,” he added.

“When we understand the full extent of this compromise, no doubt there will be iconic figures who have not previously been touched by law enforcement who will be going to prison and losing significant assets.”

As a result of the intelligence, attempted assassinations have been thwarted as well as money laundering operations and the importation of guns, drugs and people.

For more than two months, criminals carried on their business unaware that anything was amiss, but after EncroPhone managers sent out the 12 June warning, efforts to destroy the evidence started.

Nikki Holland, the NCA director of investigations, said the message led to an “acceleration of activity”.

“Always planned for the eventuality of them finding out and letting their users know,” she added.

“The more police activity that took place, the more they would become aware.”

Ms Holland said the timing of the operation during the coronavirus pandemic was a coincidence, but that it had “worked to our advantage because more criminals were at home when we came calling” and police had greater capacity because of a drop in crime.

Messages between British users that were intercepted after the alert went out included one reading: “The police are having a field day.”

“If NCA then we have a big problem,” another added.

Officials said that UK-based organised crime groups (OCGs) used EncroChat to import drugs, weapons and people, as well as coordinating “criminal enforcement”.

The network was used for enforcing drug debt, fighting turf wars over competing markets making threats and planning attacks or even assassinations.

An EncroChat-enabled phone was previously used by a hitman who murdered Liverpool gangster John Kinsella in May 2018.

The career criminal was executed by a masked cyclist while walking his dogs, after the gunman was alerted to his location by an EncroChat message.

Mr Horne described it as a “command and control” platform.

“It was a pivotal platform for OCGs to carry out coordination, command and control of that activity,” he added.

“What we see is that it actually is a requirement to do criminal business to have one of these devices, because if you want to work with the supply chain having one of these devices is often the only method of communication.”

Mr Horne said EncroPhones had been “of interest to UK law enforcement for some time” but had been created abroad.

“We are aware the people behind it live a luxurious lifestyle,” he added, saying the attack on the devices had sparked the “largest-ever disruptive impact against OCGs involved at a high level in drugs, firearms and money laundering”.

“It hits right at the heart of the most dangerous OCs operating in our country.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments