Why Mandarin teachers have the remote control

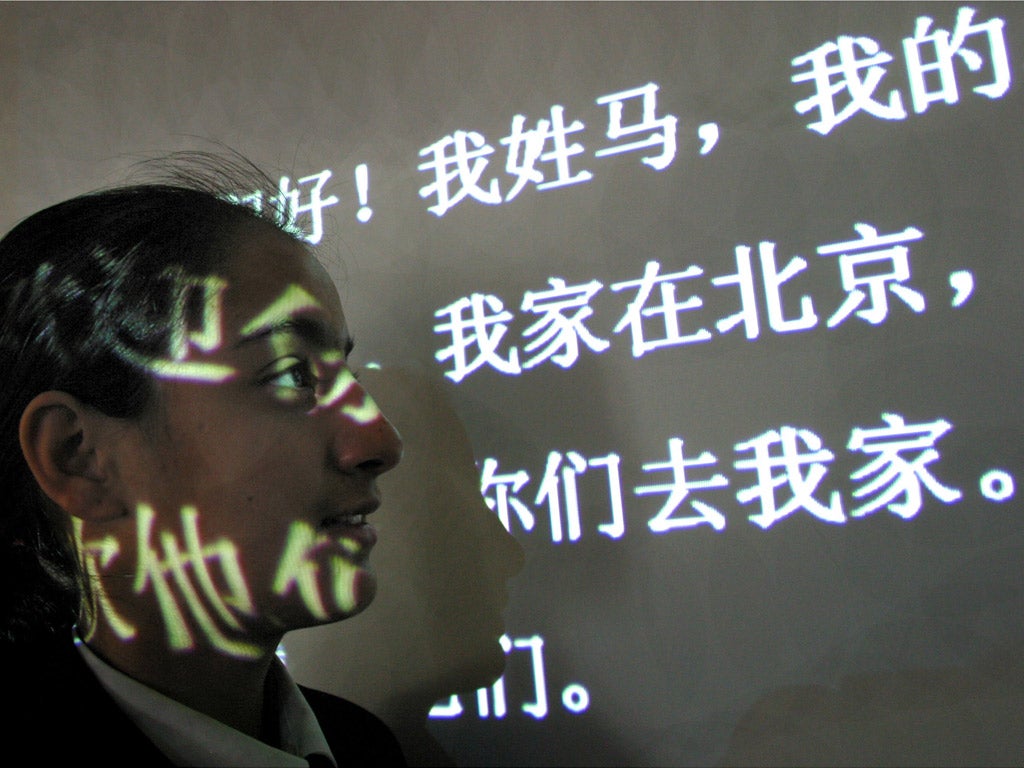

Pupils increasingly want to learn Mandarin – but the UK has only 100 people qualified to teach the language. Jeremy Sutcliffe visits a schools that's found a novel solution: lessons by video conferencing.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Oliver Piggott is not the sort of student you would expect to sign up for a crash course in Mandarin Chinese. Having opted to take chemistry, biology, physics, maths and computer science A-levels, he hopes to study a combination of science and technology at university in preparation for a career in industry.

The 16-year-old is about to start his A-levels in the sixth form at Woldgate College in Pocklington, a picturesque market town nestled at the edge of the Yorkshire Wolds. He is one of a group of students considering taking a two hours-a-week course in Mandarin as part of the school's enrichment programme. The aim is to give students the chance to learn the language spoken in the world's fastest-growing economy.

For Oliver, who like many of his generation dropped languages at 14 after the Labour government ended the requirement for pupils to study a language to 16, the idea of learning Mandarin makes perfect sense. "I've seen Mandarin come up in the news and it seems to me like quite a good skill to have if you want to go around the world," he says. "It's an up and coming language and I think it's a good idea to be able to work with people in China and to speak their language. It appeals to me on a business level. If you want to be successful, you have got to be able to adapt to the places that are up and coming. Learning Mandarin is a good start."

This argument perfectly sums up the national debate about modern languages in schools. With China predicted to overtake the United States as the world's largest economy by 2027, successive government ministers have spoken of the need to establish Mandarin as a mainstream subject.

In January 2010, Labour education secretary Ed Balls said he wanted every secondary school pupil to have the right to learn an "up and coming" languages such as Mandarin, Japanese or Arabic. His successor Michael Gove announced a five-year programme to train 1,000 extra Mandarin teachers for England's secondary schools.

Gove's bold statement looked set to dramatically increase the number of pupils learning Mandarin from Year 7 onwards. The move was necessary, he said, to equip the next generation with the skills needed to ensure the long-term success of the UK economy.

But despite these ambitions, the stark reality is that very few schools have the capacity to teach Mandarin. When Gove made his announcement there were just 100 qualified Mandarin teachers in the UK. The most recent Language Trends survey by CfBT Education Trust shows that, while the proportion of state secondary schools offering Mandarin rose from 9 per cent to 16 per cent between 2007 and 2009, it fell back to 14 per cent in 2011.

Moreover, while this still means that around 500 schools offer Mandarin, the reality is that only a minority teach it as a GCSE or A-level subject and most of those are in the independent sector. The majority offer it as a short "taster" course, often after school.

One reason is that qualified Mandarin teachers are like gold dust, says Rachel Cope, head of modern languages at Woldgate College. "I tried to put Mandarin on the curriculum last year in the sixth form and I really struggled to find a teacher because there simply aren't enough. At the moment it isn't appearing in any schools in the East Riding, which is a shame because we are all keen to take new languages on board. But for now the languages taught in schools remain very much the European languages, French, Spanish and German."

Woldgate's answer is to offer its sixth formers Mandarin lessons via video-conference link, offering Oliver and his fellow students the chance to be taught by an experienced Mandarin tutor.

The course is run by MB Learning Solutions, a Conwy-based firm that provides A-level, GCSE and taster courses to schools unable to supply in-house teachers in specific subjects. The company is the first in the UK to offer schools GCSE and enrichment courses in Mandarin via distance learning.

Video conferencing, which provides a two-way visual link between a class of students and their tutor, has enabled Woldgate to offer a number of additional subjects they would not otherwise be able to provide, including GCSE Latin in Year 10 and electronics and law at A-level.

"This course is a really innovative answer to our problem of not being able to find a qualified Mandarin teacher," says school principal Jeff Bower. "It gives our students an introduction to the language and shows their interest and commitment to learning something different that will stand them in good stead when they apply to university.

"This is a first step for us but we hope to expand Mandarin courses lower down the school in future. I know of schools that are considering introducing Mandarin as a language from Year 7, instead of French or Spanish. The problem they are having is staffing. Video conferencing is an effective alternative."

Course tutor Joseph Buck, 27, a fluent Mandarin teacher, says that by the end of the one-year AQA short course in speaking and listening, students will be able to communicate in Mandarin on day-to-day topics with confidence. They will also learn about Chinese culture.

He says: "They will come away with a genuinely practical skill they are capable of using straight away. I teach a lot of adults, many of them international buyers who regularly visit China and who are looking to gain a better understanding of Chinese culture. Just being able to say a few words in Mandarin to a Chinese person gets you a long way."

The person tasked with delivering Michael Gove's pledge to train 1,000 Mandarin is Katharine Carruthers, director of the Confucius Institute at London University's Institute of Education. She is adamant that the target will be met.

About 30 teachers a year will be produced through mainstream training routes such as the PGCE and Graduate Teacher Programme, she says. The institute is also running a 30-hour course in classroom management skills for teachers visiting from China, to give them a taste of teaching in British schools, a very different experience from what they are used to. So far, 178 Chinese teachers have taken the course, while 48 British language teachers have offered the chance to take a crash course in Mandarin in Beijing.

But while all these teachers will receive a qualification, only around 150 are set to become fully qualified Mandarin teachers able to teach to GCSE and beyond. Most will gain only basic qualifications. "What we need is a proper strategy over a number of years to build capacity to teach children properly," says Teresa Tinsley, co-author of the CfBT Language Trends report and an expert in Mandarin teaching. "At the moment there are all sorts of excellent initiatives, some in primary, some in lower secondary and some at sixth form level. Are we going to start in primary and build it up through the system or is it best to offer Chinese to pupils who have already been successful at learning another language?

"At the moment we are spreading our resources too thinly and too often a school gets a teacher in and then they leave and all that good practice is lost. The reality is we cannot assume we are going to teach Chinese in the same way as European languages. The answer may be in very innovative solutions such as distance learning and blended learning by video link."

Jeff Bower is happy to be a pioneer in this experiment: "Video conferencing is the only option for schools like ours. The principle of starting Mandarin in Year 7 or even primary school is terrific but you can't just announce a policy and expect it to happen. We have to look at alternatives and that's what we have done."

Chinese whispers: Mandarin facts

One in four employers rate Mandarin as an essential skill for today's young people, placing it fourth behind German, French and Spanish (CBI/Pearson report 2012)

China is predicted to overtake the United States as the world's largest economy by 2027

There are only about 100 qualified Mandarin teachers in the UK

Mandarin is offered by one in seven state schools but by more than a third of independent schools

It ranks alongside Latin as the fifth most common language offered in state schools after French, Spanish, German and Italian

Almost two-thirds of Mandarin lessons are offered as "taster" courses outside the regular school curriculum

Entries for GCSE Chinese fell by 35 per cent to 2,417 in 2010 after changes in the way the exam was assessed

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments