Network of career colleges will directly help prepare students for the world of work

Richard Garner visits Oldham College, where the innovative courses, with input from local employers, are already up and running

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When injury forced postman Gareth Perry to look for something new, it was an interest outside of work that came to his rescue. "I'd always been interested in video games," the 28-year-old says, "then I heard about this course and decided to sign on."

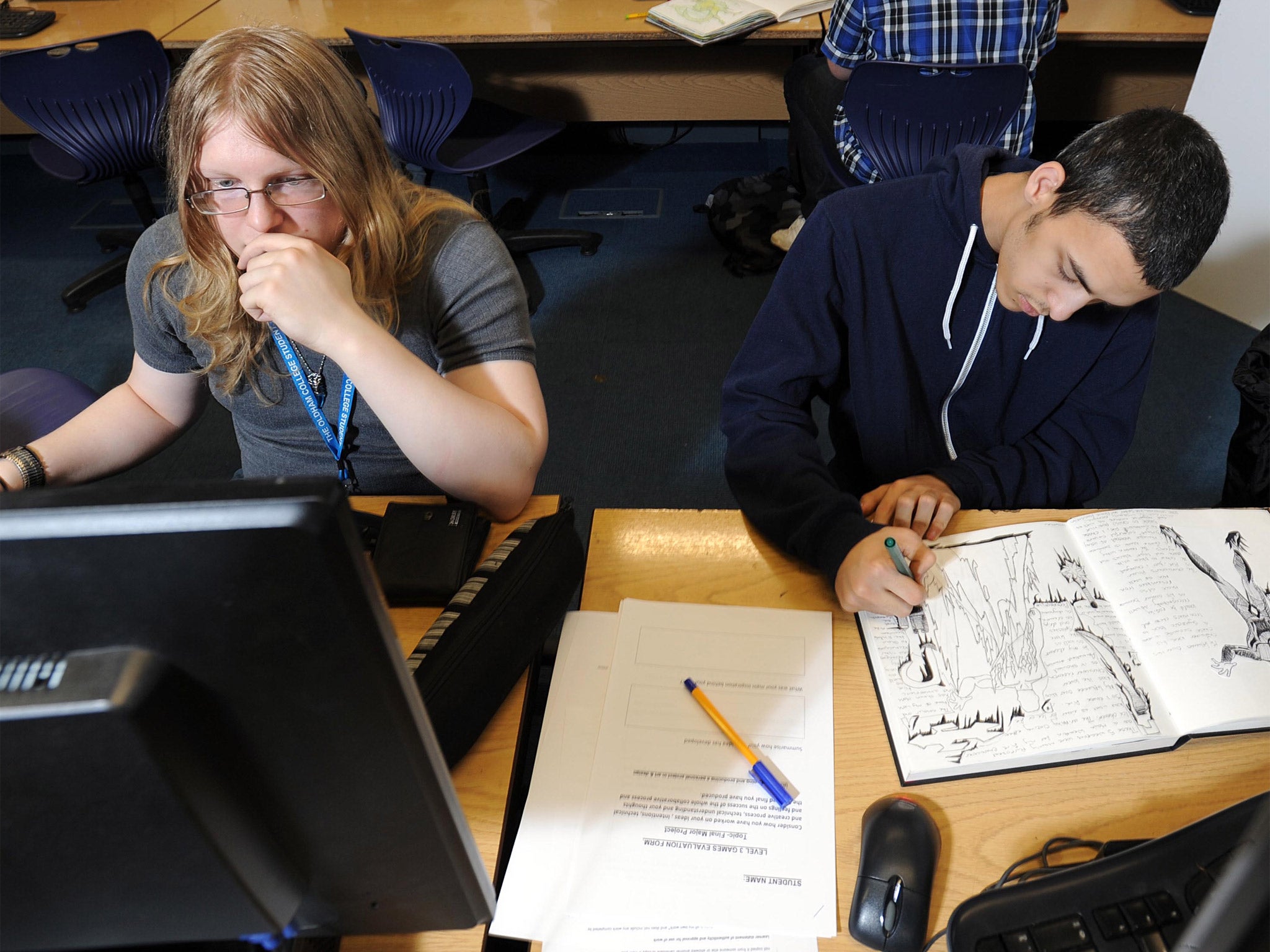

He's now on a course that teaches students how to design their own games at Oldham College in Greater Manchester – and is loving it. "You really learn so much here," he says. "It was more than the right decision."

A fellow mature student is would-be fantasy author Christopher Whittaker, 26, who, in between writing his book, has added to his skills by enlisting for the course.

Oldham College is at the forefront of a movement to create a network of career colleges around the country. The aim of them is to ensure students get the guidance and opportunities to develop the kind of skills they will need for the jobs on offer once they leave college.

The course at Oldham will transfer to new buildings on the site next January, which will house the UK's first career college – a concept first announced last year by former Education Secretary Lord (Kenneth) Baker in The Independent.

The idea behind career colleges was that students could combine academic studies with vocational courses that will help prepare them for the world of work. Each college will have its own specialism.

In Oldham's case, it is preparing students for a creative or digital career – the brainchild of the college's principal, Alun Francis, who says: "We started to think of the idea of the career college approach when working with our partners in a new University Technical College [UTC] on the site."

The UTC – for 14- to 19-year-olds – was putting in a great deal of effort to prepare students for a career in engineering. College leavers are likely to opt for apprenticeships or university courses once they complete their studies.

"We decided we didn't want to compete with that," says Francis, "but that whole approach – the UTC combines academic and vocational learning in a different way to that of schools and colleges – should work with a further education college."

The creative and digital industry seemed an ideal specialism to adopt – jobs in that field are mushrooming in Greater Manchester, particularly as a result of the creation of Media City in Salford, where the BBC has decamped to produce its programmes.

There is also the Sharp Project in nearby Newton Heath, a Manchester City council-sponsored scheme that houses a range of entrepreneurs and production companies involved in the production and dissemination of digital material.

"Sky had made television programmes there," says Francis. It also offers the opportunity to get involved with forensic-science research for the police investigating the misuse of mobile phones. The two industries are expected to generate around 23,000 jobs in the Greater Manchester area within the next decade.

The students on the gaming course will all be transferring to the career-college building in January and should find that life is a little different, not to say more businesslike . "It will be more like a workplace," says Dermot Allen, the college's curriculum leader. "There will be no walls and it will be more open-plan. I won't be able to shout at them."

Francis says of the initiative: "The close involvement of employers will ensure that the curriculum is relevant to the labour market, and students will acquire the specialist skills and knowledge they will need to secure employment or set up their own businesses."

While the actual qualifications on offer may not change that much, the content of the courses, and the approach adopted in teaching them, will. For instance, on a BTEC level-three course in digital technology, there is a maths for computing component which, at present, is largely ignored by those taking the course. "The offer of the component is not often taken up," says Francis, "but it is absolutely essential to a student's employment."

In future, all students will take this component – thus removing the need for some businesses to set up remedial courses, to ensure employees are ready for the demands the jobs make upon them.

Making such a commitment is the sort of issue that can only emerge as a result of having a very close working relationship with employers over the design and content of the courses.

The college at present has 2,600 16- to 18-year-old students, plus a further 7,000 on work-based learning courses. It also runs its own higher-education institution (University College Oldham).

Space on the campus is also being allocated to a new primary school, which in future will allow students to complete their education on just the one site – a move that is seen by education experts as promoting continuity of learning and a way of ridding students of the dread that occurs when they transfer from one sector of education to another.

The opening of the career college will also, it's hoped, attract more students and enhance the college's reputation for encouraging, in particular, students from disadvantaged backgrounds to pursue more profitable careers.

Alun Francis hopes that, eventually, the career college approach adopted for creativity and digital courses will be extended to the rest of the college's provision so that, for instance, students studying health and social care can be housed in one building, with the college working closely with their potential employers on the content of their courses.

Details of the first career colleges were announced yesterday, with two planned to open this year – Oldham and Hugh Baird in Liverpool. The Liverpool college will specialise in preparing students for what it terms "the visitor economy", ie, tourism. It will focus on training young people for the hospitality and catering industries.

A further seven colleges – including Birmingham Metropolitan College and the City of Oxford College – are pencilled in for opening in September 2015.

The Career Colleges Trust expects there will be about 40 career colleges operating around the country within four years – although Ruth Gilbert, the chief executive of the Career Colleges Trust, says that it was not setting targets for the number of colleges. Instead, it wants to see the movement offering places for 25,000 students within four years. "This will create a big dent in the figure of a million unemployed young people," she says.

Luke Johnson, the chairman of the Career Colleges Trust, adds: "The colleges that we have approved today represent very different industries. Not only does this indicate the diverse nature of our new innovative educational concept but it highlights the differing employer and industry needs in various areas.

"This project has come a long way in a short amount of time."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments