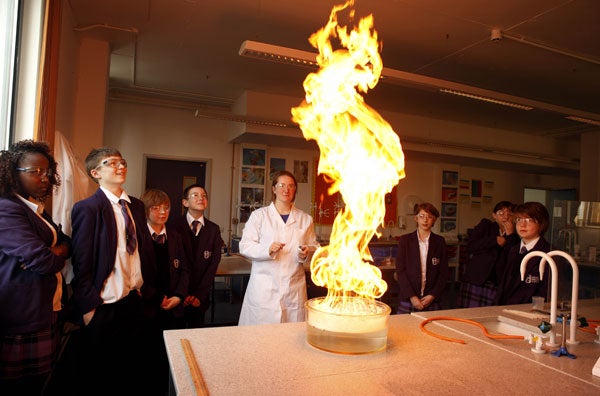

Bang goes science: Why experiments have become a thing of the past

Science is brought alive by practical work but increasingly teenagers do precious little of it.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.You can sense the air of expectation in Vicky Pooley's science classroom at Oriel High School, a mixed comprehensive in Crawley, as she pops a jelly bean into a test tube full of molten potassium chlorate.

The crowd of 11 and 12-year-old pupils surrounding the laboratory bench, has been told to wait for a mini-explosion in the test tube. And sure enough, seconds later, it happens. A surge of white smoke and splodge shoots out of the tube and splatters into the protective glass screen.

"That's what happens inside you when you eat a jelly bean," Pooley explains, underlining the scientific concept she's just demonstrated: the energy stored in the food we eat. "I try to do as much practical work as I possibly can," says Pooley, who has been teaching for six years, "and we have a departmental culture where we support each other in running practicals."

The watching pupils, reacting to the spectacle as they would at a firework display, also seem to grasp the educational value in seeing, and doing, experiments. "It's a lot more fun and you learn more when you do and see stuff yourself," enthuses Katie Tyson, 11.

But a survey out last week suggests that exciting experiences like these are becoming less frequent in schools. Ninety-six per cent of science teachers and laboratory technicians responding to an online questionnaire, run by the nationwide network of Science Learning Centres, said they were in some way hindered from doing practical work. Two-thirds said this was because the curriculum was too crowded. Bad behaviour in classrooms was mentioned as a factor by 29 per cent of teachers, and health and safety fears by 10 per cent.

The survey was co-sponsored by the Association for Science Education (ASE), which represents thousands of school science teachers. "The amount of time devoted to practical work at GCSE has gone down, which we think is quite worrying," says Marianne Cutler, one of the ASE's executive directors and a former secondary science teacher. "And in the sixth form, time devoted to experiments slips even further."

Cutler agrees that a bulging curriculum is the chief culprit, a conclusion that resonates with teachers at Oriel school. "The pressure is on us in the two GCSE years because of the amount of content that we have to deliver," says Helen Everitt, science teacher and deputy head. "So sometimes we can't afford the lesson time to do an experiment, which is a great shame."

Jane Huthwaite, deputy head of science at Twyford Church of England High School in West London, also finds the size of the curriculum a constraint, as well as the general pressure on teachers' time. "It very difficult for us to find the time to sit down and look for suitable experiments, relate them to the syllabus, and practise them to see if they work in a classroom," she says.

These points are supported by the experience of 16-year-old Oriel student Emily Rickman, who is planning to take both physics and chemistry at A-level. "Experiments have probably become less frequent during my GCSE years," she says. "But throughout school, doing experiments has been a big part of making science interesting for me, because they helped show us the practical side of the theory and equations."

Last week's survey findings confirm long-held fears of the professional scientific institutions. An unacceptably large proportion of school children are not getting the practical experience they need in science lessons, according to the Royal Society of Chemistry's chief executive Richard Pike.

In addition to curriculum pressure, a contributory cause for him is a shortage in many schools of science teachers who are graduates of chemistry or physics, and therefore have the expertise and confidence to let children loose with experiments. This is a phenomenon also identified at the Institute of Physics.

"Too many physics lessons are still being taught by non-specialist teachers who don't have the confidence to work with physics apparatus," says Charles Tracy, head of pre-19 education at the institute.

The Conservatives' education spokesman Michael Gove sympathises with the predicament of teachers grappling with a demanding curriculum. "I am a strong believer in practical learning," he said in a speech critical of Government changes to the science curriculum, which, he argued, take pupils away from the essential disciplines of physics, chemistry and biology.

"I would like to see a bigger place for practical experimental work in science teaching."

The Government, however, rejects that charge.

"The new primary and secondary curriculums give teachers far more freedom to teach their subjects in ways they think will be the most engaging, interesting and relevant to their pupils," said a statement from the DCSF. "And that includes practical experiments."

Ministers have implicitly conceded, however, that some, if not all, schools need to raise their game, because they are funding a campaign called Getting Practical run by the ASE. Two hundred of the most experienced science teachers will be visiting schools to run training and discussion sessions for their colleagues.

The aim is to have more teachers able to deliver experiments like the Oriel jelly baby one that will stick in the memories of pupils, and cement scientific concepts in young minds.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments