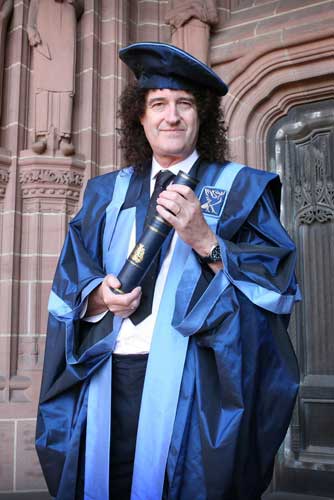

We are the champions: the new chancellors

Queen's guitarist Brian May epitomises the kind of chancellor being appointed to universities today – hip, anti-establishment and in touch with students. Lucy Hodges looks at how an ancient role has changed

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What does a university chancellor do – hand out degrees, dress up in fancy garb, make speeches, chair meetings or schmooze? The answer is that he or she does all those things, and more – hopefully with a smidgen of charm, wit and style.

He or she is no longer a stuffy figure, but is as likely to have been a rock guitarist or an actress or, God forbid, a journalist. So, lead guitarist Brian May, of the rock band Queen, is the new chancellor of Liverpool John Moores University; Dame Diana Rigg is chancellor of the University of Stirling; the writer Bill Bryson is chancellor of Durham; and Jon Snow, the Channel 4 newscaster, is chancellor of Oxford Brookes.

All go about their duties with commendable earnestness, according to a new booklet, Beyond Ceremony: On being a chancellor, published today by Universities UK, which aims to give advice to new chancellors on how to do the job.

The one thing that a chancellor does not do is run a university, Rick Trainor, president of Universities UK and principal of King's College London, reminds us. So, although it sounds as though the chancellor should be the Number One, and the vice-chancellor the Number Two, that is not the case. The chancellor has no executive powers and is unpaid. Most students will only come across him when he gives them their degrees on graduation day.

Chris Patten, former governor of Hong Kong, is probably the most high-profile chancellor in Britain as he likes to stir things up with provocative speeches about state schools not producing enough good applicants for universities such as Oxford.

He has more experience than most of the job because he was chancellor of every university in Hong Kong and is now chancellor of both the universities of Oxford and Newcastle.

It is important to preside at degree-awarding ceremonies with as much élan as possible, he says. "For students and their families, these ceremonies are an important rite of passage. They should feel afterwards that the journey was worthwhile."

The broadcaster Floella Benjamin, chancellor of the University of Exeter, agrees. "I believe this is the primary role of a chancellor," she says, "to make graduations memorable, uplifting and celebratory occasions."

The role is steeped in history. No one knows who was the first chancellor of a British university because the title is so ancient, but it may have been Robert Grosseteste at Oxford in the 13th century. Monarchs would appoint their favourites to chancellorships. Thus Thomas Cromwell, who advised King Henry VIII on England's break with Rome, was chancellor of the University of Cambridge from 1535 to 1539.

Former politicians are still to be found in the post, notably the ex-Conservative ministers Baroness Bottomley (Hull) and Lord Wakeham (Brunel), and the Lib Dem Sir Menzies Campbell (St Andrews). But royalty also graces chancellorships – Prince Charles (the University of Wales), the Duke of Edinburgh (Cambridge and Edinburgh) and Princess Anne (London).

The job contains some surprises, according to Virginia Bottomley. She recently learnt, for example, that she had to arbitrate in a dispute between the foundation that runs the beautiful Burton Constable Hall and the Constable family who lived there for 400 years.

She takes the job of championing the university seriously by speaking in the House of Lords when necessary – in one higher education debate Hull received more mentions than any other university. She also hosts dinners for senior dignitaries from countries sending overseas students to Hull and plays a quiet role advising the top management. Chancellors can see the big picture, she says. "Unofficially the chancellor can be an honest broker and smoother of 'ruffled feathers' should emotions run high over an issue," she says.

A number of chancellors are former vice chancellors, so they have run universities and know the issues back to front. One of them, Sir Kenneth Calman, former boss at Durham, now chancellor of Glasgow, enjoins his fellows to enjoy the job. "Always have a speech ready. You never know when you will have to speak. Keep them short and amusing."

He also advises chancellors to support their vice-chancellors in every way possible and to get to know the university by visiting departments and research groups. Sir Menzies Campbell sums it up: "Chancellors should be seen often, and heard rarely," he says.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments