Is it time for radical solutions when it comes to getting poorer students into top universities?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

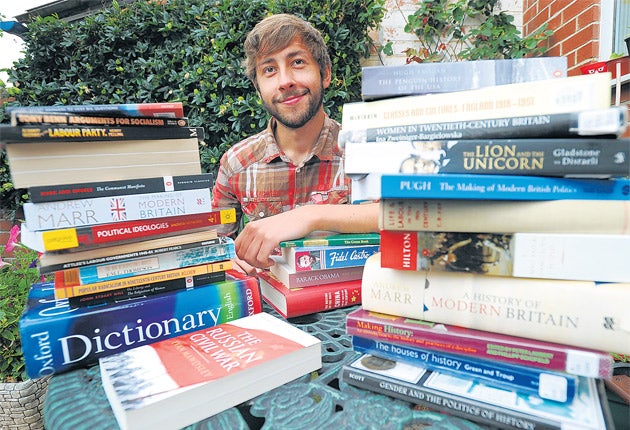

Your support makes all the difference.Andrew Seaton, 22, is one of a rare breed – an ambitious student from a deprived background, with four grade As at A-level, who has just completed his first year at Oxford University.

He believes that Oxford and Cambridge should take many more students like him, but has no easy answers about how this can be achieved and is sceptical about the idea of Vince Cable, the Business Secretary, that Oxbridge colleges be forced to reserve places for a certain number of pupils from a wide range of schools.

The merit of Cable's wheeze is that it would widen participation. "You would have a higher state-school intake," says Seaton. "Obviously that's a positive thing, but I worry it would be too rigid, keeping out good people and letting in some who might not be suited to the work."

Seaton had never thought about applying to Oxford or Cambridge because no one in his family had been to university. "The idea was new and strange to me," he says. "I was planning to go to Bristol, but I got straight As in my AS-levels and decided to apply to Merton College, Oxford – not realising that it was one of the top colleges." His first attempt was unsuccessful but he tried again after achieving four As at A-level, this time applying to Mansfield College, which has the highest percentage of state-school students of all Oxford colleges. His interviews went better this time, he says, and eventually, after being recalled for a third interview, he got in to read history.

"In the first year I did find it hard to adjust to the level of work but I got used to it," he says. "I am lucky to be learning so much and to have close contact with such incredible academics. I consider myself really lucky to live in an age and a country where you can do this."

Seaton is endearingly appreciative of his parents and his teachers. He was home-schooled for years (his parents were cleaners, chasing jobs in different parts of the country), but that enabled him to read voraciously and to teach himself. When he finally returned to an educational establishment – Exeter further education college – he was on free school meals, and taking first GCSEs and then A-levels.

Both ancient universities say that they are bending over backwards to find the best people to fill their places and that they trawl from a much wider pool than previously. Oxford flags up applicants from non-traditional backgrounds during the application process to ensure they get every chance for an interview; it has contacts with most schools around the country that have students who can make a competitive application; and it runs summer schools, residential programmes and e-mentoring schemes.

Nevertheless both Oxford and Cambridge still take extraordinarily high numbers of students from independent schools. At Cambridge, for example, 58 per cent of undergraduates are from state schools. On the face of it, this looks modest when you think that 93 per cent of the school population is state-educated, but the general trend is upwards, according to Cambridge's admissions director, Geoff Parks.

The fundamental problem is that relatively few students from the lowest socio-economic groups achieve three As at A-level, as Seaton did. So, Oxford and Cambridge, as well as other leading universities such as University College London, the London School of Economics, Bristol, Durham and Nottingham, are fishing in a small pond.

Only 3 per cent of students from the lowest socio-economic group achieve three A-levels, compared with 25 per cent in the highest. Professor Claire Callender, of Birkbeck College London, is blunt about the problem. "I generally believe that Oxbridge try to do as much as they bloody well can," she says. During the Blair years universities were named and shamed for the percentage of independent school pupils they recruited. A multi-million-pound Aim Higher campaign was launched to persuade more state school pupils to apply to university, and Gordon Brown criticised Oxford for not admitting Laura Spence, a medical student who ended up going to Harvard University in the US. The issue became politically very hot – and remains so to this day.

Medical schools such as King's College London and St George's introduced innovative programmes. In 2001 King's began a six-year medical degree which takes more than 300 students from comprehensive schools in London, Kent and Medway, including a high percentage of ethnic minorities. Applicants are taken on much lower grades than the norm, and have done amazingly well, winning prizes and getting good degrees.

Experts in the universities maintain that the problem with access lies mainly in the schools. They say that state secondary schools need to do more for their pupils – give them better advice about the subjects they choose to study at GCSE and A-level to ensure they have a chance of a place at a good university; encourage them to be ambitious and to apply to high-status institutions; and give them help with preparing for Oxbridge interviews.

"The main barrier to poorer students going to university is prior achievement, so I maintain that one of the best ways to improve access is to face problems in schools," says Professor Anna Vignoles, of the Institute of Education in London. "There are problems with higher education, too. It's not always clear, for example, how to get into a university or what the benefits are after you graduate. Universities need to be more transparent about where their graduates go and what they're earning, as well as highlighting the benefits of getting a degree. But to make serious inroads into the access question you have to solve the problem of pupils' qualifications."

Her point is that students are not turned away because they are poor or because they come from families with no knowledge of higher education, but because they have done the wrong subjects or haven't achieved enough at school. Some recently published figures make gloomy reading. Bright children from the poorest homes are seven times less likely to go to top universities than their better-off peers. This is partly because their schools don't offer modern languages or single sciences as the independent schools do. And that gap has grown since 15 years ago, when the richest were six times more likely to get a place in the top third of universities, according to the Office for Fair Access (Offa) in a report this year.

Offa believes that the gap has increased because the number of students from the most selective schools achieving high grades has increased. At the same time competition between universities has grown, and more and more people have become aware of the hierarchy of universities. So, although widening participation has worked, it has happened above all in the bottom two-thirds of institutions.

To get round this problem of the sector becoming more unequal over time, experts believe that universities need to work closely with disadvantaged schools to identify bright children at the age of 13, before they make their GCSE choices. Then the universities need to lay on special help, enrichment courses and mentoring for these students to make sure they understand why university is a good idea. "If you can get children pre-GCSE and give them support over two or three years so that they get up to the level required, then you can start to change things," says Lee Elliot Major, research director of the Sutton Trust. "Like Vince Cable, we're all in favour of thinking very radically about this, but there are no simple answers."

An even more extreme idea than Cable's has come from Peter Wilby, the first education editor of The Independent. Wilby proposed that Oxford and Cambridge offer places to the top one or two pupils from every school, regardless of their grades. The next-best universities would offer places to the pupils who came third and fourth, and so on.

The problem with both ideas is that they conflict directly with universities' admissions policies. Cambridge says that it won't introduce targets or quotas for people from certain backgrounds. "We feel very strongly that applicants should be admitted on academic merit and on their potential to succeed on their chosen course," says Cambridge's Geoff Parks.

One of the difficulties of introducing Cable's idea, according to Andrew Seaton, is that much of the teaching and learning is based on how a student performs in tutorials. You have to be able to explain yourself and articulate an argument.

"You have to be able to talk about your ideas and defend them," says Seaton. "That's the kind of education you get at private school. You are taught how to speak."

Educational Elite

* Intelligent children from the richest 20 per cent of homes in England are seven times more likely to attend a leading university than intelligent children from the poorest 40 per cent. This gap has widened since the mid-Nineties, when they were just six times more likely.

* At Oxbridge 48 per cent of students reading science, maths, languages and technology came from private schools in 2006-07, compared with just under 47 per cent in 2003-04.

* According to the 2009 Milburn report on social mobility, 45 per cent of top civil servants, 53 per cent of top journalists, 32 per cent of MPs, 70 per cent of finance directors and 75 per cent of judges came from the 7 per cent of the population that went to private schools.

* The link between background and attainment is evident at 22 months, and schooling widens it. Fewer working-class children take A-levels, and those who do get lower scores. Pupils at private school account for 15 per cent of A-level entries but account for about 30 per cent of the A grades.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments