A new initiative aims to resolve the critical shortfall in the number of young engineers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The new higher-education academy launched this month to solve the malaise affecting the engineering sector has no money and no buildings. When placed alongside other academies we're used to reading about, it ain't much cop.

But this isn't your typical academy. For a start, it's virtual. The E3 Academy – the three Es being "electrical energy engineering" – is more of a coalition, a network of companies and two universities that have come together to sponsor the next generation of electrical and electronic engineers through university.

The sponsorship is open to students wishing to study electrical and electronic engineering courses at the University of Nottingham or the University of Newcastle. Successful applicants will receive an annual bursary of £2,500 from their sponsor company, plus eight weeks' paid summer-holiday training (worth another £2,500) and places on summer schools, reimbursement of tuition fees after graduation and possible employment with one of the partner companies, such as Siemens.

The initiative, which has been operating unofficially since last September, is aimed at resolving the problem that has dogged engineering since the turn of the 20th century: dwindling uptake on degree programmes. Between 2001 and 2006, against the backdrop of a swelling overall student body, the so-called "stem" subjects – maths, science, technology and engineering – have seen a 15 per cent increase in uptake, while engineering itself has gone up just 5 per cent.

Electrical and electronic engineering has seen a staggering 45 per cent tail-off. "Numbers are painfully low," says Professor Paul Acarnley, manager of the E3 Academy. "Everybody who spoke at the launch said that it's a permanent recruitment campaign."

One of those who spoke was Richard Lambert, the director-general of the CBI, who warned that the fall-off is already having an effect on companies, and that the crisis threatens to engulf UK industry. "About three- quarters of our engineering companies expect a shortfall in recruitment this year," says Lambert. "More companies are having to recruit internationally to fill the gaps, but other countries have the same problem. Sometimes the quality is not what we are looking for. We are not only risking our established businesses in the UK, but it also makes us less attractive to international companies looking to invest because they will want to be sure that the skills base is available."

So what's the problem? Chisti Sadat, 29, from Bangladesh, is studying for a BEng in electrical and electronic engineering at the University of Nottingham, and is being sponsored by Cummins Generator Technologies, as part of the E3 Academy scheme.

"Of all the students in Bangladesh, the cream go for engineering because engineers are held in very high esteem, alongside doctors," says Sadat. "Here, doctors are much more respected."

By contrast, British engineers are seen as having neither the reputation nor the financial clout. "There is that thing about status," says Acarnley. "People think that if you become a company's lawyer, you will earn more than the company engineer, which is not necessarily the case."

There are also problems in our schools. Physics syllabuses now play down subjects such as electricity and magnetism, giving pupils less grounding in the basic principles of electrical engineering. There are also concerns that sixth-formers are shying away from "harder" subjects, in particular, mathematics. This drift towards softer A-levels is being seen in higher education, too, with universities closing, reducing entry and replacing industry-oriented courses with trendy alternatives.

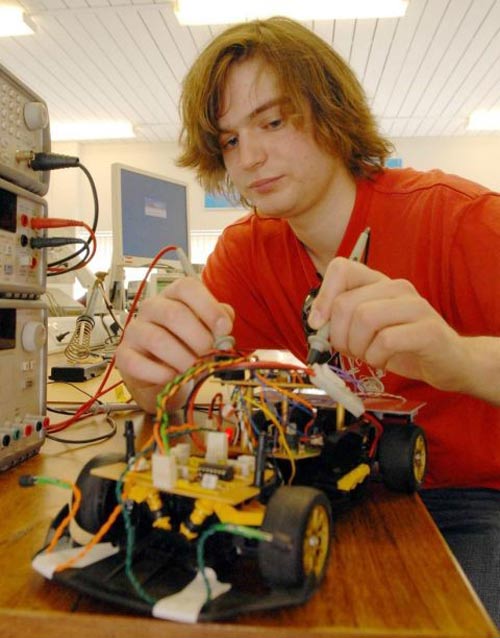

The dotcom crash of 2001 put the fear of God into many prospective electrical engineers and computer scientists. Some 60 per cent of electrical-engineering students do not pursue a career in that field. This is perhaps the main area in which the E3 Academy could help, by drafting students into companies at an early stage. "With the E3 Academy scheme, you get a lot of experience early on – which is the main thing," says Mark Towers, 21, who is studying at the University of Newcastle and was one of the first students to be accepted into the E3 Academy. "Otherwise, it would be difficult to get a placement early on in your course."

The need for the E3 Academy is clear. The apparent shortfall in the number of engineering students has been exacerbated by a steady increase in demand for expertise in this area. "With these companies, if anyone comes to them with the right skills, they will create jobs for them," says Acarnley.

The E3 areas of engineering are all around us and are responsible for more than half of the world's energy. This summer, students in the E3 Academy will even visit the Royal Opera House, where more than 1,000 electric drives are pulling the strings of the lighting, stage and scenery.

The academy, like the Institute of Engineering and Technology's Power Academy, which covers power transmission, has restricted itself to a niche market, because it wants to create a close network for its students.

"We are not trying to cover the whole of engineering, because you'd just end up with a lot of people who didn't know each other, and you wouldn't have that sense of community," says Acarnley.

The engineering exodus will not be cured overnight, and the feeling is that the root causes start before the age of 18. But the E3 Academy is not intended as a long-term solution. "We see the bursaries, and the fact that we're a network, as a step that will meet companies' immediate demands," says Professor Greg Asher, head of the school of electric and electronic engineering at the University of Nottingham, and the university's representative in the E3 Academy. "In the long term, we've got to work with the Institute of Engineering and Technology, the Royal Academy of Engineers, and local schools. We have to increase the level of exposure."

Design for life

Mark Towers, 21, from Gateshead, is in the first year of an MEng in electrical and electronic engineering. He is being sponsored by Control Techniques Ltd as part of the E3 Academy scheme.

"You notice that there aren't many people going into engineering. Part of the problem is that it's seen as being quite a difficult subject because you need the maths to do it. It's also seen as a hard degree: you've got a lot more contact hours and you have an awful lot to learn on top of that.

"We have a problem nationally with the perception of engineers, compared with somewhere like Germany, where engineers are held in high esteem. Over here, people aren't quite sure what engineers do or who they are.There's a public misunderstanding.

We live in a time when just about everyone uses technology on some level, which is generally considered to be a good thing. So I don't see why people aren't interested in getting on with the design of this technology. It's the same with climate change: we're always talking about it but no one's interested in designing the solutions. But this is the only way things are going to move forward." AS

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments