From league tables to using the cane: Looking back on 36 years as an education reporter

As he retires, Richard Garner bows out with a retrospective on what's changed in schools

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

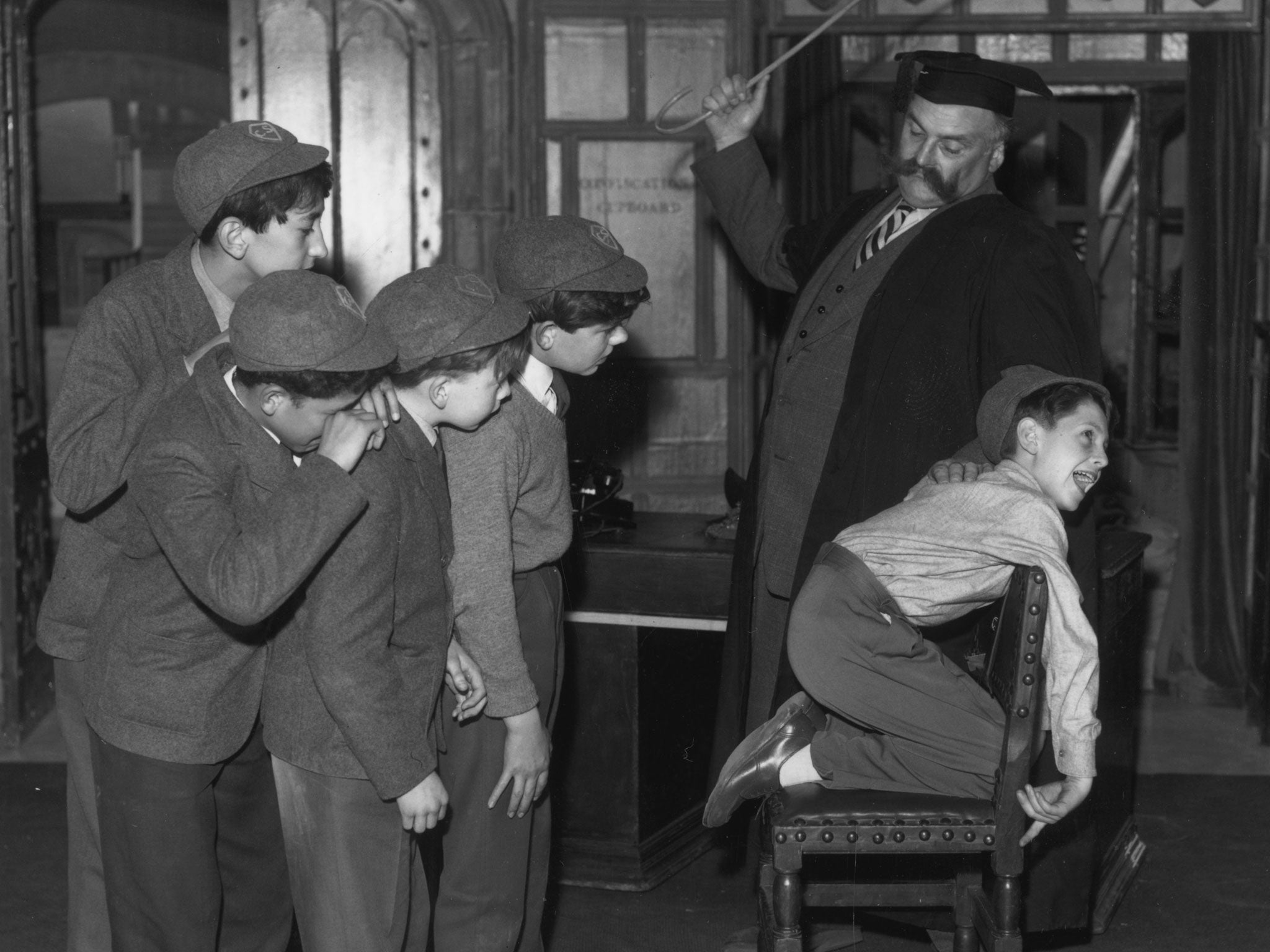

Your support makes all the difference.It was all so different back then. Thirty-six years ago, pupils could still be caned at school, reading standards had shown no improvement since the Second World War and, yes, there was controversy over teachers’ pay.

It was the year, in 1980, that I started reporting on the national education scene – at the beginning of the Thatcher government, though it would be another eight years before it turned its full attention to reforming the education system.

That all comes to an end today as I complete my stint as education editor of The Independent.

So what has changed? And has it been for the better? Well, for a start, in 1980 there was nowhere near so much government control of the education system as there is now. Jim Callaghan, when he was Prime Minister, had floated the idea that “something should be done” about education, in his speech at Ruskin College in 1978, but the consultation over that had borne forth little fruit by the time Labour left office in 1979.

It was Kenneth Baker, with his GERBIL (Great Education Reform Bill), who sowed the seeds of what was to follow in the late 1980s. He ushered in local management of schools (with hindsight, the forerunner of academies), the national curriculum, and testing of seven-, 11- and 14-year-olds. The latter years of the Thatcher government also paved the way for the creation of the education standards watchdog Ofsted (previously, inspectors’ reports were not made available to the general public) and exam league tables. Schools were also given the opportunity to opt out of local authority control.

To my mind, one of the most successful reforms of the last 36 years was the abolition of corporal punishment in 1986. We became a civilised society that no longer beat its children This was largely as a result of the move being passed in the Commons by one vote when Mrs Thatcher was delayed from getting there by traffic. She would have voted against abolition.

The second most successful reform was the improvement in literacy and numeracy standards in the first years of the Blair government, when the then education secretary, David Blunkett, introduced literacy and numeracy hours in primary schools.

I realised that exam league tables were here to stay when – in a previous incarnation to my job on The Independent – I was education correspondent of the Daily Mirror when we took the principled stand not to publish them, as we believed they were not a fair reflection of a school’s achievement. That day, though, I had several senior executives from the Mirror crowding round my desk to see how their children’s schools had performed.

As far as Ofsted is concerned, I welcome the independent scrutiny of schools and – my goodness – hasn’t the current chief schools inspector Sir Michael Wilshaw been independent? He was appointed by Michael Gove, who saw in him a man after his own heart, but the two fell out when Sir Michael began criticising academies and free schools for their faults in the same way as he had done with local authority schools. In my view, he was quite right – just as he was to point out the shortcomings of multi-academy trusts in a letter to the current Education Secretary, Nicky Morgan, just before the recent announcement that schools were going to be forced to become academies.

Which brings us on to the current controversy: is it right to compel all schools to become academies? No. Not while evidence appears to show that local authorities are making a better fist of improving schools than academies are. As Gerard Kelly, the former editor of the Times Educational Supplement (another organ I have worked for) put it to schools minister Nick Gibb at the Association of Teachers and Lecturers conference this week: it is difficult to understand why a good local authority school that’s doing very well should have to become an academy. (Interestingly, the Government appears to have changed tack in the defence of its plan – Mr Gibb stressed the fact that the decision had been made to avoid a situation where a local authority had too few schools under its command to look after them effectively and that a two-tier system for running schools would not work.)

I also think it was wrong to insist that every new school should be an academy or free school. At a time of rising pupil numbers, local authorities need the power to react to the local situation. While I accept that most free schools have been set up in the areas of greatest need, there have been several occasions when local authorities have been forced to compel existing schools to expand against their will because they do not have the power to open a new school to cope with the problem and no free school has been proposed for the area.

So what of the future? I do foresee that the period of calm brought in when Ms Morgan succeeded Michael Gove is over – there is bound to be ongoing controversy over the academisation proposals, especially now that Conservative backbenchers have weighed in against them. I can foresee the Government having a hard time getting them through Parliament.

There are some bright spots on the horizon, though. Witness the growth of University Technical Colleges (UTCs), which give 14- to 18-year-olds the opportunity to develop high-level vocational skills. It surely has to be a better way of preparing our young people for the modern world, to give those who would prefer to be engineers or technicians the chance to develop skills in these areas rather than force them to continue with a diet of academic education.

It would make sense to abolish selection at 11 (we still have 164 grammar schools in this country) and concentrate on choice at 14 instead. Incidentally, as the founding father of the UTCs – Lord (Kenneth) Baker – told me, that was the original intention of the architects of the 1944 Education Act, which brought in universal education. They were talked out of it because it was felt it would be too much upheaval for the system. Would that they had witnessed what has happened in the last five years!

On reflection, then, some hope for the future – and some fears, too. I would just leave you with one wish: treat teachers as professionals, not guinea pigs for constant change. After all, you wouldn’t dictate to a brain surgeon how he or she should do their job, would you?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments