The Big Question: Why has the drive for healthy school meals faltered, and can it be revived?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

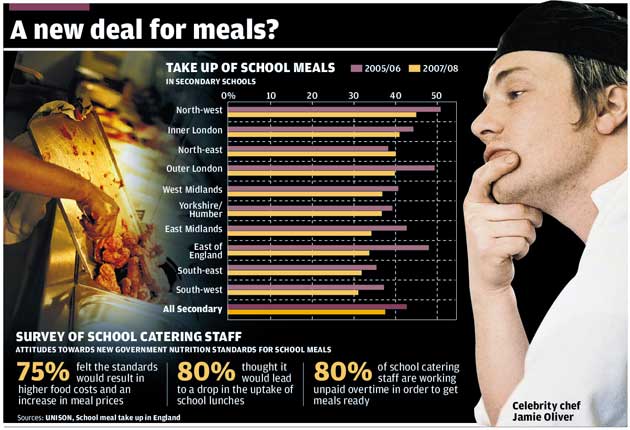

The Local Authorities Catering Association has warned there will be a dramatic decline in the take-up of school meals in secondary schools once new nutritional guidelines are introduced this September. It warns that many youngsters will nip down to the local "chippie" or burger bar at lunchtime because of the lack of choice in school canteens which will not be serving food they want.

Why do they think that?

The LACA says that the new guidelines are too complex – so complex, in fact, that school meals providers will have to use a computer to check whether they have got the ingredients right and are complying with all the regulations. For instance, they have to abide by 14 nutrient-based standards – including ensuring the average secondary school lunch contains no less that 7.5g protein and 5.2mg iron. They say the only way schools will achieve this is if they offer just one meal to pupils – drawing up a menu offering alternative dishes which comply with requirements would be too time-consuming.

Do they have some evidence to back these assertions up?

The LACA conducted a survey of staff which showed that nearly half (48.6 per cent) of secondary schools will fail to meet the deadline for implementing the new guidelines. In addition, 80 per cent believed they would lead to a decrease in take-up in the schools.

Does this stem from the Jamie Oliver's campaign?

Partially, yes. It is certainly true that the Government's drive to improve the nutritional standards of school dinners was announced by Tony Blair on the day Jamie Oliver turned up outside 10 Downing Street with a 270,000-strong petition calling for more money to be provided for the service. The then Education Secretary Ruth Kelly modestly claimed that she deserved some of the credit, too. To be fair to her, she has been battling away in Cabinet calling for healthier school dinners before the celebrity TV chef's Channel Four series took to the airwaves. However, she was not able to muster support for her aims before the "Naked Chef" appeared.

What happened following that campaign?

It was a victory for the cynics who said that it would never work. Take-up of school dinners actually dropped by five per cent to just 37 per cent in the first year following the introduction of the initiative. At that stage, the initiative consisted of £280m to improve school kitchens and help schools provide organic food and healthy eating options rather than just provide burgers, chips and pizzas. There were also pictures of angry mothers in Rotherham passing burgers through the school's railings to their children because they were up in arms about healthy school dinners. Last year, a study by the Nutrition Policy Unit at London Metropolitan University warned that too many children were shunning healthier canteens in favour of local shops – a serious blow to Oliver's campaign.

What else changed as a result of the campaign?

School vending machines and tuck shops came under scrutiny as never before. As a result, items like chocolate and fizzy drinks were banned from them two years ago.

What is the picture now?

The decline stabilised last year (take-up went down by 0.1 per cent in secondary schools while there was actually an increase in primary schools). Prue Leith, appointed as school meals "tsar" by the Government – she chairs the School Food Trust set up by the Prime Minister to deliver reforms – indicated that she had just three years to convince the nation's seven million school children that healthy dinners were better for them. Otherwise, she said, she feared that people would "lose faith" in the campaign. The food and cookery writer said: "I am told that the fall-out is very common and a not unexpected blip when you start to do something that's new."

How important was the healthy schools plan?

The Government thinks it is very important indeed. It is battling with a growing obesity crisis in schools (if you'll pardon the pun) which could lead to more than half the nation's children classified as obese by 2050. Teachers also report that pupils – particularly those from the most disadvantaged areas – often come to school without any breakfast and no longer sit down for an evening meal with their parents.

As a result, the school dinner is the only chance they have to eat healthy nutritional food during the course of the day. (Schools were also encouraged to set up breakfast clubs providing youngsters with a healthy option before they started school. Those that have done so report that pupils' concentration has improved as a result. A similar picture emerges in the afternoon with those pupils who have had school dinners, say teachers.

So what does a typical school dinner look like now?

In a primary school, there will be a balance of popular foods (such as pizza and minced beef) with more adventurous items (salmon fishcakes and vegetable risotto). The menu should always include an item for vegetarians or pupils not wanting beef or pork. Chips will not normally be on the menu. There will also be two portions of vegetable or fruit daily. In secondary schools, the food must be filling enough to keep the temptation to purchase crisps or fizzy drinks at bay. Fresh fruit and vegetables again should be available.

So why change this?

Many children interviewed yesterday said the same thing, but the School Food Trust insisted the tighter nutritional standards – although "challenging" – were necessary. Among other things, they set out the calorie, fat and vitamin contents of school meals. "It is important that they are in place to ensure we promote the health, well-being and achievements of students and we will not fall at the final hurdle," a spokeswoman said. Children's Minister Delyth Morgan added: "We need schools to provide more fruit and vegetables and less food with high amounts of fat, salt and sugar so that we can reduce obesity and protect the health of our children – we make no apologies for this." She added that schools which had been piloting the new programme had not noticed any fall in the take-up of dinners. However, some point out that the introduction of the new nutritional standards into primary schools last September has gone relatively smoothly. The LACA insisted it would be more difficult in secondary schools – where the numbers of pupils requiring dinners are much larger. It said it would be coming up with alternative suggestions for meeting improved nutritional standards before the final deadline for secondary school introduction in September – but maintained its insistence that the new standards were too prescriptive.

So what will be the likely outcome of all this?

It could be, argue some local authority providers, that the new guidelines have the same effect as the immediate post Jamie Oliver TV programme school dinner campaign: an initial falling off of the numbers followed by a stabilisation of the process. Meanwhile, ministers are only too well aware that their campaign can only be considered a success once both secondary and primary school take-up has actually increased.

Has Jamie Oliver's campaign actually harmed efforts to create healthy kids?

Yes...

* In the year following the campaign, take-up of healthy school meals fell by 5 per cent in secondary schools

* Researchers said more children were swapping school premises at lunchtime for fast-food chains

* Even tougher nutritional guidelines being introduced may lead to an even bigger fall in healthy eating at school

No...

* Take-up stabilised in the second year – and an increase was recorded in primary schools

* Teachers reported pupils' concentration increased in the afternoon if they had eaten a school dinner

* Some experts believe any further decline in take-up this September will be temporary and short term

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments