Strength in numbers: Teaching maths that relates to the real-world

As the Department for Education announces a new ‘real-world maths’ qualification to stop students dropping the subject after GCSE, Richard Garner visits a college that is already teaching maths that relates to real life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The new ruling, designed to ensure the country becomes more maths literate, came into force this September, so Hollie and her classmates at Abingdon and Witney Further Education College in Oxfordshire are among the first in the country to face the new regime.

Hollie, who is studying performing arts at the college, says: “I would have got a C grade if I’d stuck with the foundation paper, but I was doing well, so my teachers suggested that I changed to the higher tier a few months before the exam. I was annoyed and disappointed when I heard that I’d have to carry on taking maths classes because I would have liked to concentrate on my main area of study which is performing arts.”

Happily, though, the maths lessons – she is retaking her GCSE – have not proved as daunting as she feared. Her teacher, Greg Bason, tries to relate maths to the everyday experiences of his pupils, so that the problems they have to solve coincide with the areas of study that they are interested in.

Hollie hopes to go on to take an apprenticeship in hospitality once she has finished her college course – an area in which she acknowledges that an ability in maths could be helpful.

The new proviso has meant a sea change in the way that colleges operate. Firstly, they need to find a new army of maths teachers to take the courses. More than 2,200 numeracy teachers and trainers have signed on to a maths-enhancement programme run by the Education and Training Foundation (ETF) during the past year to help fill the void. In some cases, it has meant existing lecturers being trained specifically to teach GCSE maths.

“All types of further-education providers are involved: including large employers, independent training providers, colleges and adult and community learning institutions,” says the ETF. “The programme will particularly benefit teaching staff who wish to develop their knowledge and skills to teach maths GCSE.”

Take Jason Crouch, for instance. The 27-year-old admits to having had a difficult time at school: “They didn’t do a great job of helping me,” he says. He did get a C grade in maths but then went on to work as a welder. He was, though, interested in boosting his qualifications and attended an open day of the college where, he says, he met a “brilliant” maths teacher and was persuaded to take an AS-level followed by an A-level in the subject and then study for an Open University degree. “I got a first,” he says triumphantly.

Even then he did not at first pursue maths teaching as a career. “I wasn’t aware that there was a job doing that here,” he said. “I looked at teaching in a secondary school but decided it was going to be too intensive.”

Eventually, though, a job cropped up at his old school and he took it. “I think it is really fantastic because we are also helping students overcome their phobia of maths – it’s really rewarding when it comes out right for them.”

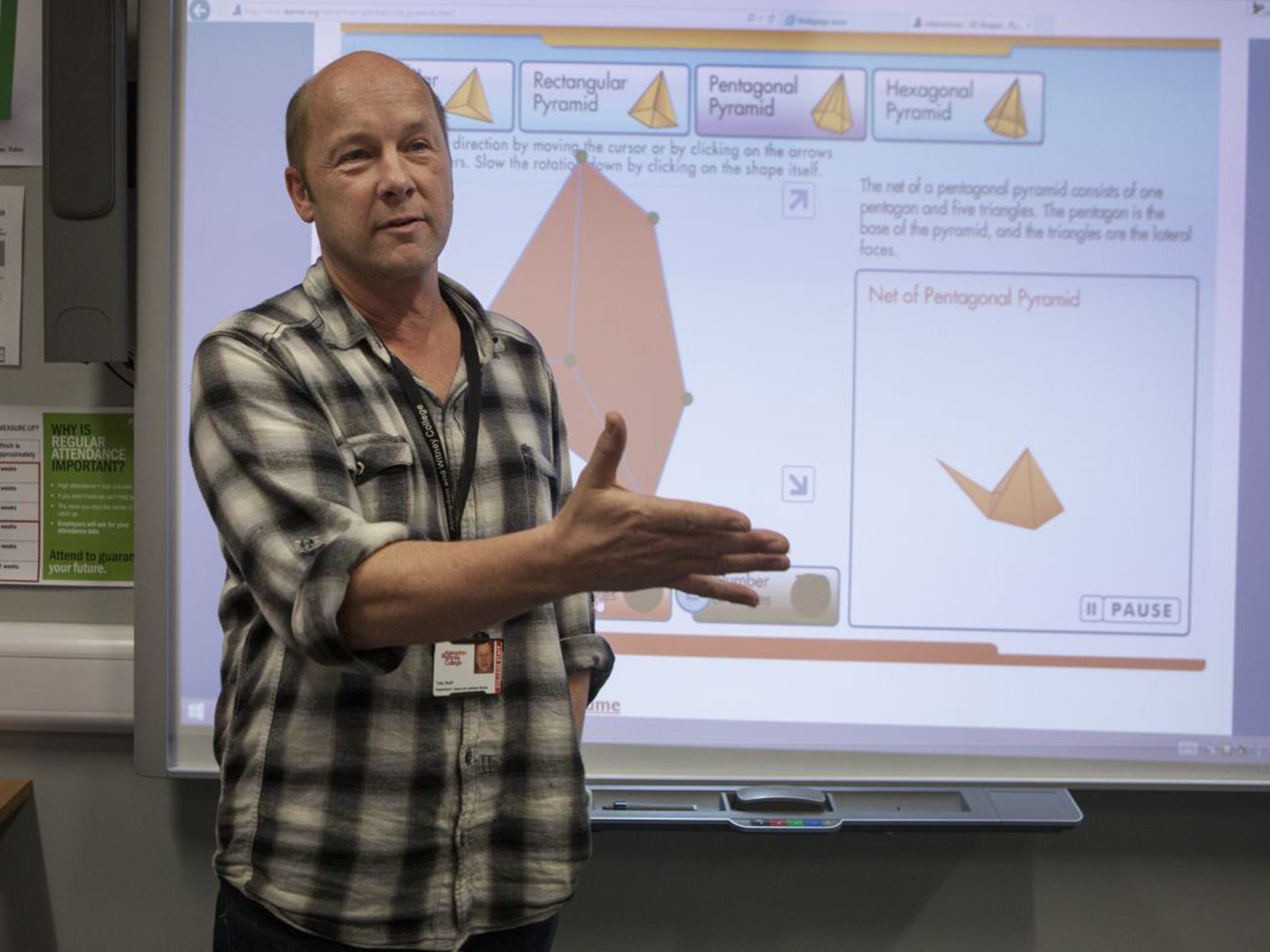

Toby Swift’s story is even more remarkable. “I left school with a U in maths and did lots of practical work like tree surgery,” he says. “I went back to night school to take my maths GCSE. I got my teaching job and was teaching lots of basic-skills maths and English.” He went on the maths-enhancement programme and is now qualified to teach GCSE classes. “It was clear to me that I did have some maths knowledge and so I thought I’d have a crack at it,” he says. “I think it’s going OK.”

Because of their history, both Jason and Toby can relate to students who are struggling to master the subject. In Toby’s case, there were any number of problems that needed solving in his conservation and tree-felling classes through maths – such as working out angles to make tree felling easier. “We basically tell them [the students] that they can do it,” says Maureen Boyle, the college’s assistant principal.

“It is a small number of students who have had such negative experiences that they’re not in the right place to study it,” adds Anne Haig-Smith, head of the college’s maths and English faculty. “We’re relentless, though. We find ways and means of getting to them any way that we can – whether it’s working out the portions for their hair colours in hairdressing or whatever.” Sometimes, she adds, they did not realise they were doing maths until after they had solved a problem. “They just do it automatically,” she says.

Further-education colleges have often been labelled the “Cinderellas” of the education system. However, the colleges cater for 846,000 16- to 18-year-olds, almost twice the number that go to maintained school and academy sixth-forms. And the new maths policy has given them a more mainstream role. Ministers have acknowledged their programme cannot be delivered without enlisting the aid of the further education sector.

Nationally, around 40 per cent of 16-year-olds fail to get a grade C at maths and/or English at GCSE – and 90 per cent of those still have failed to do so by the time they have reached the age of 19. Another problem is that the younger maths teachers are far less likely to have a degree in the subject than their older counterparts – one in three over 55s teaching maths in the sector has a degree in maths or a related subject compared with only 10 per cent among those aged under 34.

Bursaries to teach in the sector have been increased to £25,000 a year for those with a first-class degree in maths. In addition, the college can access £30,000 in help for training a new graduate teacher. Of those teachers who have been on the maths enhancement programme, around 85 to 86 per cent complete it successfully. “It’s a pretty good completion rate,” says Helen Pettifor, director of professional standards and workforce development at the ETF. “It has improved the quality of teaching and the number of teachers in the profession.”

Which all means that students such as Hollie and her classmate, 18-year-old Michael Coombes, who got a D in maths at school, stand a better chance of succeeding in the subject at college. Michael is also studying performing arts. He may not have wanted to study maths again – but at least he and his classmates have been engaged by the subject this time round.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments