Pay exam markers better to improve standards, says independent schools' chief

'We find it unacceptable that there are so many re-marks and regrading of exams – both at GCSE and at A-level'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

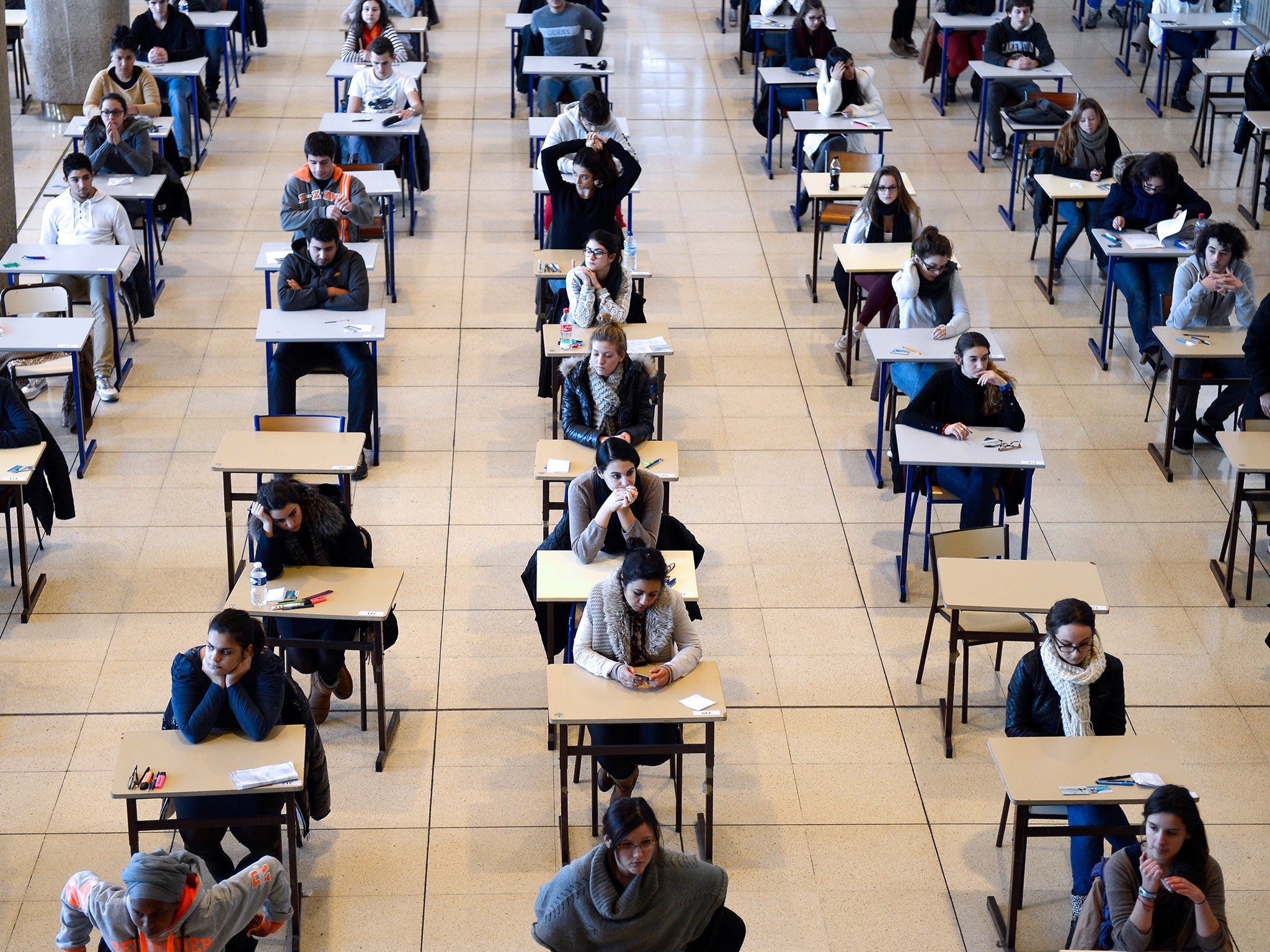

Your support makes all the difference.Concern about the marking standards of GCSE and A-level papers will be voiced by leaders of Britain’s top independent schools this week. Christopher King, the chairman of the Headmasters’ and Headmistresses’ Conference (HMC) and headteacher of Leicester Grammar School, will argue that markers should be paid more so that exam boards can demand a higher standard from them. His argument is that higher pay will attract more markers of a higher quality.

In an exclusive interview with The Independent on Sunday in advance of the conference, which opens on 6 October, he said: “We are very concerned about the quality of marking of public exams. We find it unacceptable that there are so many re-marks and regrading of exams – both at GCSE and at A-level. The review process and the appeals process is also simply not transparent. We need a review of the process of marking and the quality of markers.

“This is for the benefit of all pupils – not just those in the independent sector. It’s expensive to appeal against grades and many schools don’t have the resources that independent schools have to do this.”

As a result, teenagers at state schools are likely to be robbed of the chance to test whether their grades should have been higher, and thus could miss out on university or sixth-form places. Last year there were a record 122,500 appeals against A-level grades, and 23,200 were changed. Both figures are twice as high as four years previously.

Mr King also voiced concern over the trend by exam boards to get examiners to mark individual questions rather than a student’s whole paper. “The exam boards will say it helps to develop an in-depth knowledge of the particular question assigned to them,” he said, “but then there is not the same accountability for marking a paper overall.

“If you have 10 different questions, you can have 10 different markers and they could all err on the side of generosity, whereas somebody who has seen the whole paper will say ‘Well, I’ll err on the side of generosity once but I’m not going to do it twice or three times.’

“Once you get into A-level maths or English or modern foreign languages, and you have potentially a number of people marking different questions, then who is responsible for the marking of that paper? The chief examiners, I know – but they haven’t individually been marking the paper.”

This week’s conference at St Andrews University will also be addressed by Glenys Stacey, head of Ofqual, the exam regulator, which researching exam-marking standards. She is expected to be questioned by headteachers on how the regulator can help improve the situation.

Mr King will also tell headteachers (HMC represents 250 of the UK’s top-ranking independent schools) that he believes they cannot ignore the digital revolution by banning smartphones and tablets from schools. Instead, he argues, teachers should use their ingenuity to allow pupils to make use of their new digital tools to assist their learning.

“Obviously, you don’t want a class where pupils are all fiddling with their devices during the lesson,” he said, “but there are several ways in which you can control this. For instance, you can ask them to hand them in to the front of the class and then allow them to use them when it assists their learning.”

Mr King is also anxious to promote partnerships between the independent and state school sectors. His own school was founded as a co-ed independent day school in 1981, after public pressure for selective schooling following the closure of Leicestershire’s grammar schools.

It has grown from 93 pupils when it opened to 1,250 pupils today. It had to maintain links with the state sector, he said, because a number of the independent schools believed the school was “something of an upstart” and would not play it at rugby. Between 2008 and 2011, though, it was the fastest-growing independent school in the country.

Now, though, it is developing strong links with two state middle schools – Gartree and Manor High – sharing management ideas and teaching expertise, and giving those schools access to some of its facilities, including careers conventions and a swimming pool.

Mr King says of independent school links with the state sector: “I don’t believe we’re in a bad position today – 99.7 per cent of HMC schools currently have partnership agreements with state schools, but they work best where there is a genuine partnership, sharing ideas, not a top-down approach.”

He backs the plan proposed a couple of years ago by Sir Peter Lampl, of the Sutton Trust, for “open access” schools, whereby the Government would fund the places of children who qualify for them but whose parents cannot afford the fees. He suspects its time may come again “if we can sort out the selection issue”. At present, one in three pupils at Leicester Grammar receive financial assistance with the fees.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments