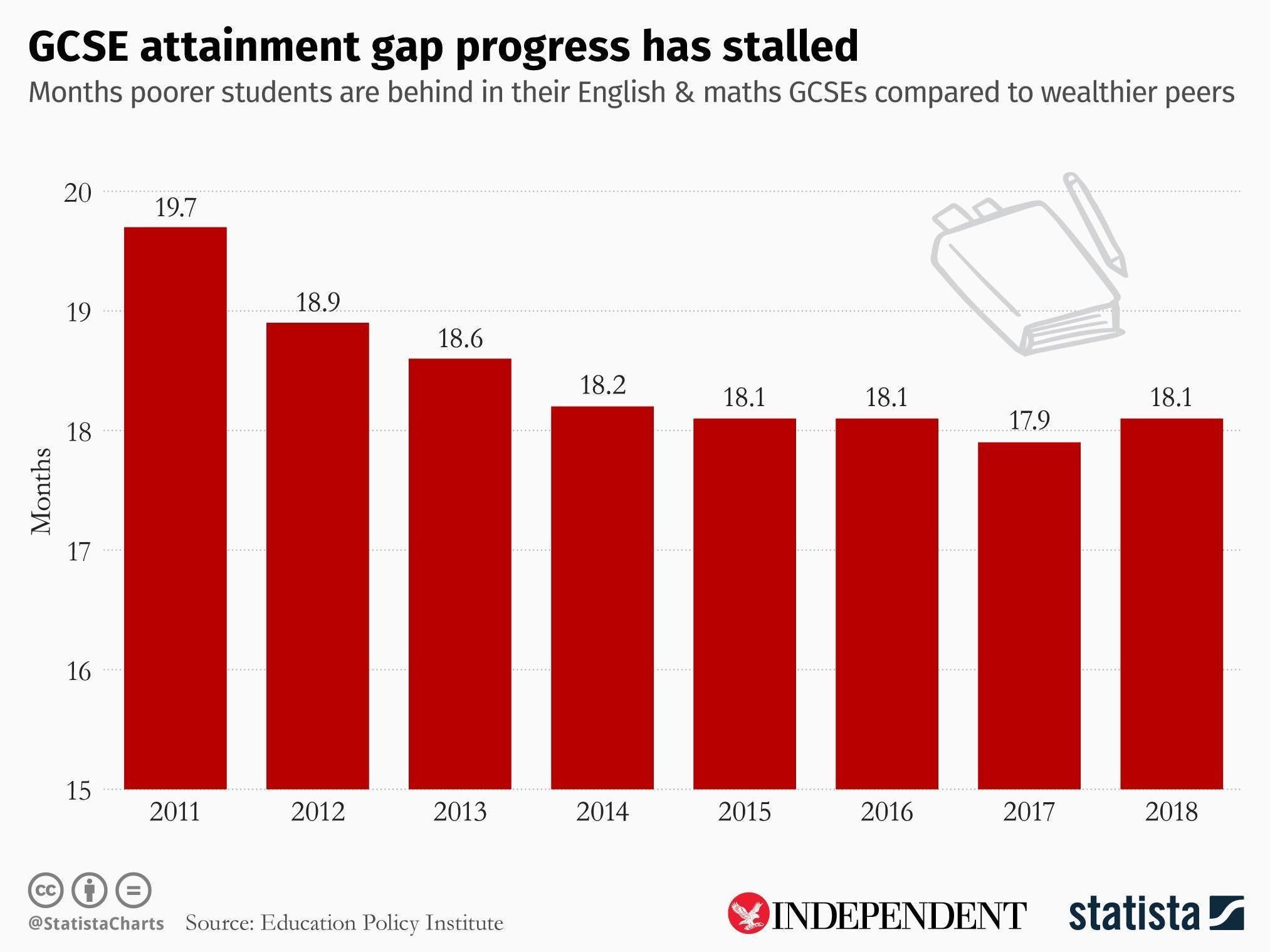

Poorer students ‘18 months behind’ classmates as progress in closing GCSE attainment gap stalls

Austerity cuts hitting secondary schools could be behind the trend, researchers say

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Progress in closing the GCSE attainment gap between poorer pupils and their peers has come to a standstill for the first time since 2011 – and there is a risk of going backwards, report warns.

Disadvantaged students in England are 18 months behind their wealthier classmates in English and maths when they finish their GCSEs, according to the think tank Education Policy Institute.

The attainment gap has widened slightly from 2017 – and if the current five-year trends continues, it could take 560 years to close the disadvantage gap.

It also found that disadvantage gaps are larger and growing in parts of the north of England. In Rotherham and Blackpool, poorer pupils are trailing their peers by more than two years at GCSE.

Meanwhile, Black Caribbean pupils have fallen further behind White British pupils by the end of GCSEs (an additional 2.2 months since 2011), the research shows.

In 2018, when English and maths GCSE results were compared, poorer students were 18.1 months behind in terms of attainment – widening by 0.2 months since 2017.

The report found that the most persistently disadvantaged pupils, those eligible for free school meals for most of their school lives, are nearly two years (22.6 months) behind at the end of their GCSEs – and that gap has increased by 0.4 months since 2011.

Researchers say “austerity measures” are partly to blame for the widening of the gap at GCSE.

However, primary schools continued to narrow the gap by 0.3 months between 2017 and 2018.

“[Secondary] school financial pressures, as well as pressures on local authority children’s services, may be having a dual impact on support for disadvantaged pupils in secondary schools,” the report says.

David Laws, executive chairman of EPI and former Liberal Democrat schools minister, said the report should be a “wake-up call” for the new prime minister.

He said: “We are now witnessing a major setback for social mobility in our country. Recent progress on narrowing the education gap between poor children and the rest has ground to a halt.

“The very poorest children are actually further behind now than they were a decade ago – they are almost two years of learning on average behind other children by the time they take their GCSEs.

“Educational inequality on this scale is bad for both social mobility and economic productivity.”

Julie McCulloch, director of policy at the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL), said: “This report makes for grim reading and should be sounding alarm bells in Whitehall.

“The fact that the gap in GCSE attainment between disadvantaged students and their peers has not only stalled but widened slightly is likely to be the result of severe financial pressures which have forced schools to cut back on the individual support they are able to provide to students, as well as cuts to local services for vulnerable families and young people.”

Nick Gibb, the school standards minister, said the gap between disadvantaged pupils and their peers had “narrowed considerably” in both primary and secondary in recent years.

He added: “We are investing £2.4bn this year alone through the pupil premium to help the most disadvantaged children.

“Teachers and school leaders are helping to drive up standards right across the country, with 85 per cent of children now in good or outstanding schools compared to just 66 per cent in 2010, but there is more to do to continue to attract and retain talented individuals in our classrooms.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments