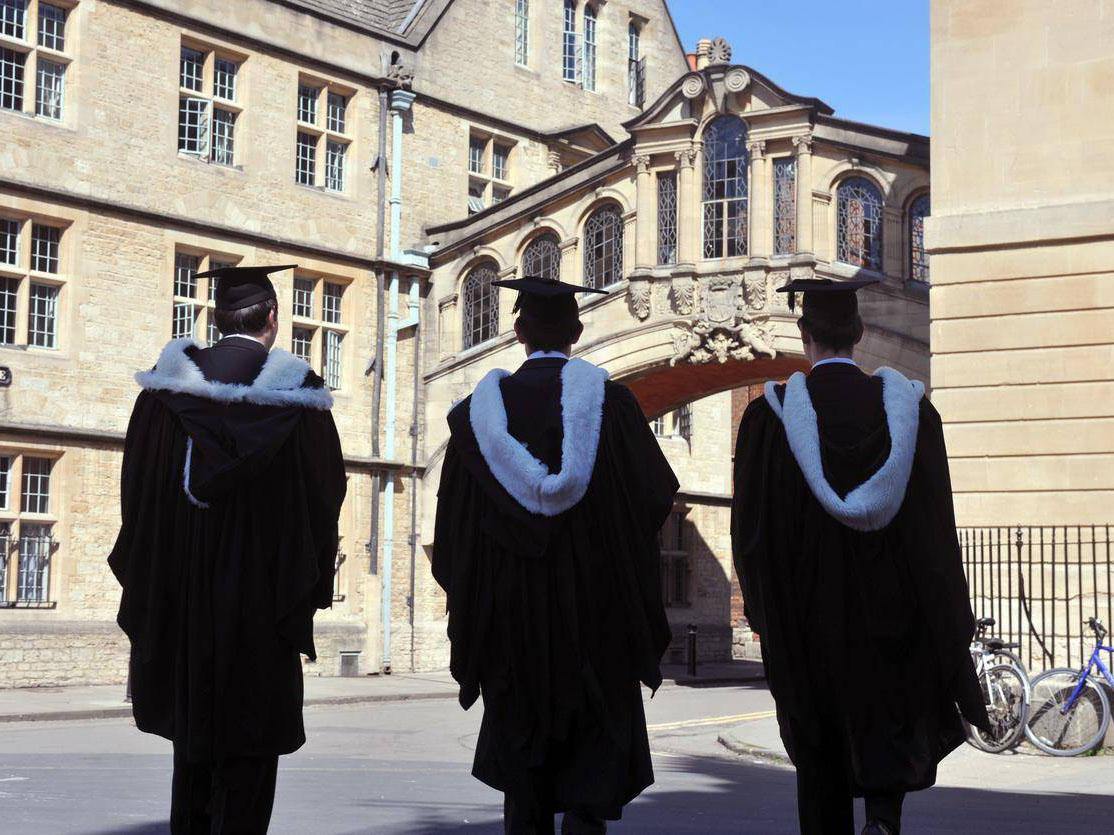

A-level results day: Universities should do more to tackle growing student mental health crisis, Ucas boss says

'Exam stress can be the straw that broke the camel’s back - I am seeing more and more young people suffering from low self-esteem and a lack of a sense of their own abilities'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Universities and Ucas should do more to tackle the growing mental health crisis among students, the leader of the higher education admissions service has admitted.

Clare Marchant, chief executive of Ucas, told The Independent she has seen a rise in the number of anxious students and parents reaching out about “exam stress” in recent years.

She said that universities have a “responsibility” to ensure anxious students leaving school and heading into higher education are at ease to combat mental health concerns.

It comes as tens of thousands of students in England, Wales and Northern Ireland receive their A-level results on Thursday and find out whether they have a place at their chosen university.

On A-level results day last year, there was a 15 per cent rise in calls and social media posts from anxious students and parents to Ucas – from 17,089 in 2016 to 19,709 in 2017.

And they’ve also received more calls from stressed families ahead of this year’s results day, Ms Marchant said.

When asked whether they could do more to tackle mental health problems among young people, she said: “Can the sector do more? Yes. Can we as Ucas do more? Yeah, absolutely.”

With high tuition fees, uncapped student numbers and mental health concerns, it has become a more pressing issue for universities and Ucas to set out realistic expectations for students, she said.

This could include pairing current students with first-year students from similar backgrounds, or holding open days during the week, rather than at the weekend, to give a more accurate picture.

Headteachers and teachers say that rising anxiety and stress among sixth-formers about to enter university could be caused in part by major reforms to A-levels in England.

The reformed A-levels - which have moved away from coursework and returned to exams taken at the end of two years – can feel more “high-stakes” for students, unions have warned.

Last year, the first grades were awarded in the first 13 subjects to be reformed in England and a further 11 reformed subjects will have the first grades awarded on Thursday.

And a survey of secondary school teachers earlier this month, from the National Education Union, found that two-thirds believed changes to the A-levels made students more anxious and stressed.

Alison Roy, from the Association of Child Psychotherapists (ACP), said: “Exam stress can be the straw that broke the camel’s back. I am seeing more and more young people suffering from low self-esteem and a lack of a sense of their own abilities.

“I think that the fear of rejection and of not being accepted is therefore much higher for young people these days.”

Ms Roy added that the pressure to achieve and succeed appears to be more “prevalent” than before, and she said that the influence of social media, as well as the education system, could be to blame.

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL), told said: “Anxiety levels feel to be greater than they were in the past.

“I think a lot of people are going to say why did we need to increase the sense of anxiety through exams that were pushed through very quickly? And has there been a net effect that it has actually increased the anxiety levels of young people and their parents?”

On the universities’ role on student mental health, Mr Barton added: “The sense of continuity you would want of pastoral care – of being there to help a child adjust to becoming a young adult in a very different environment – has been too inconsistent.

“We think universities must pay more attention to the mental wellbeing and socialisation of young people, making sure that support is there. I suspect there is more that can be done there.”

John de Pury, mental health policy lead at Universities UK (UUK), said: “Mental health is a priority for universities. There is already a wide range of support services available and many universities encourage student-led support groups.

“UUK published the Stepchange framework to encourage university leaders to make mental health a core part of all university activities and to improve outcomes for students.

“As students are becoming young adults, taking on the challenges of independent living and moving between their homes and university, they may experience difficulties. We fully support the transition guides from Student Minds.

“Universities have a duty of care to these young adults but we cannot address these complex challenges alone. Partnership working with students, staff, government, schools, colleges, the health services and voluntary organisations is vital if we are to help students to thrive.”

In an effort to address concerns about mental health provisions, universities minister Sam Gyimah announced a raft of new measures in June which are designed to ensure students have adequate support - both before and during their higher education.

“We want mental health support for students to be a top priority for the leadership of all our universities. Progress can only be achieved with their support – I expect them to get behind this important agenda as we otherwise risk failing an entire generation of students,” he said.

“Universities should see themselves as ‘in loco parentis’ – not infantilising students, but making sure support is available where required. It is not good enough to suggest that university is about the training of the mind and nothing else, as it is too easy for students to fall between the cracks and to feel overwhelmed and unknown in their new surroundings.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments