In his Budget speech on Wednesday the chancellor, Rishi Sunak, said that the UK was well placed from an economic and fiscal perspective to deal with the coronavirus crisis.

“As we enter a period of challenge we start from a position of strength,” he told the House of Commons.

“The economy growing, more jobs, higher wages, stable inflation, sound public finances”.

But Labour says that the opposite is the case; that the health emergency is exposing just how badly prepared we are, particularly with respect to our public services.

In his response to the chancellor on Wednesday the leader of the opposition Jeremy Corbyn pointed to a steep fall in NHS beds in recent years, 100,000 staff vacancies and a badly underfunded social care system.

So what’s the reality? Are our economy and public services well prepared or not for this crisis?

What’s the real state of the economy?

The most recent figures from the Office for National Statistics contradict the claim from Mr Sunak that the economy is growing.

The ONS reported on the very morning of the Budget that there was zero growth in GDP in the three months to January.

But it’s true that the employment rate currently stands at a record high (76.5 per cent) and the unemployment rate (3.8 per cent) is at its lowest since the 1970s.

And wages? Average inflation-adjusted wages finally crawled above their pre-crisis peak last year. But they are not growing strongly.

The ONS reported that they grew at an annual rate of 1.4 per cent in the final quarter of last year – well below pre-2008 average growth rates of 2.4 per cent.

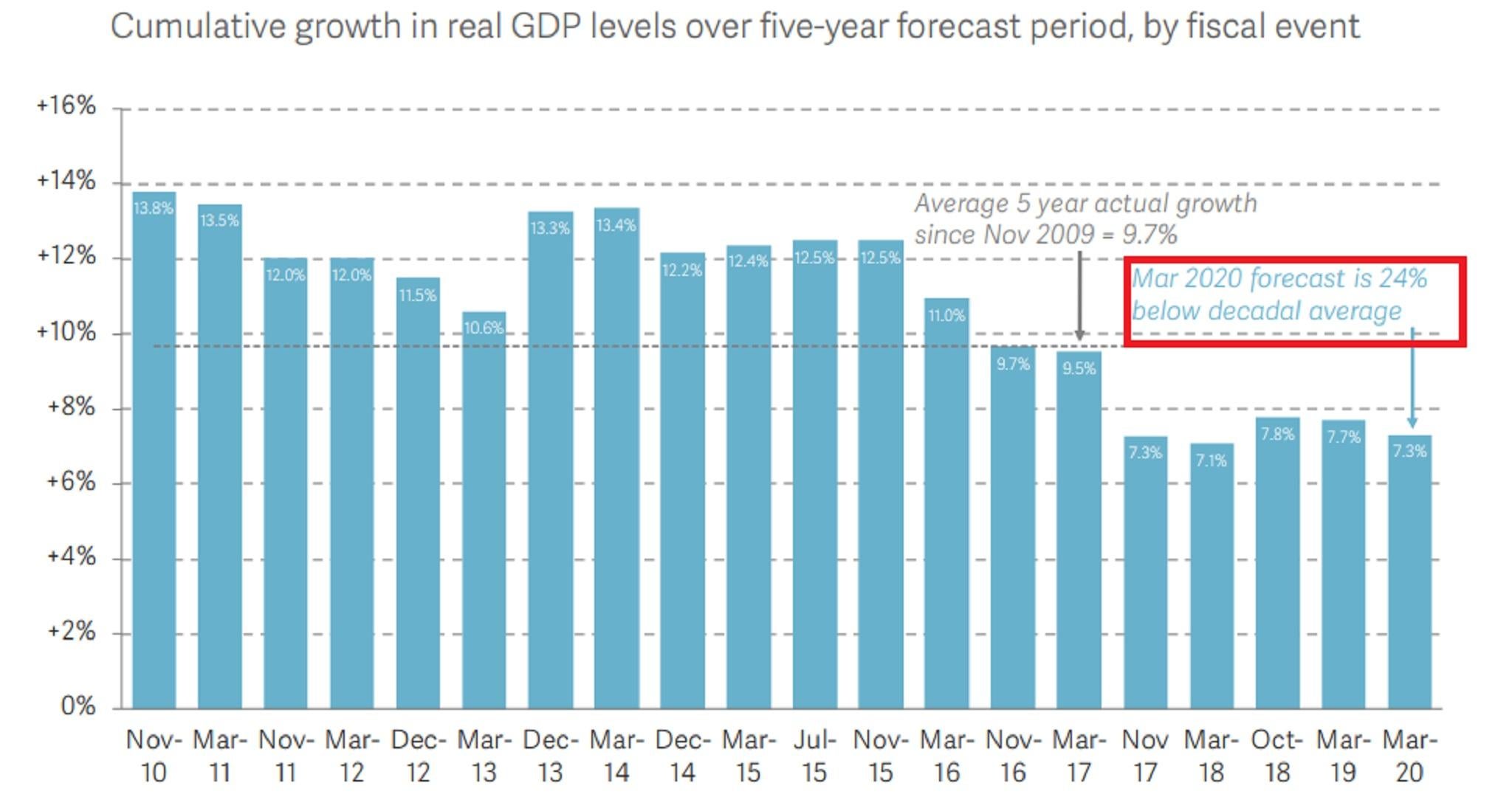

And looking forward, the five-year GDP growth forecast from the Office for Budget Responsibility, published alongside the Budget, was the second weakest it has ever produced, with an expansion of just 7.3 per cent pencilled in.

“That is not a robust position for coping with shocks like the coronavirus,” says Paul Johnson, the director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

But isn’t the deficit down a lot?

That’s certainly true. The state deficit peaked at 10 per cent of GDP in 2009-2010, around £158bn.

In 2018-19 the UK government borrowed only 1.8 per cent of GDP, or £38bn.

“The public finances considering where they were a decade are in not a bad position for raising more money if you have to,” says Mr Johnson.

“Borrowing last year was relatively low. We’re paying very small amounts in interest payments. It’s pretty clear that if we wanted to borrow a bunch more money to deal with coronavirus the markets are going to lend it to us for not very much. So in that sense there is robustness.”

What about public services though?

Inflation-adjusted spending on the NHS increased through the years of austerity, as a “protected” area of spending.

But that increased spending did not met rising demands from an ageing population.

The King’s Fund think tank estimates a shortage of around 100,000 full-time equivalent staff across NHS Trusts.

As for social care, local authority spending on that fell by 8 per cent between 2010 and 2017, creating severe knock-on impacts on the health service.

“Clearly we’ve had a period where there’s been tight, by historic standards, spending on the NHS. That’s going to mean there’s less spare capacity than there otherwise would have been,” Mr Johnson says.

But isn’t the NHS getting a lot more government money to cope?

Rishi Sunak unveiled £5bn for the NHS as part of a Covid-19 response fund on Wednesday.

He also said more could be made available. “Whatever it needs, whatever it costs, we stand behind our NHS,” Mr Sunak said.

But Mr Johnson warns that it’s not as simple as turning on the spending taps.

“Making £5bn available for public services this year is a different story to those public services then being able to use that money effectively – finding the doctors, nurses, care workers or hospital beds,” he said.

“It’s easy for the chancellor to stand up and say this [but] it’s going to be pretty tough to adjust quickly.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments