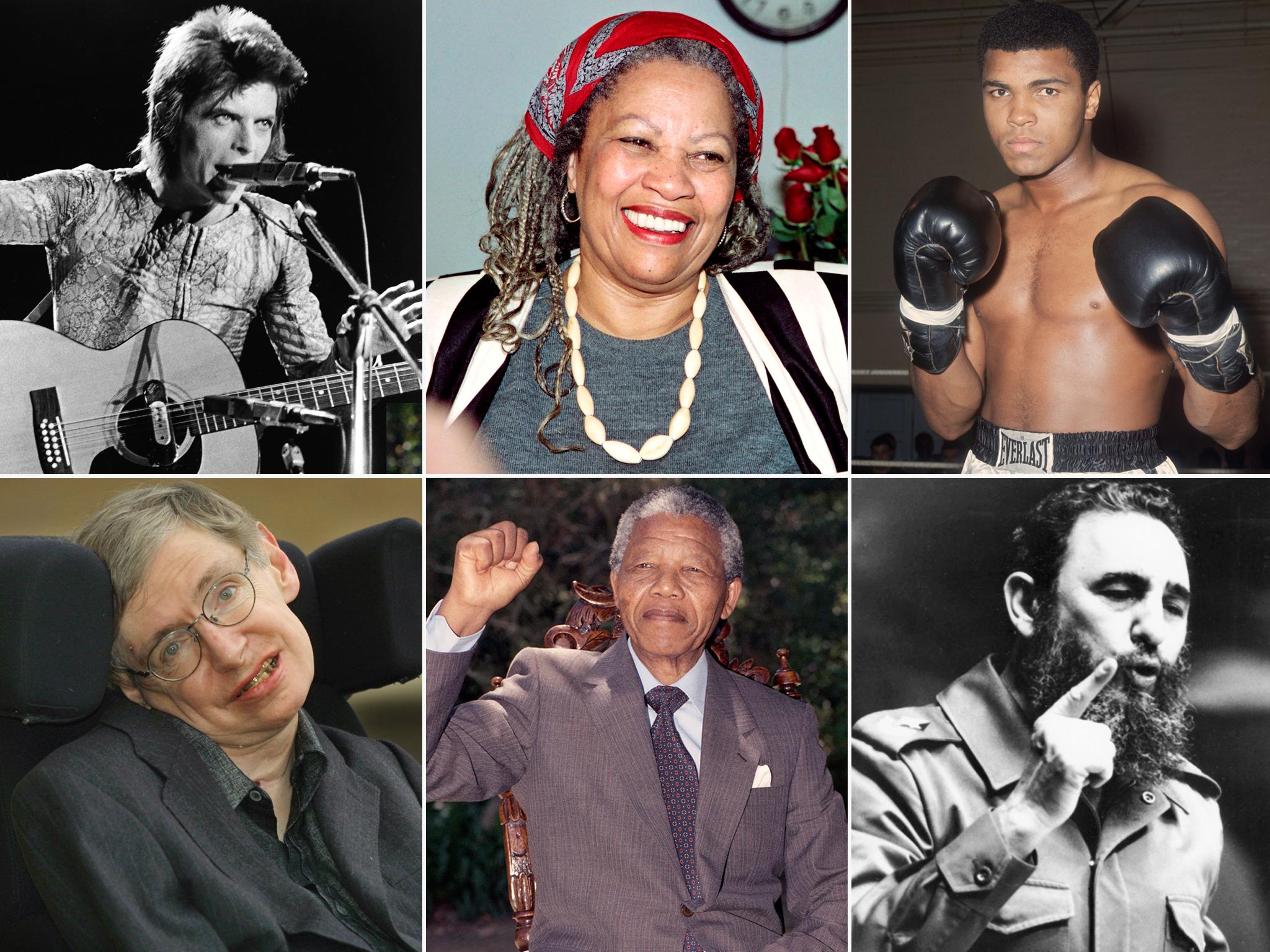

Larger than life: Remembering the people we lost in the 2010s

The leading lights in their fields, these figures had an impact that will reverberate for a long time

The 2010s was the decade we said farewell to some of the largest characters on the world stage, figures such as Nelson Mandela, who did more than anyone to transform the political landscape of South Africa and the wider region; Stephen Hawking, the cosmologist who revolutionised our understanding of the universe; David Bowie, whose aesthetic vision has arguably shaped modern-day culture more than any other individual; and Toni Morrison, whose fiction about America’s shameful history of racism shook up the literary canon.

Here is our selection, culled from the obituary pages of The Independent, of those who left us in the past decade but whose influence will live on.

Stephen Hawking: physicist who was light years ahead of the Nobel prize

Died 14 March 2018

Stephen Hawking was one of the most imaginative and influential physicists of his generation yet he never won the Nobel prize. He wrote a popular science book that became a publishing sensation, which is arguably the least-read bestseller of all time.

He was cruelly confined to a wheelchair by a disease that progressively paralysed him yet his mind ranged freely across the immensities of the cosmos. These are just some of the paradoxes of what, by any standards, was an extraordinary life.

He became an international phenomenon, the best-known and most recognisable scientist on the planet. What caught the public imagination was the contrast – the man paralysed in a wheelchair whose mind wrestled with the biggest mysteries of the universe, everything from the nature of black holes to difficulties of time machines to the origin of the universe. Since 1979, Hawking had been the Lucasian professor of mathematics at Cambridge, a chair previously occupied by Newton and Charles Babbage, the father of the computer.

His book A Brief History of Time (1988) was a publishing phenomenon: by May 1995 it had been in the Sunday Times bestseller list for a record 237 weeks, a feat which earnt it an entry in The Guinness Book of Records.

Hawking’s mechanical voice – he had lost his voice after an emergency tracheostomy in the summer of 1985 saved his life – was instantly recognisable across the world. In 1993, he appeared in Star Trek: The Next Generation as a hologram of himself, playing poker with Data and holograms of Newton and Einstein (he is the only person to have played himself in a Star Trek film). He appeared in The Simpsons Halloween special in 1995, with Homer Simpson saying: “There’s so much I don’t know about astrophysics. I wish I read that book by that wheelchair guy.”

The publicity magnified in the public’s imagination Hawking’s scientific achievements. Nevertheless, his contributions are important. The reason he did not received the Nobel prize is that the Nobel committee like to see supporting observational or experimental evidence of theories. Although black holes litter the universe, with every galaxy, including our own Milky Way, harbouring a “supermassive” version in its heart, no one has ever seen Hawking radiation.

Nevertheless, people are building black hole analogues in laboratories around the world, uncrossable boundaries that mimic a black hole horizon. It is only a matter of time before Hawking radiation is seen on Earth. A case, if ever there was one, for a posthumous Nobel prize? Marcus Chown

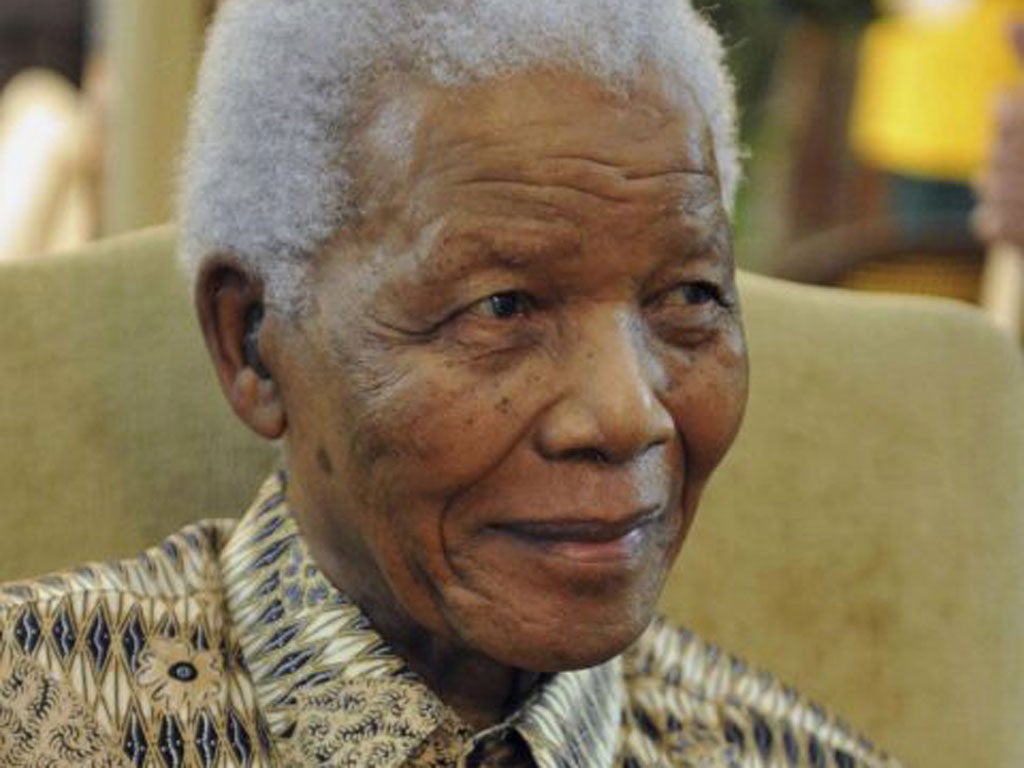

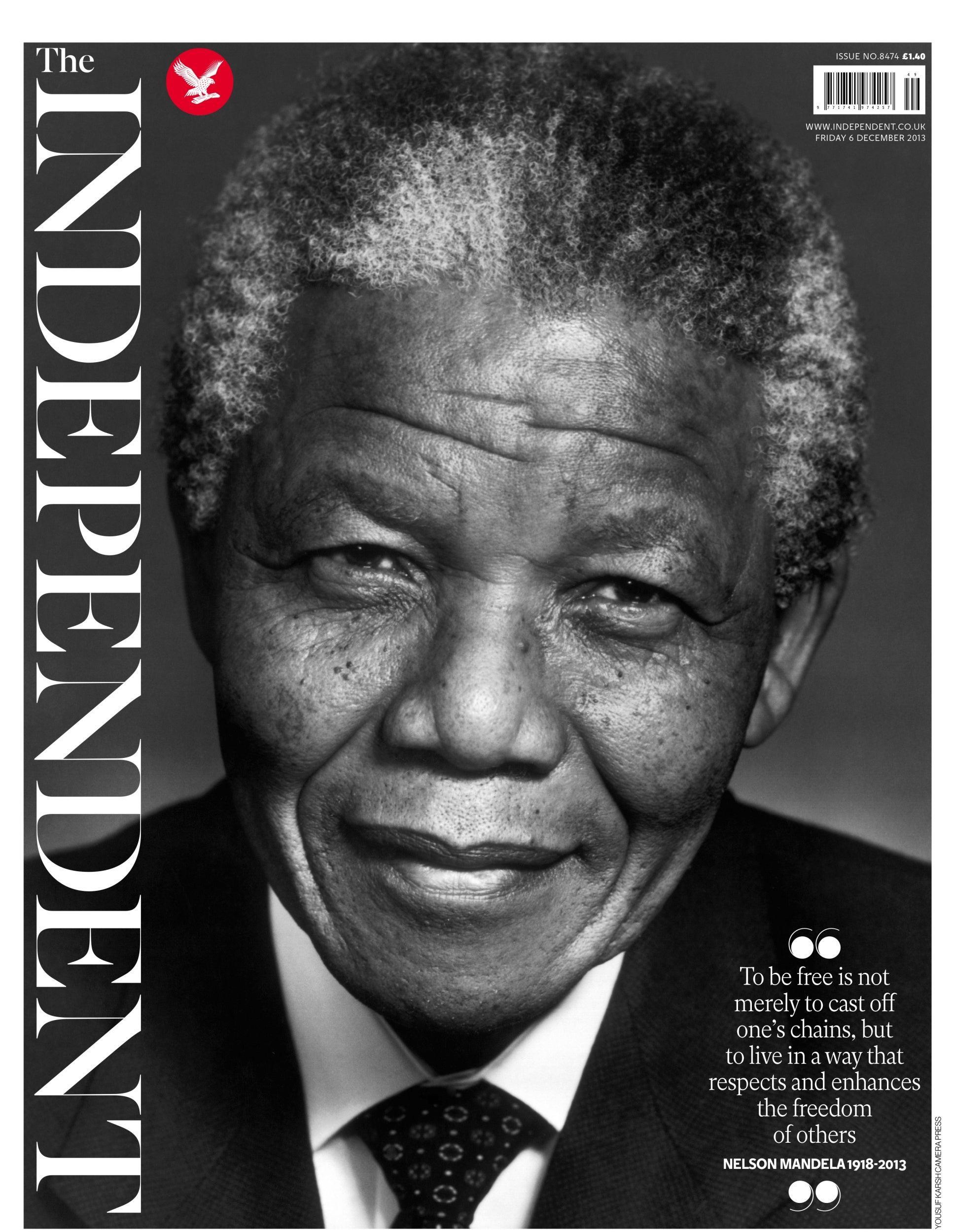

Nelson Mandela: the father of South African democracy

Died 5 December 2013

“Rwanda is our nightmare, South Africa is our dream.” So wrote the Nobel prize-winning African novelist Wole Soyinka in 1994. It was just a month after two events which seemed to span the polarities of despair and hope so many saw in the continent of Africa in the post-independence era.

In Rwanda a million people had died in a ghastly genocide. But South Africa had made an astonishingly peaceful transition from oppressive white rule to a black-majority government elected in the country’s first free elections ever – and it had done so under the guidance of one extraordinary man.

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela embodied not only enormous political sagacity but also an almost saintly capacity for magnanimity, forgiveness and reconciliation. Despite 27 long years in jail at the behest of his white enemies his conduct and temperament, both inside and when he was eventually freed, earned him an unparalleled moral authority among blacks and whites alike.

His very name ought to have given a clue to the background and influences which formed him as one of the seminal figures of 20th century history. His forename was Rolihlahla – which in the tongue of his native Xhosa tribe means “troublemaker”. His family name, Mandela, like his clan name, Madiba – which became the affectionate term by which he was known in his later years as father of his nation – revealed him to be a member of the family of the paramount chief of the Thembu people.

Mandela was inaugurated as president on 10 May 1994 in a government of national unity with his predecessor as president, FW de Klerk, as his first deputy and Thabo Mbeki as his second. In his inaugural address he said: “Never again shall it be that this beautiful land will again experience the oppression of one by another.” Making those words real was a formidable task.

His first year gave an indication of the breadth of vision and boldness he brought to it. He sent out sophisticated signals. Though he began to wear African batik shirts, even on formal occasions, he also donned the jersey of the Springbok rugby team, a previously hated symbol among blacks, for the 1995 Rugby World Cup – a gesture widely seen as a major step in the reconciliation of white and black – and he wore it again as he presented the trophy to the victorious Springbok’s Afrikaner captain Francois Pienaar. He sacked Winnie Mandela from her cabinet post, following allegations of corruption, took tea with the widows of white politicians and flew to the white enclave of Orania to visit the widow of Hendrik Verwoerd, the primary architect of apartheid.

His life was an inspiration throughout the world, to all who are oppressed and deprived, and to all who oppose oppression and deprivation. He was a model of faith, hope and charity. There was about him, something to which the world aspired. It was as if we saw ourselves dimly reflected in his glory. Through his chains it was as if we were all enslaved, and through his extraordinary magnanimity he freed the world. Paul Vallely

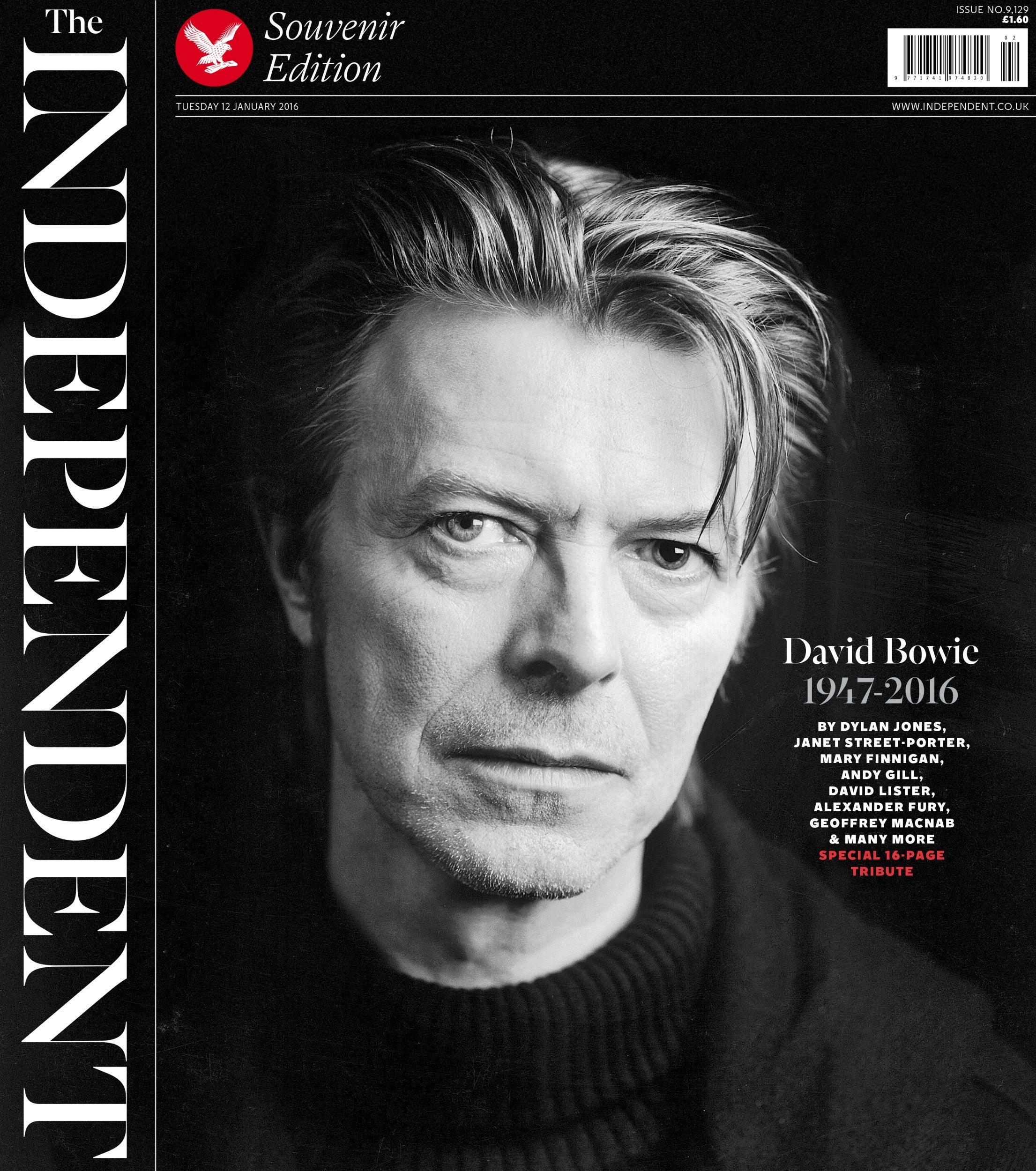

David Bowie: visionary singer and songwriter who for five decades exerted unparalleled influence

Died 10 January 2016

Today it is hard to conceive of the colossal impact made in 1972 by David Bowie in his guise of Ziggy Stardust. The fan hysteria generated by this futuristic character with his prophecies of Armageddon, and the tour that promoted the album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, was on a scale unseen since Beatlemania almost 10 years previously. By July 1973 Bowie had five albums in the British Top 40, three of them in the Top 15.

Bowie’s rise to a kind of immediate superstardom was so instant that it seemed as though this was precisely the kind of new rock’n’roll star, simultaneously androgynous and asexual, that unconsciously had been eagerly anticipated. “The man is a stone genius,” effused New York’s Village Voice, in the parlance of the times, “and for those who have been waiting for a new Dylan, Bowie fits the bill. He is a prophet, a poet – and a vaudevillian. Like Dylan, his breadth of vision and sheer talent could also exercise a profound effect on a generation’s attitudes.”

Always useful in capturing a previously unknown base audience, Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust persona also spearheaded a new rock’n’roll movement, glam rock. Although he didn’t publicly admit to bisexuality until 1974, it hardly came as a surprise: he had promoted his 1971 album The Man Who Sold the World while wearing a dress; and despite the presence of his wife Angie was widely believed to have had affairs with both Marc Bolan and Mick Jagger – which turned out to be true. The trouble with David Bowie, however, was that it was hard to separate any of his activities from a scent of calculation that seeped into all he did: ultimately there was always something cold at the core of even his greatest work.

Yet who could possibly have anticipated the success that came with Ziggy Stardust and its follow-up Aladdin Sane four years previously when he enjoyed his first chart entry – which seemed to characterise him as a one-hit-wonder – with the enigmatic “Space Oddity”? Yet if you listened to the words of that first hit, it was revealed as an extraordinary piece of work, hardly a song at all: the saga of Major Tom floating out of control in his space capsule above Earth.

The work revealed Bowie’s art school background, as well as a psyche born out of a family with a considerable history of mental health problems; after being diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic, Terry, his half-brother, had been institutionalised (early in 1985 Terry died by suicide), and three aunts were similarly troubled: Bowie always feared that such sickness might emerge within him. Major Tom was merely the first of a sequence of identities adopted by Bowie that could be seen as a long journey to discover his true self. Chris Salewicz

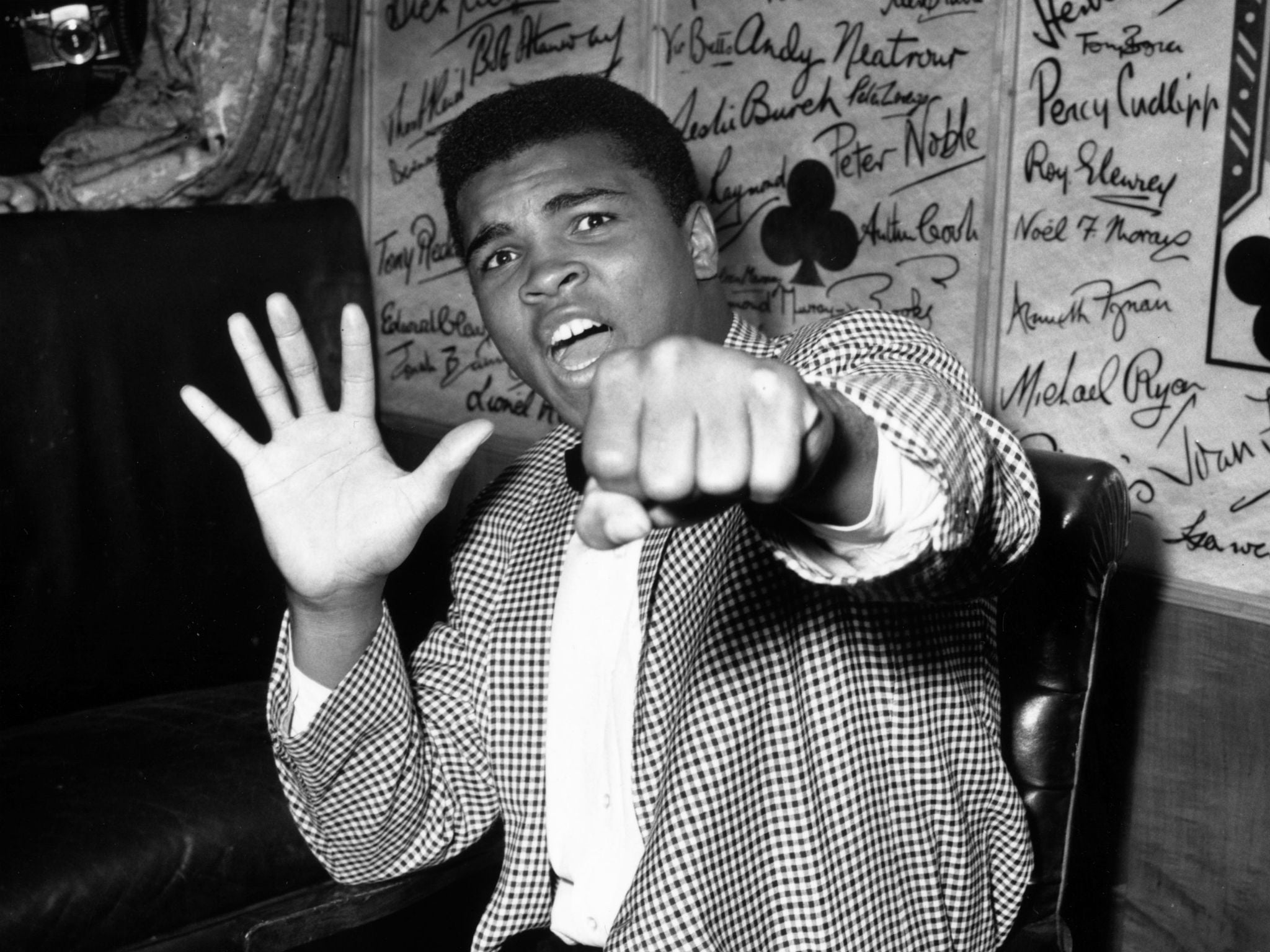

Muhammad Ali: one of the greatest fighters who ever lived – and a good man

Died 3 June 2016

To a whole generation of young men, Muhammad Ali was more than a boxer, more than a sportsman. He was freedom of spirit personified. His outrageous defiance of the rules, his sense of mischief, his unswerving belief in social justice, all fitted the mood of his times.

It was the most horrible of ironies that Ali, once so young, so gifted and so downright noisy, should spend his last years trapped in a mask which allowed him to speak only in mumbles and whispers.

That Ali of all people should have ended like this was cruel, yet somehow, just as he had done so many times inside a boxing ring, he found a way to turn the circumstances to his advantage. When boxing was finally prised out of his reluctant system, to be replaced by Parkinson’s syndrome, he settled down to live the rest of his days with discipline and dignity. He accepted his disability as a positive part of his human “journey” and he set out to fulfil the missionary purpose he felt was a part of his Muslim faith.

Ali was beyond question the best heavyweight of his generation. At 25 he was still only coming to his peak. As great as he was, nobody knows how much greater he might have been. By the time of his fight with Zora Folley in March 1967, Ali’s objection to fighting in the Vietnam War was known. In a radio phone-in, he had already said: “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong.” And when the call to make the symbolic step forward came in April 1967, he stood still. In June 1967 he was sentenced to five years in jail and fined $10,000 – the maximum punishment the system would allow – for refusing to be drafted. His passport was confiscated. In what now seems an astonishing reaction, Ali was also stripped of his world title and banned from fighting by every state in the US.

Unable to box, Ali took to lecturing at American universities, where opposition to the war was high. He didn’t serve a day in jail, but admitted, “I am just about what they call broke.” His popularity on the angry campuses of the United States rocketed, however. He made people think – and he made them laugh. “Now, I’m sure there’s a heaven in the sky and coloured folks die and go to heaven,” he said. “But where are the coloured angels? They must be in the kitchen preparing the milk and honey.”

Today’s boxers owe Ali a great debt. He took the sport off the back-burner and made it a frontline sport again. And he lived out his youth at a very special time, when to be born black, especially in the southern states of America, meant a terrible struggle for dignity and respect. Ali made that struggle easier for millions of people, not just black and not just American, all over the world.

He was a great fighter, one of the greatest who ever lived. But beyond that he was a good man. Millions across the world will remember him with immense fondness. Bob Mee

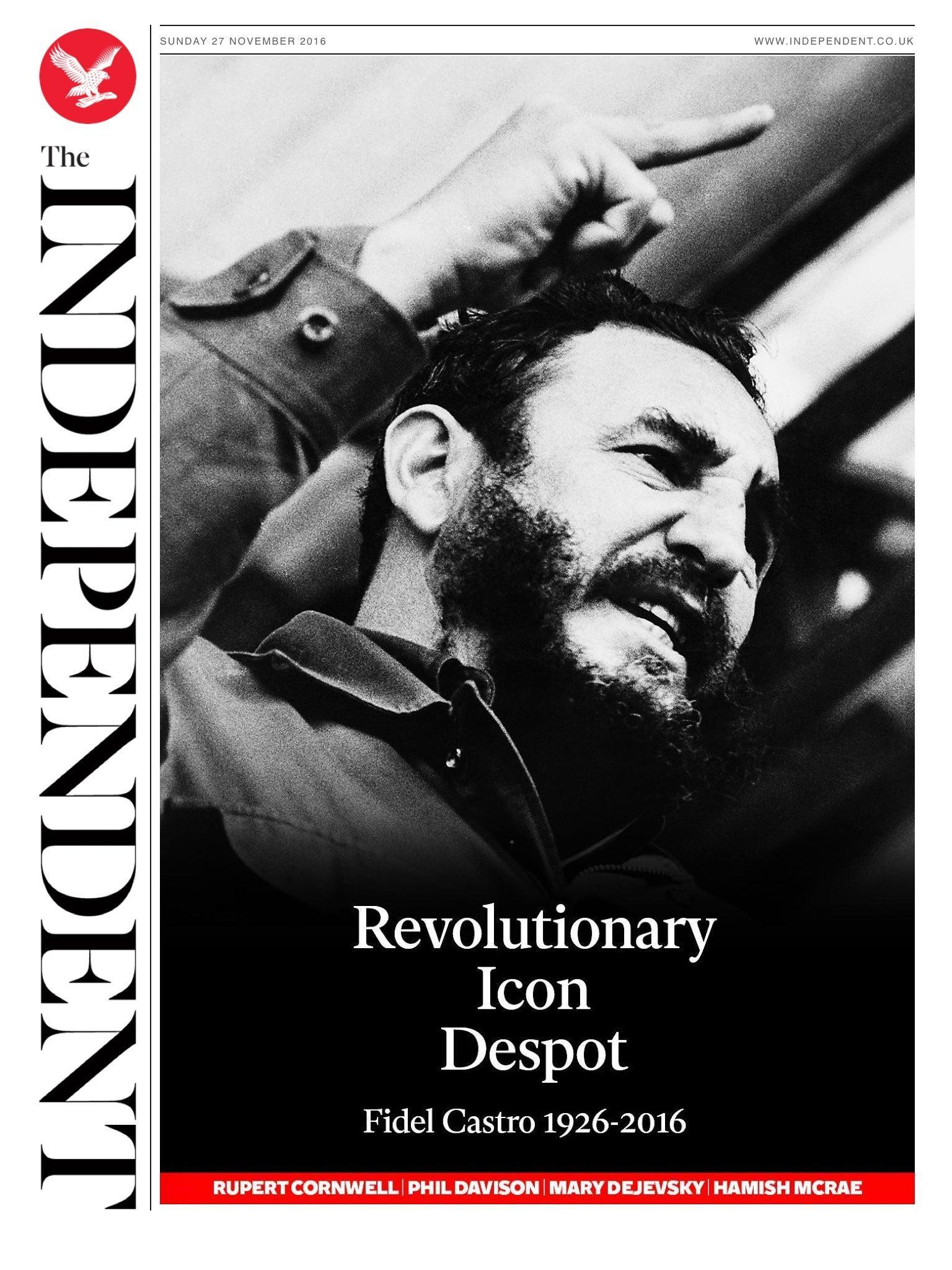

Fidel Castro: the Cuban revolutionary who defied 10 US presidents

Died 25 November 2016

During half a century in power, Fidel Castro faced down no fewer than 10 US presidents, despite the fact that his Caribbean island is only around 90 miles from Florida. He died just two months before the fascinating prospect of a new relationship, for better or worse, between communist Cuba and US president-elect Donald Trump. Whether you loved him or hated him – and there were few in-betweens – Castro was the world’s longest-serving political leader before he stood down and handed over de facto power to his brother Raul in 2008. Even thereafter, there was never any doubt as to who was calling the shots.

Best remembered by his olive fatigues, trademark military cap and (until forced to give them up for health reasons in 1985) his giant Cohiba cigars, he liked to be addressed as Comandante (Commander) but was officially known as el Jefe Maximo (the Maximum Leader).

Few people on his island, not even its dissidents, ever lost the habit of referring to him simply as “Fidel”. Ruling initially over only 6 million people (rising to 11 million), he billed himself as David to the Goliath across the Florida Straits, and became a giant on the world geopolitical stage.

He and his Argentinian comrade Ernesto Che Guevara, both bearded and handsome, became heroes to a generation or more, their revolution setting the tone for the 1960s as posters of the two sprouted on student bedroom walls around the world. They became spearheads of change, particularly throughout a Latin America dotted with dictatorships.

Ironically, Castro might have gone on to fulfil his promise of democracy for Cuba had it not been for American paranoia and an overreaction to his success, initially from President Dwight Eisenhower, who pledged to bring the young upstart down.

At the time of the revolution, Castro was not, at least openly, a communist and had never preached Marxist-Leninism, or even socialism. It was a further two years before, prodded by US antagonism, he declared himself a communist and began turning his island into a one-party state modelled on the Soviet Union.

Castro will always be the man who, backed by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, brought the world to the brink of a third world war, a potentially cataclysmic nuclear one. Soviet nuclear missile-launching pads had been spotted on Cuba by an American U-2 spy plane, the missiles pointed towards the US. For most of those 13 days in October 1962, the three players – Castro, Khrushchev and John F Kennedy – held world peace in their hands.

Most Cuban exiles despised the Cuban leader; most democratic governments opposed and isolated him; and each of those 10 US presidents sought to undermine him to varying degrees, at least until President Barack Obama sought some kind of detente. What would have happened with Fidel Castro alive and Donald Trump in the White House, we will now never know. The one thing certain is that it would have been interesting. Phil Davison

Toni Morrison: Nobel laureate who transformed American literature

Died 5 August 2019

Toni Morrison conjured a black girl longing for blue eyes, a slave mother who kills her child to save her from bondage, and other indelible characters who helped to transfigure a literary canon long closed to African Americans.

Morrison spent an impoverished childhood in Ohio steel country, began writing during what she described as stolen time as a single mother, and became the first black woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature. She placed African Americans, particularly women, at the heart of her writing at a time when they were largely relegated to the margins both in literature and in life. With language celebrated for its lyricism, she was credited with conveying as powerfully, or more than perhaps any novelist before her, the nature of black life in America, from slavery to the inequality that went on more than a century after it ended.

Among her best-known works was Beloved (1987), the Pulitzer-winning novel later made into a film starring Oprah Winfrey. It introduced millions of readers to Sethe, a slave mother haunted by the memory of the child she had murdered, having judged life in slavery worse than no life at all. Like many of Morrison’s characters, she was tortured, yet noble: “Unavailable to pity,” as the author described them.

Beyond her own literature, Morrison was credited with giving voice to black stories through her work as a Random House editor, beginning in the late 1960s. There was a “terrible price to pay”, she once remarked, for leaving the comfortable familiarity of Lorain, the Ohio town where she had grown up, for a career in an unwelcoming white society. But she wanted to participate in the creation of a “canon of black work”, she said. While raising two sons, and while pursuing her own writing in the hours before dawn, she shepherded into print works including autobiographies of the boxer Muhammad Ali and the political activist Angela Davis.

Morrison also helped to anthologise the writings of African authors including Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka. She oversaw the publication of The Black Book (1974), a bestselling documentation of black life in America that included advertisements for the sale of slaves, photographs of lynchings, and images of churches and other spiritual places that had helped sustain black communities.

Beloved was praised as one of the most significant works of the century. In 1988, 48 black writers – among them Maya Angelou, Alice Walker and Ernest J Gaines – placed an open letter in The New York Times protesting about the fact that Morrison had not yet received the National Book Award or the Pulitzer Prize. That year, the Pulitzer went to Beloved. In 1993 came the Nobel.

“I wanted to translate the historical into the personal,” Morrison said of the book. “I spent a long time trying to figure out what it was about slavery that made it so repugnant, so personal, so indifferent, so intimate, and yet so public.”

For all the exploration of race in Morrison’s works, one of her most enduring messages was delivered through its absence. In Paradise (1997), Morrison forced readers to guess which character was the white woman whose murder is foretold in the book’s first words. “I did that on purpose,” Morrison said. “I wanted the readers to wonder about the race of those girls until those readers understood that their race didn’t matter. I want to dissuade people from reading literature in that way. Race is the least reliable information you can have about someone. It’s real information, but it tells you next to nothing.” Emily Langer © Washington Post

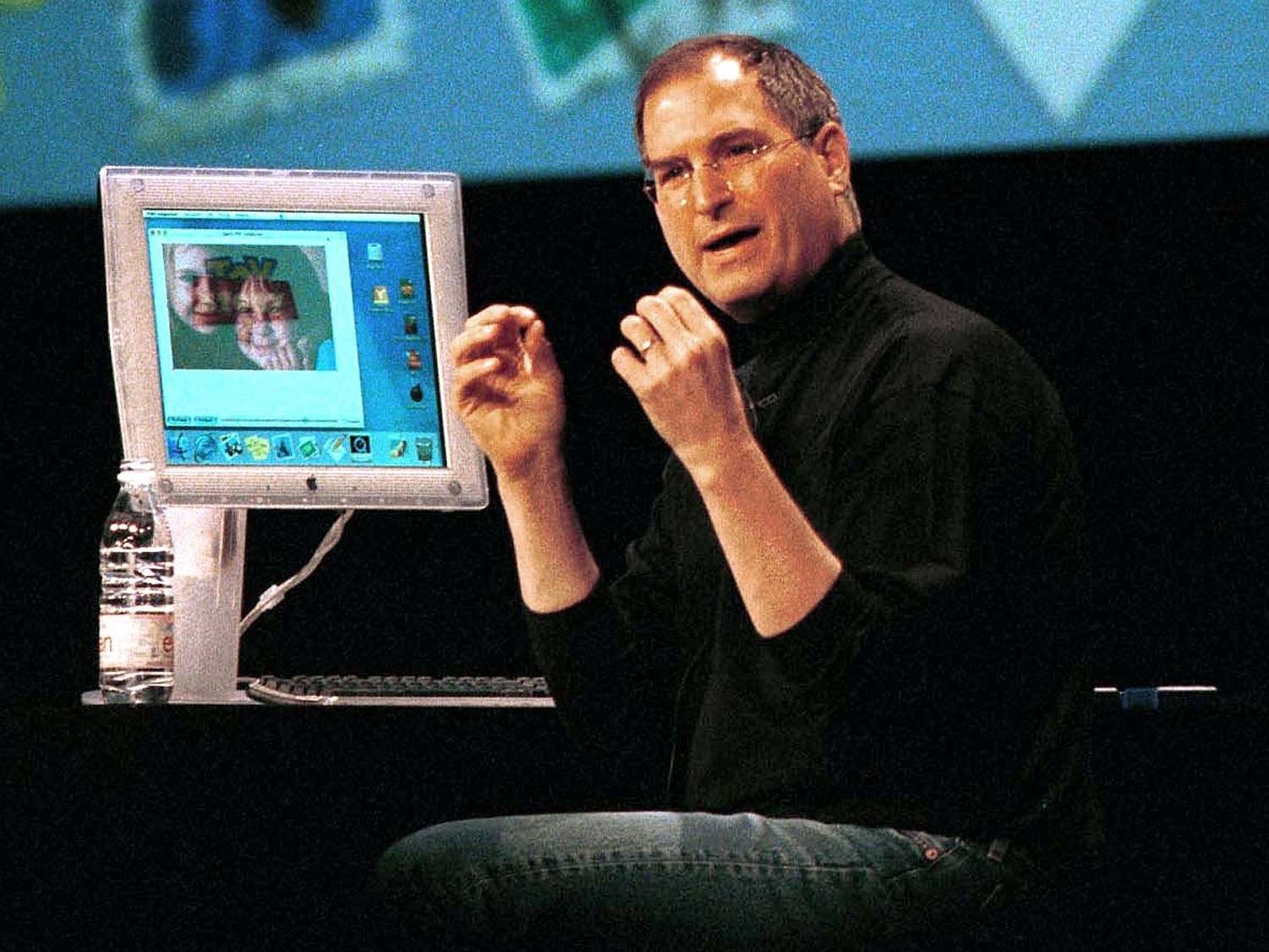

Steve Jobs: Apple co-founder hailed as one of the most important pioneers of the computing age

Died 5 October 2011

Steve Jobs, the co-founder of Apple Computers, was an inspirational and pioneering innovator who emerged at the dawn of the present age of computers, the internet and the electronic music revolution. His unique mix of personal characteristics made him pivotal to the rapid evolution which in recent decades created such extraordinary changes in the workplace and in the social habits of many millions.

He made mistakes and he made enemies. He dropped out of university and once got sacked from the company he set up. But he was indisputably one of the outstanding founding fathers of the modern computing and electronic era. He achieved breakthroughs by employing the vision which made him one of the secular demi-gods of the electronic age. In his products and his person he was one of the coolest of the cool.

He was idolised by many computer enthusiasts though much disliked by his detractors. But his computers, and later his phone and music technology, were eagerly sought after and sold in their millions. Their attraction was that they transcended the mundane level of mere usefulness to soar into the realms of the must-have.

Bill Gates’s Microsoft was a far bigger enterprise, but it was Apple that caught the imagination with its more stylish design. Jobs pored over every apparently inconsequential detail. He took things from the utilitarian to the aesthetic, projecting his inventions as the height of individuality. In a sense he personalised the personal computer. “The thing that bound us together at Apple was the ability to make things that were going to change the world,” he enthused. “We all worked like maniacs and the greatest joy was that we felt we were fashioning collective works of art.”

Jobs was a new type of technological entrepreneur for a new generation. He elevated the image of computers from that of functional gadgets into that of vital lifestyle accessories. What Microsoft produced was immensely useful but what Jobs and Apple exuded was a wow factor which captivated millions. He boasted: “Woz [Steve Wozniak, Apple co-founder] and I worked hard, and in 10 years Apple had grown from just the two of us in a garage into a $2bn company with over 4,000 employees.” Jobs was 30 years old.

Jobs pulled no punches in scoffing at competitors. “The only problem with Microsoft,” he jibed, “is that they just have no taste. I don’t mean that in a small way. I mean that in a big way, in the sense that they don’t think of original ideas and they don’t bring much culture into their products.”

He was not the mellowest boss in the world, at times inspirational but at others calling employees stupid, according to one of his many biographers. He was also said to be sometimes too persuasive, employing his salesmanship to overpower arguments even when he was in the wrong. His skills were said to create a “Jobs reality distortion field”.

Steve Jobs will be remembered as one of the most important pioneers of the modern computing age. He was a phenomenon who emerged from the sub-culture of the hippie to become a yuppie. He developed into a sometimes bullying boss but above all into a unique figure – part entrepreneur, part auteur – who helped to shape the modern electronic age. David McKittrick

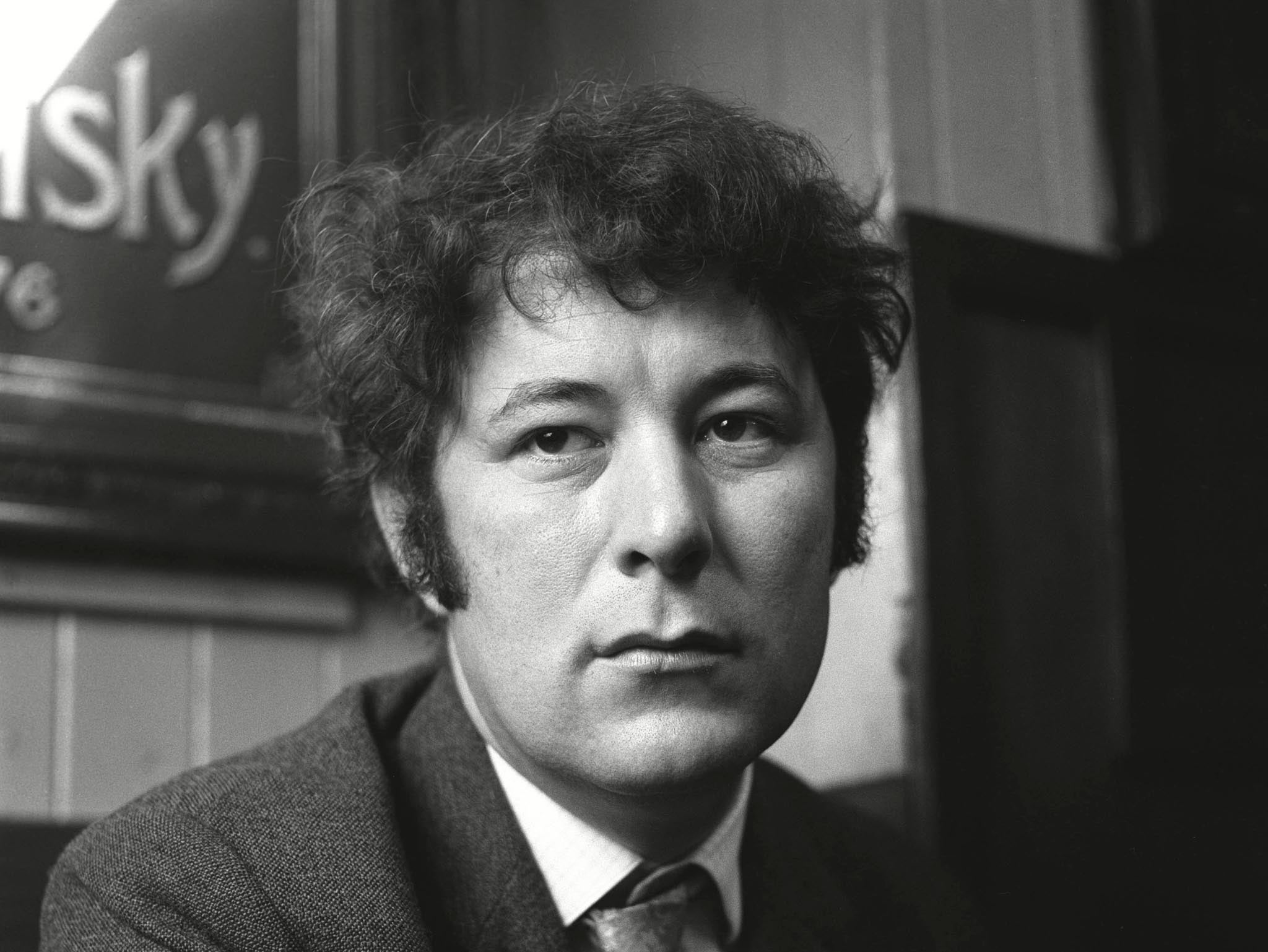

Seamus Heaney: Nobel prize-winning Irish poet with his own vision of the world

Died 30 August 2013

Seamus Heaney was probably the best-known poet in the world. He is irreplaceable, and for his many friends and admirers there will be a tremendous sense of private as well as public bereavement.

In his Nobel prize acceptance speech, delivered in Stockholm in 1995, Heaney recalled his first encounter with European languages via the radio in the kitchen of his wartime Co Derry home. Overhearing fragments of foreign sentences, he said, as the dial was moved from one accustomed station to another, “I had already begun a journey into the wideness of the world. This in turn became a journey into the wideness of language, a journey where each point of arrival – whether in one’s poetry or one’s life – turned out to be a stepping stone rather than a destination, and it is that journey which has brought me now to this honoured spot.”

In the same speech, with his customary felicity, Heaney paid tribute to his great predecessor WB Yeats, to whom he had inevitably been compared as far back as the 1970s, when his astonishing career was just beginning to get into its stride. His fourth collection, North (1975), was a stepping stone on the way to his ultimate status as the “greatest living poet” – the most widely read poet in English, possessor of incomparable gifts and impeccable instincts, and all the other superlatives heaped on him.

North was held by some to denote an artistic breakthrough, embodying as it did a new strength and sophistication following on from the pared-down, rural, evocations and intensities of the earlier collections. In Heaney’s native Northern Ireland, though, its reception was less than adulatory. There were complicated reasons for this: for example, with the Troubles entering a horrific phase, it was felt that certain poems in the collection could be read as an endorsement of Republicanism, with Heaney displaying, at best, as one critic wrote, “a culpable ambiguity in [his] responses to atrocity”.

Such reservations were based on a misreading: Heaney was never an apologist for violence, despite the seeming drift of the much-quoted lines about “conniving” in civilised outrage, while understanding “the exact and tribal, intimate revenge”. His brief was large enough to accord a right of expression to every variety of belief. And if “the dark matter of the news headlines” got into Heaney’s poetry, as it did at intervals from this time on – though always contained within an oblique and subtle, multi-layered and illuminating, modus operandi – the light he was aiming for, he said, “was the kind that derives from clarity of expression, from plain speaking”. Patricia Craig

Neil Armstrong: Astronaut and scientist who became the first man on the moon

Died 25 August 2012

Few people leave such a lasting imprint on human history that they are raised to the status of immortality, but, much to his distaste, Neil Armstrong was one of that select band. His televised exploits during one week in July 1969 elevated him above his fellow astronauts and test pilots to the rank of superhero, an internationally renowned figure whose name would resound throughout the ages.

The wheel of fortune decreed that Armstrong was in exactly the right place at the right time, but he had earned the right to rewrite the history books by becoming the first man to walk on the moon. His entire life leading up this ultimate challenge had been characterised by a single-minded search for knowledge and a solitary pursuit of perfection.

Hordes of spectators turned up at Cape Kennedy on 16 July 1969 to witness at first hand the launch of the enormous Saturn V rocket and the Apollo 11 crew. Four days later, Armstrong guided the lunar module Eagle past a large crater for a perfect touchdown on the Sea of Tranquility. “Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed,” Armstrong declared.

Six and a half hours later, a worldwide TV audience of 500 million watched as Armstrong’s ghostly figure slid down the ladder. His slow motion jump on to the pristine lunar surface culminated in the immortal words: “That’s one small step for man; one giant leap for mankind.”

As they left their footprints in the dust and learned to walk in one-sixth gravity, he and Buzz Aldrin were under instructions never to stray more than 45 metres from the lander. They had little time to stand and admire the view during their two-and-a-half-hour exploration of the moon’s surface. After setting up their experiments, collecting rock and soil samples, receiving congratulations from President Richard Nixon and deploying the American flag, it was time to return to the Eagle for a well-earned rest before returning home.

A little over 21 hours after the historic landing, the world held its breath once again as the crew prepared to make the first lift-off from another world. Eagle’s ascent stage did not let them down, and within a few hours they were reunited with Collins in the command module, Columbia. The three-day flight back home was something of an anticlimax. The crew did their best to entertain the watching millions on TV, but it was clear that they were better pilots and engineers than entertainers. One colleague called them “the quietest crew in manned spaceflight history”.

In the years that followed, each of the astronauts coped with their newfound fame in different ways. Armstrong was determined to act as a professional ambassador for the space programme at all times while resisting all attempts to pry into his personal life. After the excitement of Apollo 11, the most famous man in the world was given a desk job, as deputy associate administrator for aeronautics at Nasa headquarters in Washington DC.

Armstrong retained tenuous links with Nasa, turning out with his fellow crew members for Apollo 11 anniversary celebrations. He served on the National Commission on Space from 1985 to 1986, and was appointed as vice-chairman of the presidential commission that investigated the Challenger explosion in 1986. On 20 July 1989, he stood alongside George HW Bush as the president attempted – unavailingly – to inspire Nasa and the nation to undertake the manned exploration of Mars. Peter Bond

Jo Cox: Independent-minded MP who put her principles before traditional party politics

Died 16 June 2016

In a tragically short 15 months as an MP, Jo Cox made her mark as one of the brightest and best of the MPs elected for the first time at the 2015 general election. Many newcomers struggle to stand out from the Commons crowd, but the former head of humanitarian campaigning at Oxfam made an instant impact.

She called repeatedly for Britain to do more to help the victims of Syria’s civil war. She knew what she was talking about: she was still in regular contact with friends and former colleagues in the aid world working to help refugees in the region.

She set up a parliamentary group on Syria and staged Commons debates on the plight of the refugees. She argued forcefully that the UK government should be doing more both to help the victims and use its influence abroad to bring an end to the Syrian conflict.

Cox spent 10 years in the aid world, dangerous work which often took her to conflict zones. She worked closely with Sarah Brown, wife of then-prime minister Gordon Brown, as director of the Maternal Mortality Campaign to prevent mothers and babies dying needlessly in pregnancy and childbirth.

As an MP Cox described herself as “on the left of the party” and “definitely not a Blairite”, even though she backed Liz Kendall, the Blairite candidate, in the 2015 Labour leadership contest. She was seen as one of Jeremy Corbyn’s many critics inside the parliamentary Labour Party, but insisted she was a “critical friend” who wanted him to run an inclusive party with a message reaching beyond the traditional base.

She told The Independent: “Some of the people around him are very good at talking to the movement that helped propel Jeremy to power in the party – a really important constituency who are passionate, principled and excited ... They cannot be blind to the fact that that is not enough of a constituency or coalition to get us into power.”

An independent-minded spirit who did not want to be “put into a category”, Cox will be remembered for putting her principles before traditional party politics. In a very short space of time, she brought expertise and passion to the Commons which MPs and ministers will hopefully remember when they take decisions about Syria in future. Andrew Grice

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments