Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The interest rate on traded UK government debt has fallen to its lowest ever level, amid rising anxiety about the economic impact of the global Covid-19 outbreak.

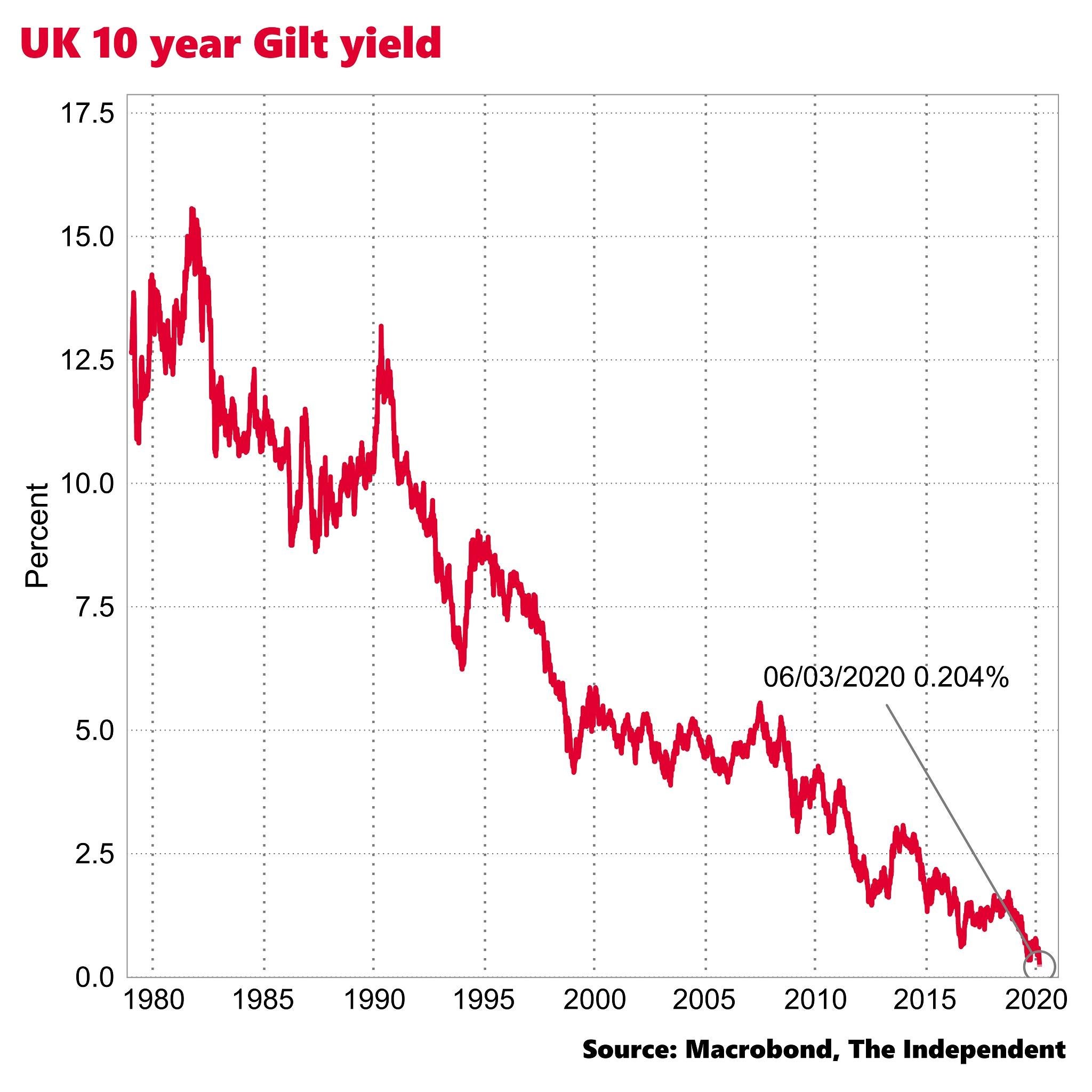

The yield (a name for the effective interest rate) on British government bonds which are due to be redeemed in a decade’s time fell to below 0.3 per cent on Friday afternoon.

But what’s driving Government borrowing rates in the financial market to such extreme low levels?

And is the market move itself something to be welcomed – or feared?

What’s happening to prices?

The price of UK government bonds is being pushed up, as traders and investors are increasingly keen to own them and are willing to pay more for the privilege of doing so.

This jump in bond prices automatically reduces the market yield on them (when the price of bond rises its interest rate automatically falls) hence the new record low yields we’re seeing.

This chart shows the yield on 10 year bonds over the past 40 years and how today’s rate sets a new record low.

Is it all due to coronavirus?

The recent dip is certainly driven by fears about the threat of a pandemic.

Traders expect the Bank of England to be forced to cut interest rates relatively soon to try to help support the UK economy in the face of this shock.

Reductions in the official short-term Bank interest rate tend to reduce traded UK government bond yields.

Also, with stock markets tanking, there’s generalised fear about holding riskier assets.

In times like this demand rises for the safest assets on the market place – which includes the UK’s debt. These, incidentally, are usually known as “Gilt-edged securities” or “Gilts” by traders, reflecting the view that they are as “good as gold”.

But the fall in the interest rate also reflects a growing pessimism about the UK’s growth prospects.

Rising Gilt yields in the UK (these days) have generally been a sign of market expectations that growth and inflation are going to pick up.

Falling yields signal the opposite – concerns that growth is going to be low, possibly even resulting in a recession.

But rates have been on a downward trend for much longer haven’t they?

Yes, as the chart shows they have been coming down over the past 40 years.

The reasons why are not fully understood.

Some think it’s a demographic and globalisation story – with high savings from certain ageing countries in Asia flooding into Western government debt and pushing down yields.

But others see it as a by-product of more fundamental problems related to the dynamism of Western economies, a kind of “secular stagnation”.

But isn’t it at least welcome that our Government can borrow so cheaply?

It certainly helps the Treasury financially to keep its interest bill down.

And this Government – unlike its predecessors since 2010 – has interpreted very low bond yields as an opportunity to borrow more to spend on transport infrastructure.

There is expected to be considerably more spending in this area announced in next week’s Budget.

Are low interest rates just a UK phenomenon?

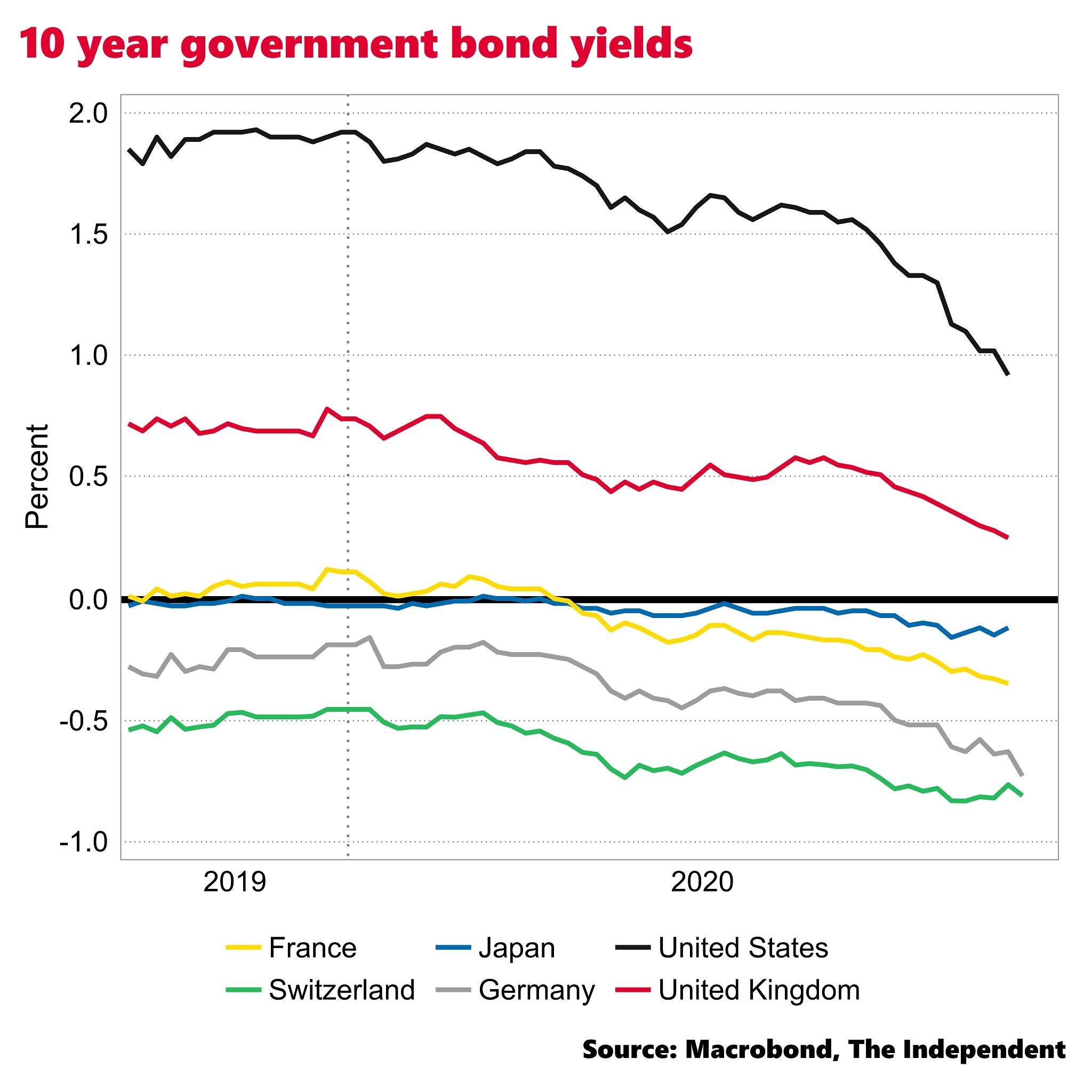

On the contrary, they are a common factor across the Western world, as this chart shows.

10 year government borrowing costs have hit record lows in America this week, with Treasury bonds dipping below 1 per cent for the first time ever.

Rates are negative in Germany, France, Switzerland and Japan, meaning investors are set to get less back over 10 years than the sum they initially invested.

Many have wondered in recent years how long this bizarre situation can last.

Thanks to the new shock of coronavirus hitting bond markets, it looks set to continue for a considerable time yet.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments