How cities could be designed to combat the loneliness epidemic

The cities we build in turn shape our society, says Tanzil Shafique. So when so many of us feel lonely, we should aim to apply what we know about the social impacts of design to help people connect with each other

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Do you feel lonely? If you do, you are not the only one. While you may think it’s a personal mental health issue, the collective social impact is an epidemic.

You may also underestimate the effects of loneliness. The health impact of chronic social isolation is as bad as smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

Loneliness is a global issue. Half-a-million Japanese people are suffering from social isolation. The UK recently appointed a minister for loneliness, the first in the world. In Australia, Victorian state MP Fiona Patten is calling for the same here. Federal MP Andrew Giles, in a recent speech, said: “I’m convinced we need to consider responding to loneliness as a responsibility of government.”

What do cities have to do with loneliness?

“The way we build and organise our cities can help or hinder social connection,” reads a report from the Grattan Institute, an Australian policy think tank.

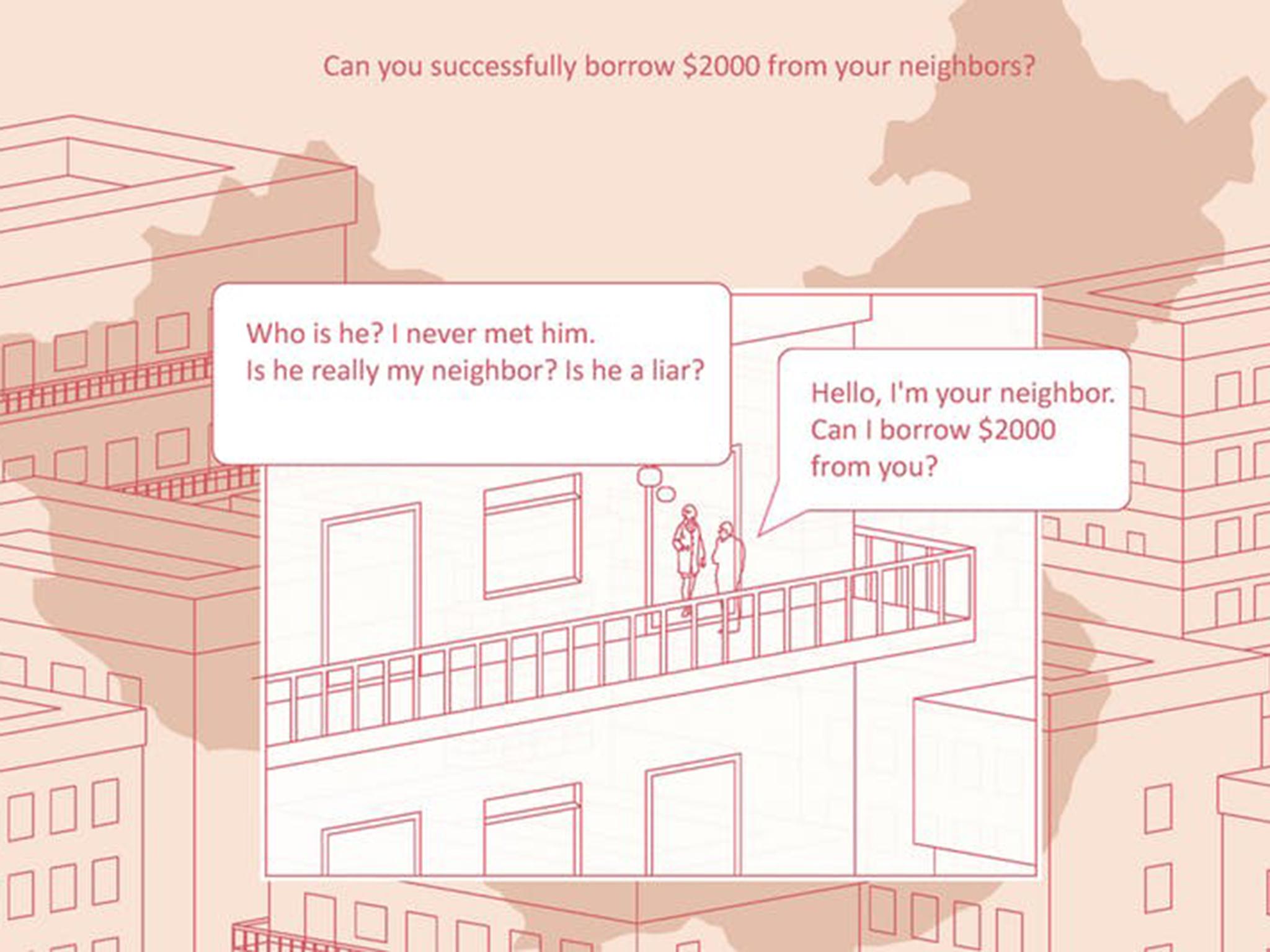

Think of the awkward silence in a lift full of passengers who never communicate. Now think of a playground where parents often begin chatting. It’s not that the built environment “causes” interaction, but it can certainly either enable or constrain potential interaction.

Winston Churchill once observed that we shape the buildings and then the buildings shape us. I have written elsewhere about how architects and planners, albeit unwittingly, are complicit in producing an urban landscape that contributes to an unhealthy mental landscape.

Can we think of different ways to be in the city, of a different architecture that can “cure” loneliness?

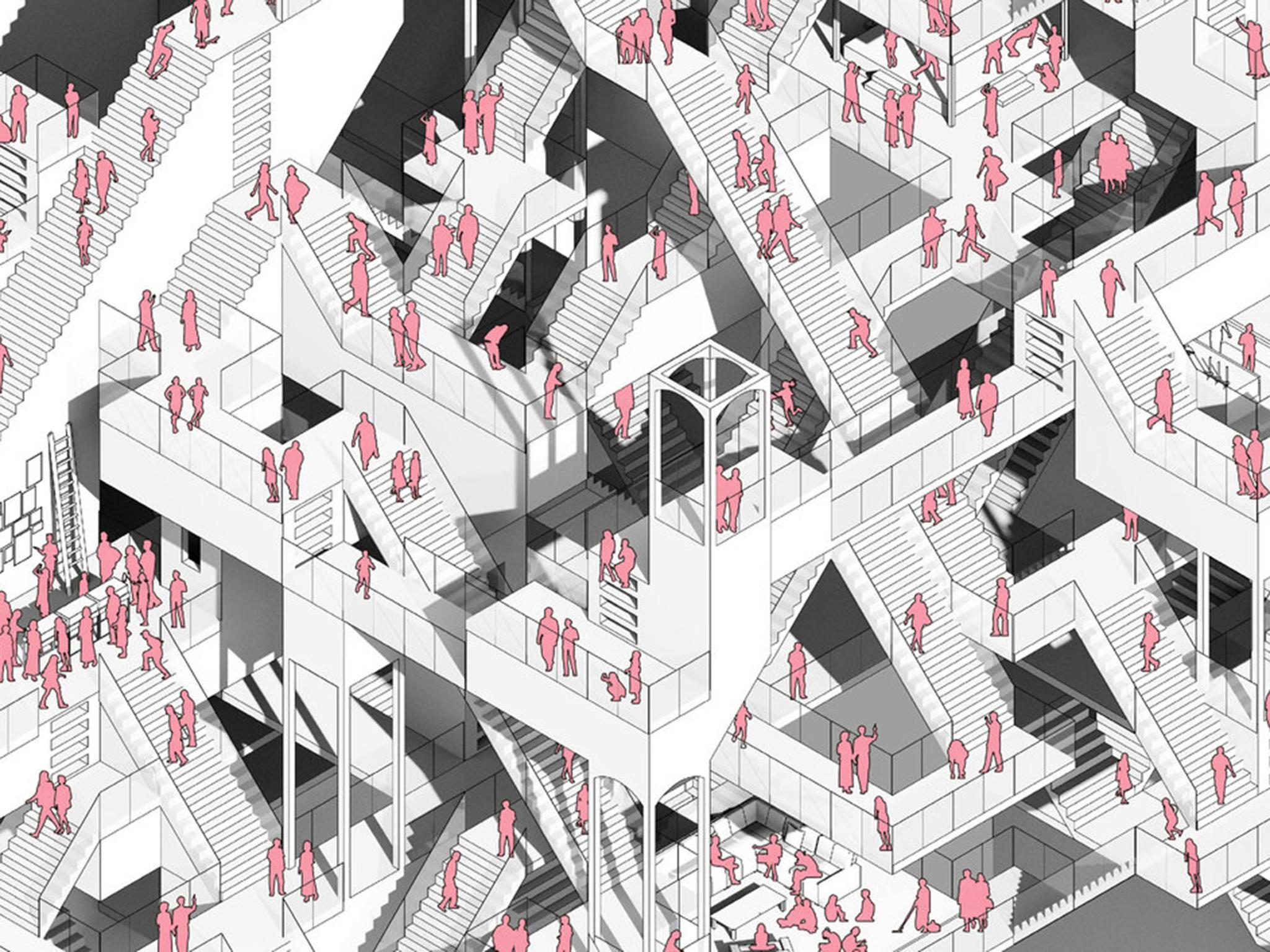

Taking this question as a point of departure, I recently conducted a graduate design studio at the Melbourne School of Design. The students, using design as a research methodology, came up with potential architectural and urban responses to loneliness.

Have you ever waited at a rail station, killing time without engaging with the person next to you? Diana Ong retrofitted the Ascot Vale rail station with multiple “social engagement paraphernalia” to promote conversations and activity. Michelle Curnow proposed to convert railway carriages into “sensory experience cabins” that attract people to explore the inbuilt gallery spaces and listen to other people’s stories while commuting. Who said commuting had to be boring?

Having a pet is one of the most effective ways to tackle loneliness, but often people don’t have enough time to care for one. Zi Ye came up with “Puppy Society”, an app that connects a pet with multiple owners. The dogs are housed in a shared facility where the owners come to pet the dog.

Denise Chan studied the Melbourne CBD laneways and found many of them are quite dead, despite being an icon of Melburnian liveliness. She reimagined the laneways revitalised with community plant gardens, book nooks and furniture to entice people to enter them and connect, say, during office lunch hours.

Are you one of those people who have a hard time eating alone? Fanhui Ding is, and she came up with a student-run restaurant for the University of Melbourne. Students get credit working on the aquaponic farms that supply the restaurant, which can be used to pay for a meal. People also get discounts for dining at the same table, encouraging students to interact over food. Given the many international students who suffer from loneliness, her concept used cooking, food and farming as therapeutic activity.

Beverley Wang looked at loneliness in the ageing population. She came up with a project called “Nurture”, for which she designed a kindergarten co-housed with a nursing home. Designing spaces for storytelling, she brought the elderly into the kindergarten as informal learning aides, giving them a sense of purpose.

There is an utterly different kind of loneliness that accompanies the loss of a loved one. Malak Moussaoui, taking note of this, designed an installation that grows flowers on itself to be inserted into cemeteries. Instead of just buying some flowers on the way, Malak’s design is meant to bring people together, introduce flower gardening as a therapeutic measure and give people spaces to mourn together. They might then meet other people who share similar stories of loss and connect.

Other students tackled more familiar cases, such as designing more social interaction spaces in highrise apartment buildings and redesigning supermarkets to make them places for people to visit on a Sunday morning. The student work can be viewed here.

Moving beyond merely analysing the problems, the research output shows that an alternative, less lonely future is indeed possible. Without claiming to solve loneliness, design can be a important tool in response to it.

Tanzil Shafique is a PhD researcher in urban design at the University of Melbourne. This article is republished from The Conversation (conversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments