Why it feels so good to read about Princeton professor Johannes Haushofer’s failures

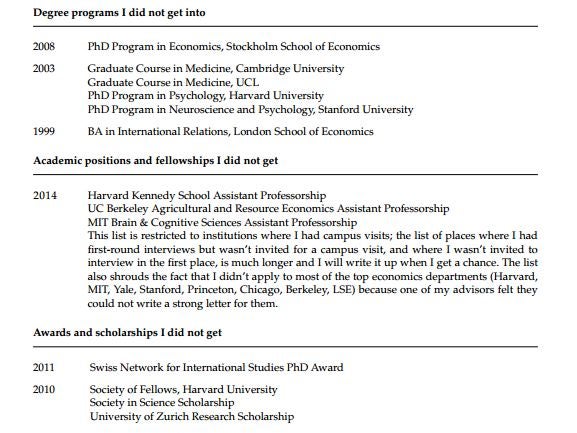

A recent “CV of failures" includes “Degree programs I did not get into” and “Research funding I did not get”

Most of us have had some momentary feelings of inferiority when looking over the résumé of a friend or job applicant. When you look at someone else’s shining educational and professional accomplishments, it’s easy to feel that the person in question is far more impressive than yourself.

But any accomplished résumé – or CV, as non-Americans and some in the professional class like to call them – hides secrets. If you could read between the lines of the many successes that are recorded in a résumé, you would probably see far more failures: schools people didn’t get into; scholarship essays that were toiled over and rejected; job applications that now seem harebrained.

In just showing the successes, a résumé or CV actually reflects only a tiny slice of one’s experience – and perhaps not even the most important part.

That’s the idea behind a recent “CV of failures,” published by Johannes Haushofer, a professor who teaches psychology and public affairs at Princeton. Haushofer’s CV of failures, which he published online for all to see, includes degree programs he didn’t get into, research funding he didn’t receive and paper rejections from academic journals.

“Most of what I try fails, but these failures are often invisible, while the successes are visible,” Haushofer writes. “I have noticed that this sometimes gives others the impression that most things work out for me. As a result, they are more likely to attribute their own failures to themselves, rather than the fact that the world is stochastic, applications are crapshoots, and selection committees and referees have bad days.”

Note his last meta-failure: "This darn CV of Failures has received way more attention than my entire body of academic work."

In an email, Haushofer said he first wrote out a CV of his failures in 2011, after a friend had a professional setback and he wanted to show support. The response was positive, so he thought it would be useful to make it public. "I'm hoping that it will be a source of perspective at times when things aren't going well, especially for students and my fellow young researchers," he wrote in an email.

Haushofer adds that if his CV of failures seems short, it’s probably because he’s forgetting some things. And a longer CV of failures could very well be a good thing – it might mean the person is good at trying new things.

The original idea for a CV of failures comes from an article published in the journal Nature in 2010 by Melanie Stefan of the University of Edinburgh, who argued that creating a visible record of failures is a powerful way to help other people deal with their own shortcomings. Whereas we’re intimately familiar with both our professional successes and our failures, other people just see a string of accomplishments -- and that can be discouraging.

“As scientists, we construct a narrative of success that renders our setbacks invisible both to ourselves and to others,” Stefan writes. “Often, other scientists’ careers seem to be a constant, streamlined series of triumphs. Therefore, whenever we experience an individual failure, we feel alone and dejected.”

She advises people to keep a CV of failures, to remind themselves that failure is an essential part of what it means to be a scientist, and perhaps to inspire a disheartened colleague along the way.

Stefan points out that academic fellowships have a success rate of only about 15 percent – meaning that for every hour spent writing a successful fellowship application, she probably spent six toiling for naught.

Of course, this kind of ratio is true in other fields as well. Many famous business people, including Henry Ford and W.H. Macy, went broke repeatedly before hitting it big. And it seems as though almost every famous writer or musician was rejected dozens of times before achieving success.

Copyright Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments