UK ‘lukewarm and evasive’ over G7 plan to curb tax avoidance by multinationals

Other countries all back plan to end abuse of the global system that costs governments hundreds of billions of dollars each year

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Boris Johnson’s government been “lukewarm and evasive” over a multilateral agreement that could drastically curtail tax dodging by large corporations, campaigners say.

The UK is the only G7 nation not to have backed a global minimum corporate tax rate that would reduce incentives for multinationals, including tech firms such as Google, Apple and Amazon, to shift profits into tax havens.

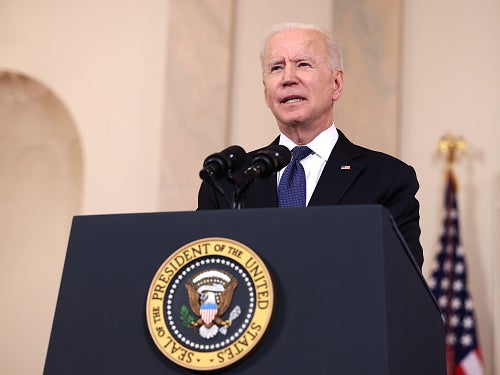

Momentum is gathering for reform after US president Joe Biden backed a 15 per cent rate that could reap billions of dollars a year for governments.

The level is lower than the 21 per cent that had been mooted, but the UK has yet to issue its support. Conservative MPs on Monday voted against an amendment tabled by Labour that would have given the UK’s backing to the plan.

The prime minister’s spokesperson would say only that the government welcomed the US’s “renewed commitment to reaching a solution”.

He added: “It's crucial that any agreement ensures digital businesses pay tax in the UK that reflects their economic activities.”

In Parliament on Monday, Jesse Norman, financial secretary to the Treasury, said the government supported the proposals being negotiated by the OECD, which include a minimum tax rate and measures to discourage profit-shifting into low-tax jurisdictions.

Almost 140 countries hope to reach a deal on tax avoidance by this summer.

The Financial Times reported on Monday that the G7 could seal a pact as early as Friday that would spur action on the global standard.

G7 countries that back Biden's corporation tax proposals

— Anneliese Dodds 💙 (@AnnelieseDodds) May 24, 2021

🇩🇪 Germany

🇨🇦 Canada

🇫🇷 France

🇯🇵 Japan

🇮🇹 Italy

🇺🇸 USA

G7 countries that don't

🇬🇧 UK

The Conservatives have a choice: back British businesses paying their fair share, or let tax-avoiding tech giants off the hook again.

Paul Monaghan, director of Fair Tax Mark, a scheme that certifies organisations that pay “the right amount” of tax, said an agreement on the proposals would be a “tremendous moment” for tax justice.

“This would see many of the incentives underpinning profit-shifting to tax havens removed, and would see the very largest multinationals taxed not just on where subsidiary profits are booked, but where real economic value is derived,” he said.

“To date, the UK government has been lukewarm at best, and has seemed intent on steering discussions to more minor areas, such as an enhanced digital services tax.

“We could be on the cusp of a once-in-a-generation moment, but the UK needs to step up and engage with the agenda much more positively – the benefit to public services here and in the developing world could be immense.”

What are the proposals?

Joe Biden and vice-president Kamala Harris originally put forward a plan for a minimum tax rate on company profits of 21 per cent. For comparison, the UK’s rate is currently 19 per cent after years of reductions. The average among the OECD club of wealthy nations is 20.6 per cent.

The Biden administration also signalled its commitment to ensuring profits are taxed where they are actually made, rather than where a company’s accountants decide to book them.

This would put an end to cases such as Apple selling most of its iPhones from Ireland (on paper) where it pays a rate on profits of less than 1 per cent. Other “tax planning” techniques include sending a bill for “intellectual property” from a subsidiary in a tax haven to one in a higher-tax country.

This allows multinationals to handily shift profits out of countries with governments that want to take a slice of profits to pay for the public services on which companies rely.

What benefit might they have?

The earlier proposal for a 21 per cent tax rate would have brought in a staggering $640bn a year globally, according to the UK-based Tax Justice Network (TJN). While the 15 per cent rate would obviously yield less, it would put an end to some of the most egregious examples of profit-shifting and, it is hoped, end the race to the bottom on tax.

TJN is calling for a mechanism to ensure that poorer nations receive a fair share of the benefit from a global agreement.

Developing countries are hit hardest by the effects of tax avoidance, while wealthier nations, including the UK, are the main facilitators.

Could raising taxes hurt business?

It’s hard to argue that a 15 per cent rate – still lower than most countries in the world – would be harmful.

Business groups have for years lobbied for lower tax rates and have largely got their wish. Taxes on company profits have been falling for decades, in part due to an erroneous theory that lower rates mean a higher actual tax take for governments. The UK government pushed this line until it recently admitted that a higher rate increased revenues.

Tax rates have in part been reduced because of “tax competition”, otherwise known as a race to the bottom, which has been spurred by countries including Ireland, the Netherlands and the UK’s network of overseas territories.

While this has long been a contentious issue, the surge in public spending has added to scrutiny on tax havens as government ministers look for ways to bring in additional revenue.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments