UK economy grinds to a halt

After 16 years, longest period of growth ends

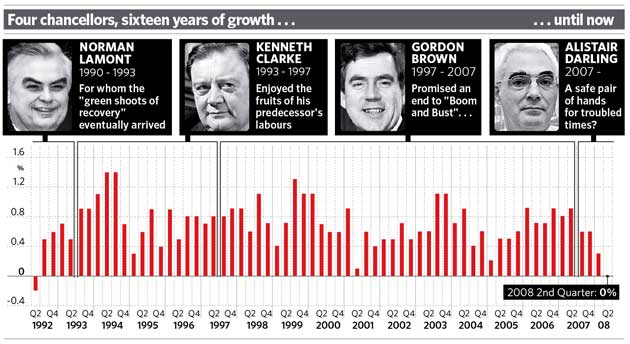

The boom is officially over. Growth in the economy ground to a halt in the second quarter of this year, thus ending the longest period of expansion in British economic history. The bust may not be far behind: many economists now believe an outright recession – two successive quarters where the economy shrinks in size – will follow later this year, a period of contraction that could extend well into 2009.

A generation too young to remember the last severe downturn will soon have to face such unfamiliar phenomena as rising unemployment, negative equity, home repossessions, large-scale bankruptcies and stagflation, as inflation continues to climb even as the economy stagnates.

At 5 per cent per annum, as measured by the RPI, inflation was last this high in July 1991, on its way down, while growth was last lower in the second quarter of 1992, when Britain was climbing out of the last recession. The "difficult and painful" year that the Governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, predicted last week seems to have arrived.

The Office for National Statistics yesterday revised its estimates for growth for the second quarter of this year downwards, from an increase of 0.2 per cent to zero, thus ending the run of 63 successive quarters of expansion.

Technically, the statistics revealed that the UK economy actually did grow between April and June, with the total value of goods and services produced in the UK rising from £315.510bn to £315.629bn, a rise of £119m, or 0.04 per cent – a minuscule increase by recent standards.

Household spending fell by 0.1 per cent, but construction, financial services and investment generally is being hard hit, with only a relatively strong performance from exports and a fall in imports preventing a slip into negative growth. Removing the trade figures puts the purely domestic economy in decline for the past two quarters and thus in recession, as one member of the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee, David Blanchflower, has already declared. All the indications are that things will get worse before they get better, and on a historic scale. Consumer confidence is running at levels not seen since 1974, with sentiment in the housing market registering 30-year lows; forward business orders are also hitting near-record poor performances.

There are signs the credit crunch is easing but first-time buyers are still finding it almost impossible to find a mortgage – and fewer want one as house prices fall by 10 per cent a year. Meanwhile, gas price rises are set to push inflation above 5 per cent, slowing the economy further.

There is a belief in the City that recession will force the Bank to cut rates by the end of the year. It has predicted "broadly flat" growth this year, and conceded a likelihood of two or more quarters of negative growth. Yesterday, the pound fell on expectations that rates would be cut sooner. Sterling hit its lowest level for a week against the euro.

However former Conservative chancellor Kenneth Clarke said he did not think the Bank would cut interest rates. "My feeling is that they will have to be raised because inflation is going to be a problem. The Bank cannot do anything about oil prices and it cannot do anything about global food prices," he said. "But it's got to make sure we don't get into a wage-price cycle bringing back really high inflation and making any slowdown worse than it otherwise would be."

Mr Clarke said a Tory government might inherit a "real mess" and will face "tough choices".

Vicky Redwood, UK economist at Capital Economics, said: "There must be a strong chance, now that output is falling, that the UK has already entered a technical recession."

Figures this week suggested the slowdown had resulted in a £2.2bn shortfall in stamp duty revenues already this year, and government spending rising faster than ministers assumed.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates that a 1 per cent drop in growth adds about £2.5bn to public borrowing. Given that the Budget in March was based on a projection for growth this fiscal year of 2.5 per cent, Alistair Darling will face a black hole of at least £12.5bn in the public finances.

Crowing about growth

9 March 1999

Gordon Brown: "I can confirm our growth estimate for 1999 of 1 per cent to 1.5 per cent, which is what I told the House in November, followed by stronger growth."

21 March 2000

GB: "Today, I can report that in 1999, instead of the recession that many forecast, the British economy grew by 2 per cent. And Britain has been growing steadily while meeting our inflation target."

16 March 2005

GB: "Britain is today experiencing the longest period of sustained economic growth since records began in the year 1701."

21 March 2007

GB: "I can report... that after 10 years of sustained growth, Britain's growth will continue into its 59th quarter – the forecast end of the cycle –and beyond."

12 March 2008

Alistair Darling: "While other countries have suffered recessions, the British economy has now been growing continuously for over a decade – the longest period of sustained growth in our history."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies