Reversing monetary stimulus need not impact the UK economy, says Bank of England interest rate setter

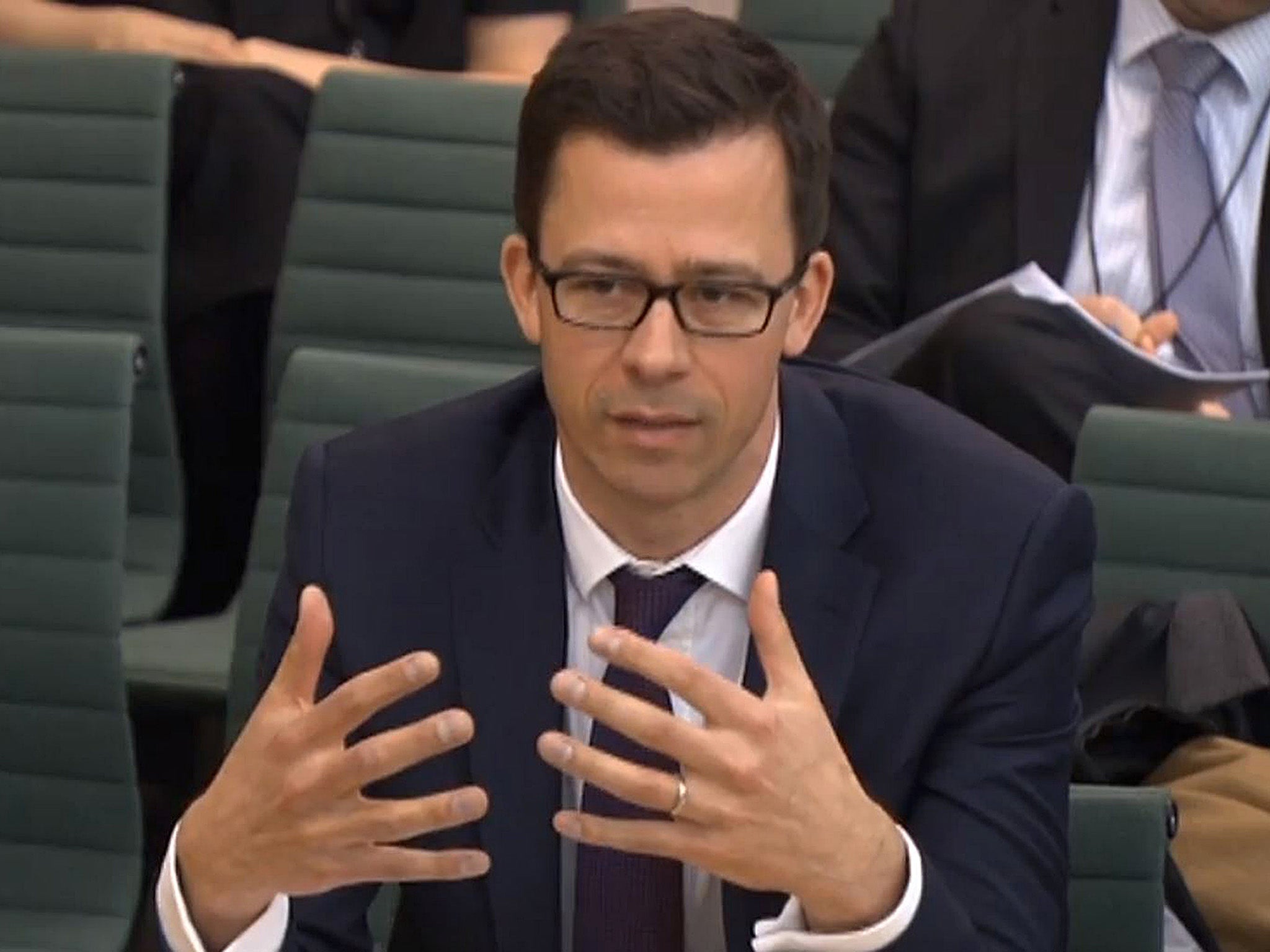

'Unwinding QE need not have a material impact on the shape of the yield curve, or indeed on the economy, if properly communicated and done gradually,' said Gertjan Vlieghe of the Monetary Policy Committee

When the Bank of England starts to sell off its £435bn stock of government bonds acquired under its Quantitative Easing programme there could be little material reaction in the UK economy, a member of the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee has predicted.

The general assumption among policymakers and financiers has been that the winding down of monetary stimulus would have a similar impact on the economy to asset purchases but in reverse, meaning a dampening of overall activity and a shift in the UK borrowing yield curve.

The Bank of England has also previously argued that QE helps the economy through a "portfolio rebalancing" channel, by encouraging asset managers to buy riskier assets than government bonds, which lowers the cost of capital for private firms and encourages investment.

But Gertjan Vlieghe, an external member of the MPC, argued against this conventional wisdom in a speech at Imperial College Business School in London on Tuesday.

“My view that QE works primarily via expectations, with additional powerful liquidity effects that are temporary and mainly relevant during periods of market stress, implies that unwinding QE need not have a material impact on the shape of the yield curve, or indeed on the economy, if properly communicated and done gradually,” he said.

The bank said in June that it will not consider reducing its stock of government bonds until the bank rate is 1.5 per cent, double its current 0.75 per cent rate.

Financial markets are not currently pricing this in to happen until after 2021.

When this happens, Mr Vlieghe said, “expectations of future policy rates can once again be influenced by changing current policy rates and continuing communication, exactly as was the case in pre-QE days.”

“Provided this is well understood by households, businesses and financial markets the unwind of QE should then have no additional effect on expectations, and therefore on the economy”.

The UK yield curve has flattened in recent months, meaning the interest rate on short-term borrowing has risen but the rate on longer-term debt has not risen commensurately.

Some have suggested that QE is responsible for artificially holding down long-term rates. But Mr Vlieghe said the explanation was rather a reversion to a long-term historical norm.

“Since Bank of England independence [in 1997] the fundamentals of inflation and inflation risk have become more similar to the gold standard era than to the 20th century average, and in particular are very different from the 1970s and 1980s. So we should expect yield curves to be flat again, on average,” he said.

“Does QE not affect the yield curve? Of course it does. But it does so primarily by affecting expectations of future monetary policy, revealing the central bank’s reaction function. This anchors inflation expectations even when interest rates are constrained at the effective lower bound, which in turn affects a wide range of asset prices, economic growth and inflation.”

The Bank of England began its QE programme in 2009 during the financial crisis. It was able to cut its main policy rate no further and so resorted to buying government bonds in order to support the overall economy.

Over the past nine years it has acquired a stock of £435bn of “Gilts” or UK sovereign bonds.

In the US, the Federal Reserve acquired more than $4.5 trillion of assets as part of its own stimulus programme. It began winding down its holdings in October 2017, with no obvious adverse affects on the UK economy thus far.

Asked about the risk of a no-deal Brexit, Mr Vlieghe said: “We’re not keen to be making a running commentary on what becomes slightly less likely or slightly more likely”.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies