The charts that show why China really is responsible for the plight of the UK steel industry

The Chinese ambassador's attempt to exonerate China from the charge of global steel dumping is not convincing.

“It is regrettable that some people in Britain blame China for what is happening in the British steel industry and accuse China of 'dumping' steels in Britain and pricing local companies out of the steel market”

So says that Chinese ambassador to the UK, Liu Xiaoming, in a defensive article for today's The Daily Telegraph.

No doubt it’s regrettable from his perspective that people in the UK are complaining of Chinese dumping. It's an uncomfortable thing to be accused of. But that doesn’t make the dumping charge untrue.

Here’s why, in 10 charts and tables, we should be sceptical of Mr Liu's case.

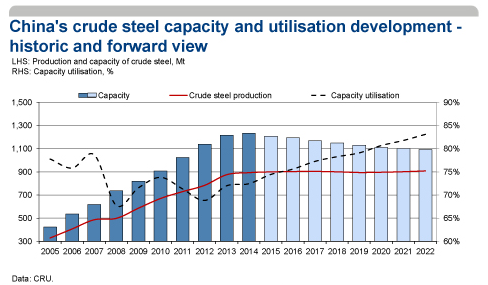

There is huge overcapacity in the domestic Chinese steel industry.

Less than 75 per cent of its domestic capacity is being used according to data from the analysis firm Cru:

It’s important to recognise that this overcapacity has been created by an avalanche of cheap loans from state-owned banks to state-owned steel companies. The Chinese corporate sector is notoriously over-leveraged. And Chinese steel companies are among the most over-leveraged of all companies in China as this (showing interest payments as a percentage of operating profits) demonstrates:

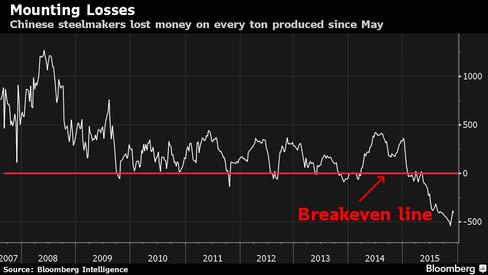

If you think Tata's Port Talbot plant has problems with losing money take a look at the negative profitability of Chinese steel makers:

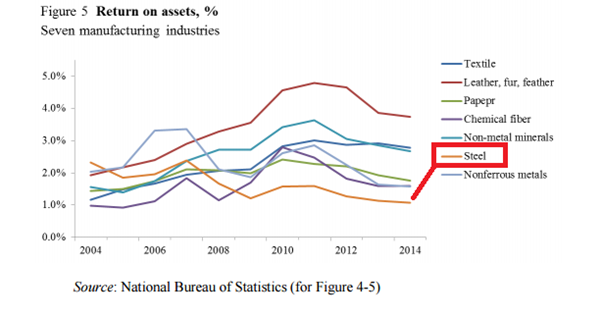

Overall profit margins in Chinese steel manufacturing were already pitifully low relative to other sectors of the Chinese manufacturing economy. And they have been falling further:

Two factors have driven that lavishing of China's national resources on steel production in recent years. One is cronyism and corruption. The other has been a political concern in Beijing to keep manufacturing employment levels high. That concern is entirely understandable. But these activities have global economic implications that must be recognised.

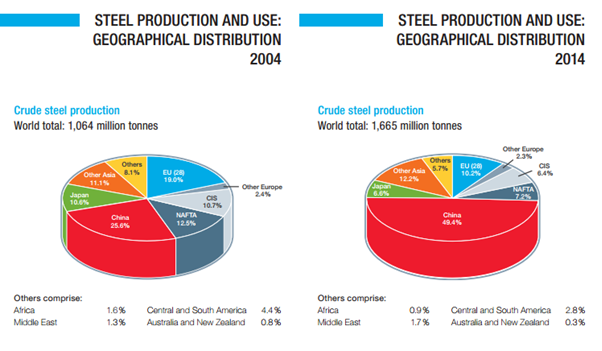

China is easily the world’s biggest producer of steel. China’s share of output has risen from a quarter to a half in a decade:

There is global overcapacity in steel, but China is easily the biggest source of it:

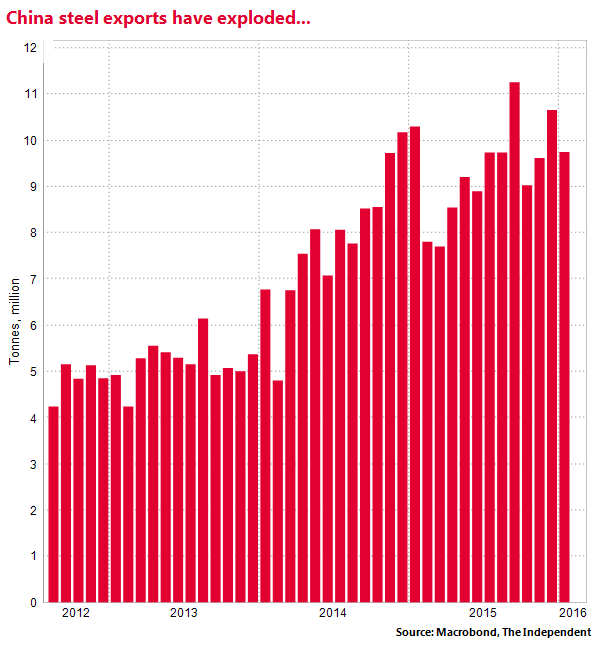

If that capacity merely had domestic impacts in China that would be one thing. But its monthly exports have exploded:

China almost exports more in a month now than the UK industry produces in an entire year.

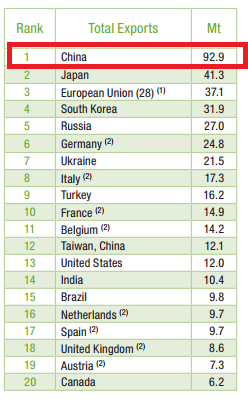

The country is now easily the world’s biggest exporter of steel by volume as this from the World Steel Association (in millions of tonnes produced a year) shows:

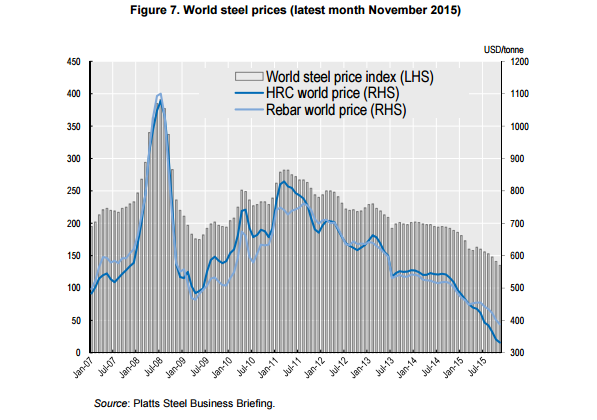

And that surge in exports is one of the central reasons the global steel price has collapsed:

The big losses of Chinese steel firms is strong evidence that China's steel is being sold in international markets at below its true cost of production.

And China readily admits that it has overcapacity, having laid out plans to reduce annual capacity by 100-150 million tonnes and to reduce employment in the sector by 500,000 workers.

But political and economic dysfunction in Beijing means that success cannot be assumed.

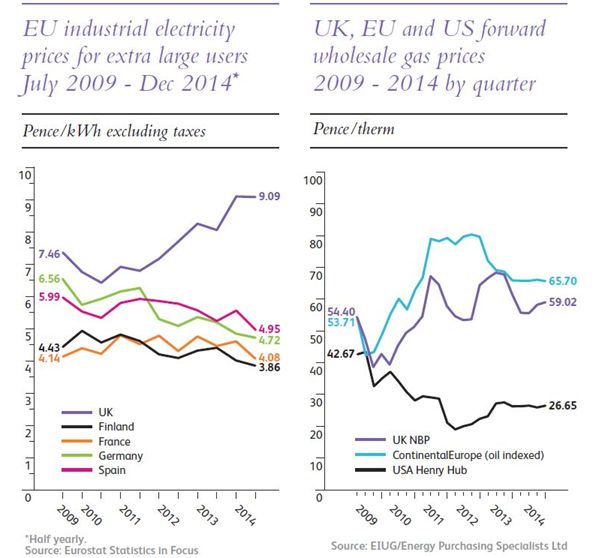

The difficulties of the UK steel sector are not entirely due to China. There is a legacy of underinvestment. An excessively strong sterling over the past thirty years has not helped the sector's international competitiveness. UK firms have high energy costs relative to other nations in Europe, as this from the EEF manufacturers' organisation shows:

Yet Mr Liu is wrong in his main point. China is a major big part of the story of the current plight of the UK steel sector.

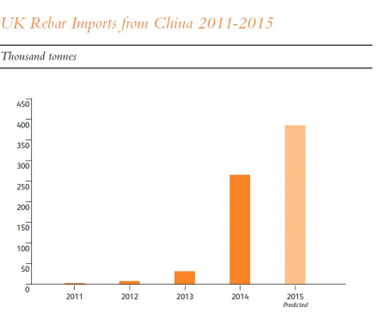

The ambassador says Chinese exports are only 11 per cent of UK steel imports. But that’s a sharp rise on previous years as this. also from the EEF, shows:

Moreover, it’s China’s influence on the global price of steel that matters, not its share of UK imports. A glut of Chinese steel supply in Europe will force down the European price and prompt more cheap imports to the UK from mainland Europe. The volume of direct UK imports from China is less important.

Tough European-level anti-steel dumping tariffs on China are probably warranted under the World Trade Organisation rules (as the American government has already decided) since it's pretty clear that China is producing steel with heavy government subsidies (in the form of cheap loans and state-owned bank forbearance of loss-making firms) and selling the product on world markets below its true cost.

The UK government's decision should not be based on abstract musing over the principle of protectionism versus openness but a cost-benefit analysis. Are the benefits of shielding UK steel industry from cheap Chinese imports likely to outweigh the costs of higher-than-otherwise steel import costs for successful UK manufacturers such as car makers?

Another factor that should shape the UK policy response is the likelihood of a medium-term steel price recovery. Could tariffs help buy time for a credible buyer for Port Talbot to emerge and to save what's left of British steel production? Or by seeking protection would ministers be in danger of distorting the domestic economy in other, perhaps less visible. ways?

These questions are certainly open to debate. The question of whether China is dumping steel or not, should not be.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments