The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

How to disagree with people from 20 different countries

Remember when Michelle Obama hugged the Queen?

As a bumbling American abroad, there is no end to the ways that you can offend people and embarrass yourself in the process.

President Carter succeeded in 1977, when he told the Polish people, through an unfortunate translation, that he desired them “carnally.” President Bush offended Australians in 1992, when he gave a “V-for-victory” sign, the equivalent to a middle finger down under. And Michelle Obama had her own moment when she half-hugged the Queen in 2009, perhaps the only incidence of public hugging in the Queen’s 57-year career.

Erin Meyer, a professor at the global business school INSEAD, has accumulated her own thoughts on how to navigate cross-cultural missteps in a new book, “The Culture Map.”

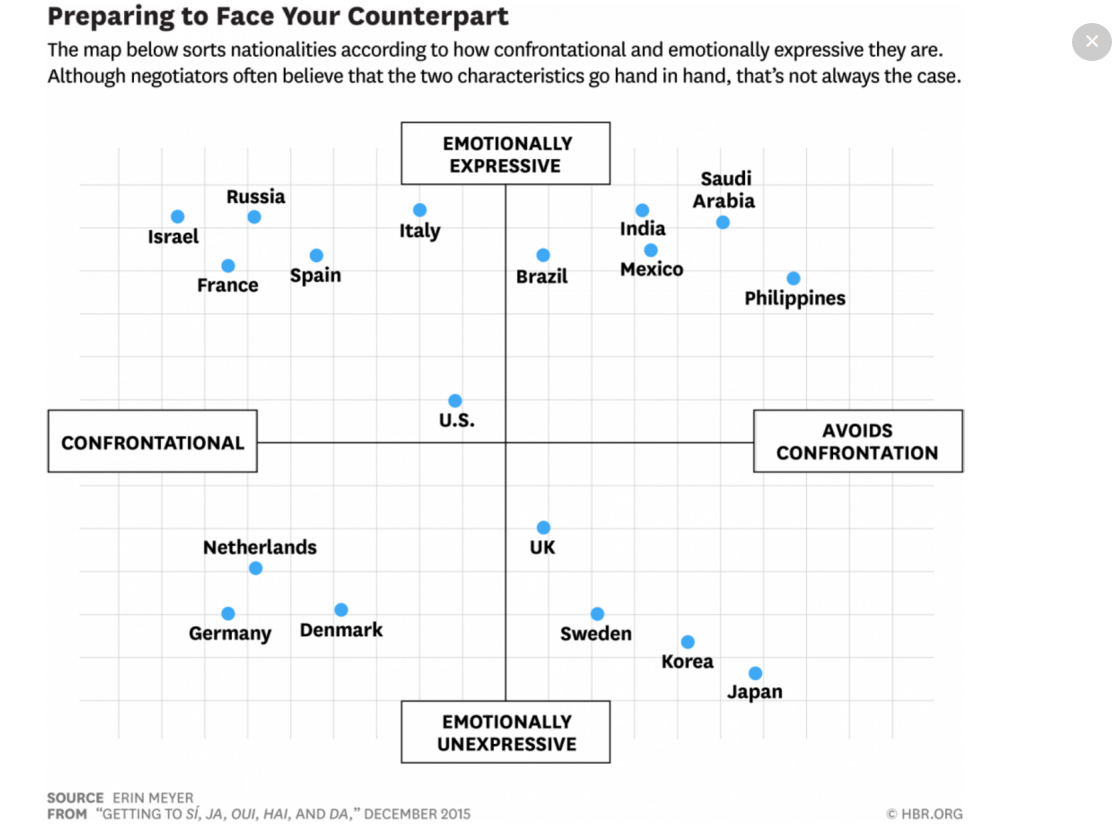

One chart that appears in the book, reprinted here with her permission, is particularly great at decoding some of the perils in cross-cultural communication.

The chart is based on Meyer's own surveys and experience of working cross-culturally. Of course, reducing something as amorphous as culture into one dot on a graph is both difficult and subjective. But her graphs do reveal something interesting about how to successfully navigate cultural differences.

The chart combines two different scales. The first scale looks at how emotionally expressive people in that culture tend to be – whether they raise their voices, touch each other, or laugh passionately when talking, or whether this kind of emotionally expressive behavior is considered unprofessional.

As the chart below shows, Meyer places stoic Scandinavians and deferential East Asians at one end of the scale. At the opposite extreme are those cultures where people express their emotions openly and sometimes gesture enthusiastically when speaking – India, Italy and Spain.

On top of this, Meyer adds another scale, which measures how confrontational people in a culture tend to be, to create the 2-D chart below.

People often mix up emotional expression with confrontation, but they are not the same thing, Meyer says -- in some cultures, people tend to be passionate in their speech and expression but don't criticize other people openly, while other cultures embrace the opposite.

The upper-left and lower-right quadrants of the graph are probably the easiest to understand, says Meyer.

Cultures in the upper left, like Israel, France and Russia, are direct and easy to read. They tend to express their emotions passionately and their disagreements openly. They typically see disagreement and debate as a positive thing that won’t hurt a relationship, Meyer says.

The cultures in the lower-right quadrant are much the opposite, those where emotions and disagreements tend to be expressed more subtly. Countries including Japan, Korea and Sweden are known for being rather emotionally unexpressive. They also studiously avoid open disparagement and take criticism personally, viewing the critique of an idea as a critique of the person who introduced it.

The other quadrants are a little more complicated. Countries like the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark, in the lower-left quadrant, are not very emotionally expressive, says Meyer. Yet they tend to express disagreement bluntly and openly and believe in the value of open debate to generate truth. They are not trying to be disrespectful, but rather honest and transparent.

Finally, there are the countries in upper-right quadrant, including India, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, Mexico, Peru and the Philippines. These countries are emotionally expressive but also avoid confrontation – a combination that can be very confusing to outsiders. People in those cultures seem very open, but they tend to be sensitive to criticism.

Learning to work around these differences can be difficult, says Meyer. She cautions that people working across cultures need to make an effort to learn when to express their disagreement and when to soften it or bottle it up.

In her book, she quotes a German finance director at KPMG, Markus Klopfer, as he describes how he has learned to temper his criticisms for his British colleagues:

“I try to start by sprinkling the ground with a few light positive comments and words of appreciation,” Klopfer says. “Then I ease into the feedback with ‘a few small suggestions.’ As I’m giving the feedback, I add words like ‘minor’ or ‘possibly.’ Then I wrap up by stating ‘This is just my opinion, for whatever it is worth,’ and ‘You can take it or leave it.’ ”

Copyright Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments