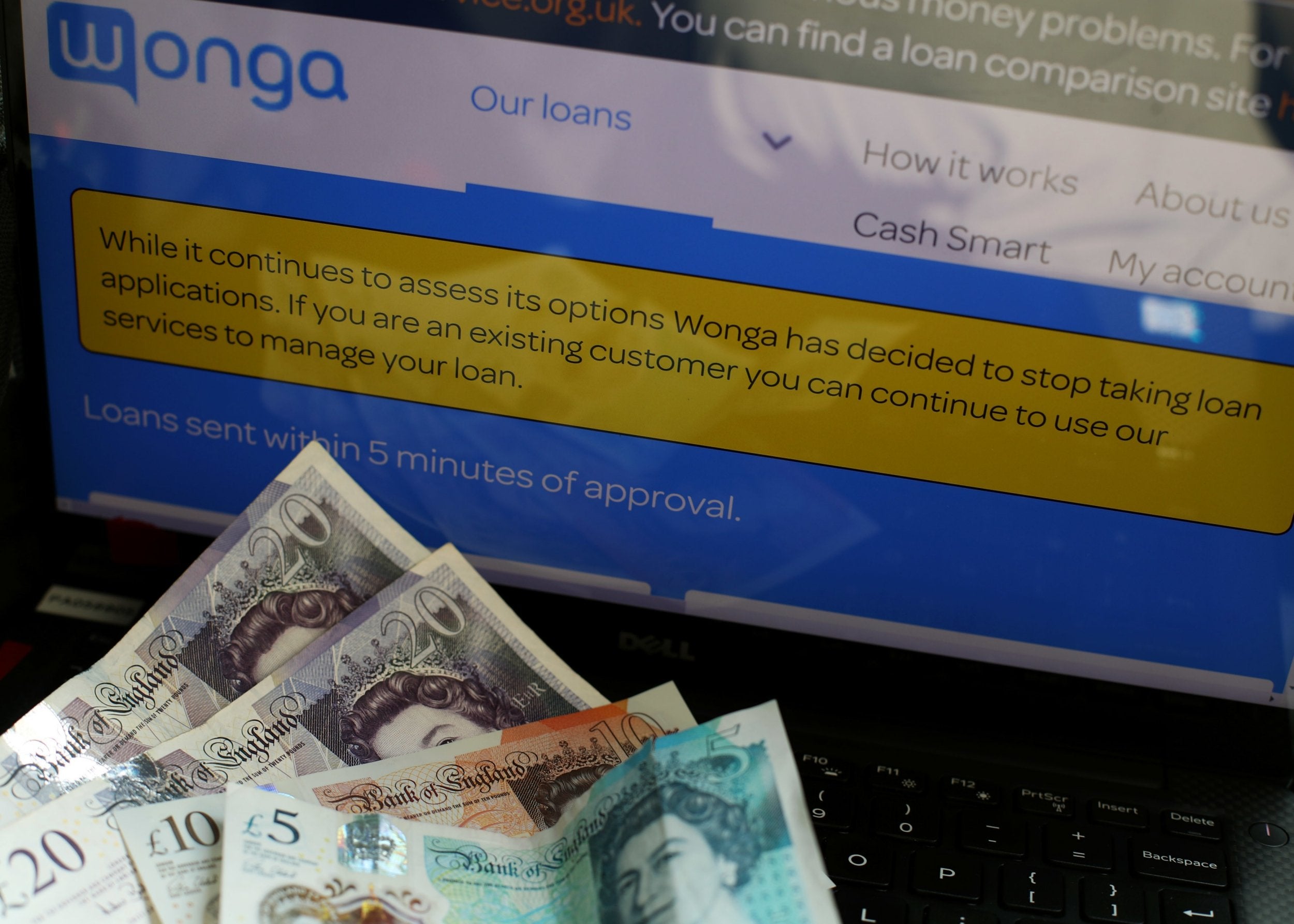

Wonga’s demise shows us technology is not always the answer

Wonga ensured it became nationally-known, but it was then only a short step to becoming a by-word for exploitation and grasping behaviour

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Time for a confession. I was once a fan of Wonga.

It was not when I met Errol Damelin, the short-term money lender’s softly-spoken, persuasive founder. Damelin had a nice line, about how, as an ex-investment banker with a penchant for technology, he’d sold his software business and was casting around for an industry that was “crying out for change, one where the incumbents had no incentive to change because to do so would upset their business models”. He alighted on internet money lending. Damelin started Wonga in 2006, and within four years, just as I met him, it had made its one-and-a-half millionth loan.

No, it was not Damelin. It was because my eldest son, then in his mid-twenties, was one of its users. Where once he would turn to the bank of his parents to tie him over until he next got paid, now he went to Wonga. If he was heading into a heavy social weekend, he would borrow £100 or so from Wonga, and repay the money the following week.

It was neat and simple, and avoided the angst of him pleading with me to sub him yet again. I recall telling this to Damelin, and the Wonga boss voicing his approval – that was exactly the gap in the market that his firm wished to plug. My son applied online, quick and simple, he got his cash, he paid it back with a bit of interest – and both parties were happy.

Except that isn’t what happened. Now, Wonga has hit rock bottom, having suffered successive years of heavy losses and written off customer loans worth hundreds of millions of pounds.

Damelin has long gone – he cashed in part of his shares and quit as chief executive five years ago. His fellow shareholders now face losing their entire investment.

Wonga’s collapse is as spectacular as its rise. My interview with Damelin was headlined: “Doing for Money-Lending What Amazon Did for Books”. How embarrassingly wrong I was. But in my defence, I was not alone. Wonga really was being spoken of as being a British equivalent of Facebook, Twitter, Google and Amazon. Its backers were true industry heavyweights who knew a thing or two about game-changing tech businesses. Damelin said, truthfully, Wonga was “growing at a scale that makes us one of the five fastest-growing start-ups of all time.” There was talk of seeking a $1bn (£769m) valuation on the New York stock market, even though its profits were less than £20m.

Where Wonga went wrong was that it became a target for campaigners against loan sharks. Yes, it’s true that its APR or annual percentage rate of interest on occasion exceeded 4,000 per cent. When Blackpool made it to the Premiership, a newspaper ran the headline: "2,689 reasons why Blackpool love affair is tainted already". That was a reference to the football club's shirt sponsor, Wonga, and its then APR of 2,689 per cent.

But that rate was never paid by my son. Damelin said to me at the time if you were to borrow £130 for 13 days, “Wonga will charge £22.87 in interest and fees. If the customer pays back early, they're only charged for the days they borrowed the money. About a quarter of our clients every month do that -– they might borrow for 13 and pay us after five.”

The problem was that while Wonga has clients like my son, who was employed and could pay back, it began to attract plenty who were not like him, who used Wonga as a way of supplementing their benefits. They could not repay, and that’s when the heavy penalties kicked in. Damelin had reckoned without human behaviour, that while he might have been interested in one segment of the market, another, far less attractive, rushed in – and without rigorous filters was also served by his company.

And with that, came the opprobrium of politicians and others. In truth, a lot of the time, they were protesting against the heavy men who patrol sink estates, the debt collectors who issue all sort of threats, and are prepared to follow them through with violence if the funds are not forthcoming. The problem was that while these characters remain in the shadows, using fear to guarantee silence, and stay largely hidden and unknown, Wonga was a bold innovator, promoting itself heavily, via sponsorship and advertising campaigns.

Justifiably proud of its technology and speed of service, Wonga ensured it became nationally-known. From there to becoming a by-word for exploitation and grasping behaviour was only a short step – but one that Damelin and his colleagues failed to appreciate.

Instead of tightening up their procedures, to showing themselves to be more discerning and interested in purely the likes of my son – “the Facebook generation” said Damelin proudly – they chose to fight their opponents and tackle them head-on. It was a disastrous strategy. MPs were able to drop the Wonga name, often under the protection of Parliamentary privilege. They were concerned, rightly, about the activities of money-lenders, but the one they cited, and the one that drew more attention to itself with forceful, vocal denials, was Wonga.

The brand appeared to symbolise much that was bad about modern Britain: slick financial types using their cleverness and state of the art equipment to rip-off ordinary people who had no control over their own spending, who were only too willing to borrow beyond their means.

When the authorities stepped in, and decided to act, the one name in their sights, the one the media could latch onto, was the most high-profile: Wonga. They introduced an APR cap of 0.8 per cent a day, and simultaneously, lawyers and claims management companies, went after the firm with a reputation to defend and the ability to pay. Claims against Wonga soared, and with the rise, came more bad publicity and yet more vitriol.

Wonga could no longer do any right. A slow, painful death ensued.

It’s a salutary tale. Technology, smart as it is, is not the full answer.

Chris Blackhurst is a former editor of The Independent, and director of C|T|F Partners, the campaigns and strategic communications advisory firm.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments