Don’t believe what you’ve read: the plummeting pound sterling is good news for Britain

A former International Monetary Fund official argues that the sharp decline in the value of the UK currency will help the British economy to rebalance and grow sustainably

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Brexit vote triggered a sharp outflow of speculative funds invested in the property sector – and that outflow caused the highly overvalued British pound to depreciate.

Thus, unanticipated by anyone, Brexit caused the finance-property bubble to deflate and, at the same time, steered the British economy towards more productive enterprise. Contrary to the dominant narrative, the pound’s depreciation carries a cheery message.

In the dominant narrative, the pound’s depreciation is the prime warning message that Brexit will end badly.

It signals, some say, that investors have lost confidence in Britain because it will trade less with the European Union and hence will be poorer in the future.

Others insist that the drop in the pound’s value makes the British public poorer already because they can buy less foreign currency and, hence, fewer goods and services abroad. British holiday-makers, says former Bank of England deputy governor Rupert Pennant-Rea, are the first to feel the shock of the weaker pound.

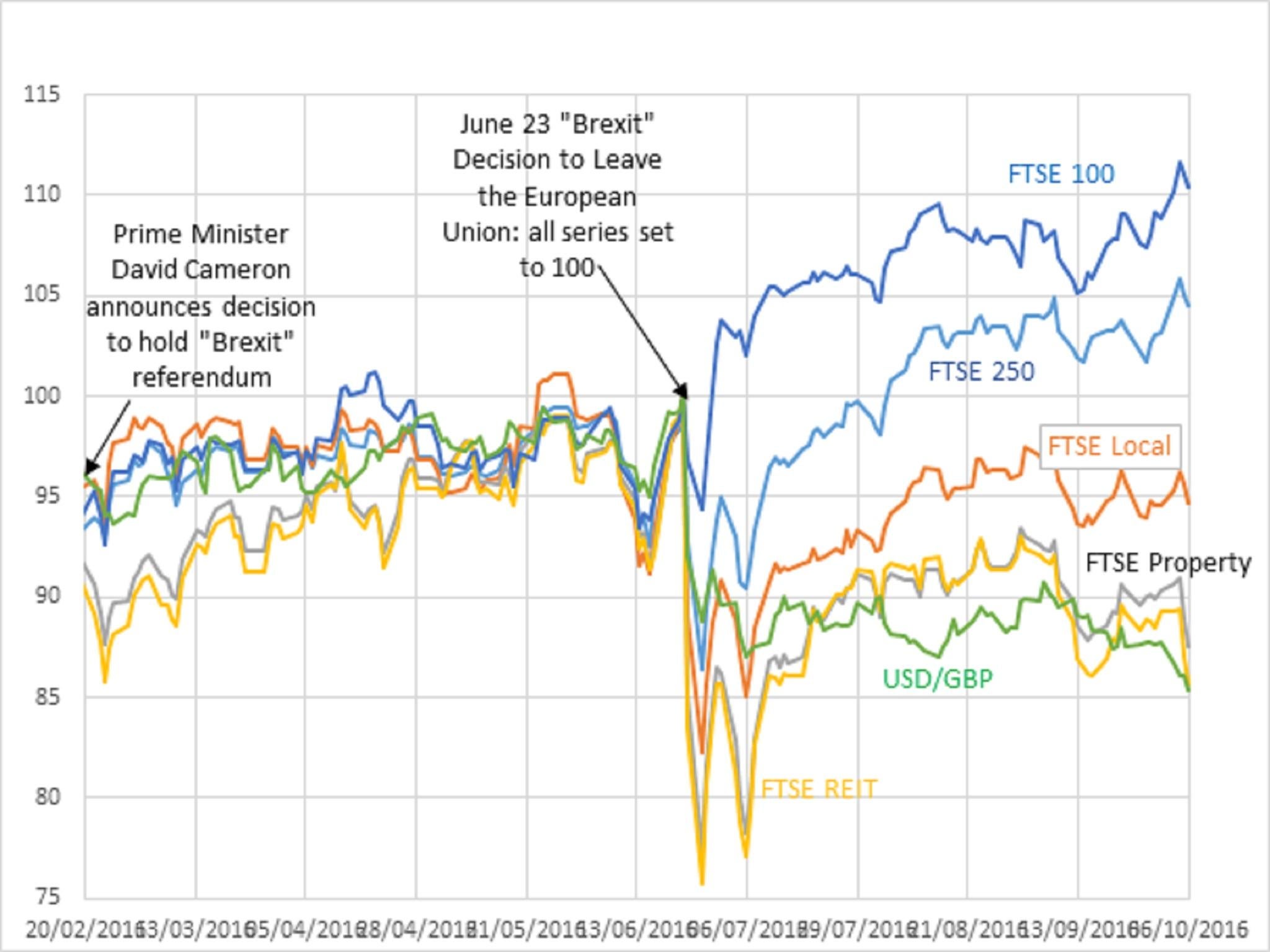

Those who take a more positive view of Brexit point to the smart recovery in stock markets.

FTSE 100 index, comprising large multinationals, is well above pre-Brexit levels. The FTSE 250 – based on mid-caps deriving half their revenues from the British domestic market – is also clearly above pre-Brexit levels.

Even the FTSE “Local” index, whose companies derive 70 per cent or more of their revenues by selling their goods and services within Britain, is now 15 per cent above its post-Brexit lows and within 5 per cent of its pre-Brexit average.

What is going on? A careful look at market indicators suggests that far from being the disaster being portrayed, Brexit may have been a boon.

Composite Market View Gives Thumbs Up for Brexit

To see how Brexit has provided an unexpected dividend, we need to focus on the striking co-movement between the value of the pound and property-related asset prices.

Each time the pound took a sharp downturn, so did property-based assets.

Just as the pound remains well below its pre-Brexit levels, so do the prospects of property values. In the days after Brexit, the only true risk of a broader financial crisis arose on account of frantic withdrawal from property funds.

The composite picture from financial markets tells the following story.

Britain within the European Union became a magnet for speculative international financial capital.

From its unrivalled role as financial gateway to Europe, arose a property-buying frenzy in London and neighbouring districts. British banks channelled foreign speculative capital, and the finance-property bubble became a central feature of the British economy. Believing it was here to stay, even Russian oligarchs and Indian billionaires thought the craziness was a safe investment.

Silently but damagingly, the finance-property bubble also bid up the value of the pound, causing the pound to become overvalued for all other sectors of the British economy. Britain, quite literally, was living on borrowed time.

It is true that with an overvalued pound, the British public could command more foreign goods and services with their currency. But British producers lost competitiveness at home and abroad. Producers’ incentives to invest were weakened, leading to Britain’s poor productivity performance. And that led to a large current account deficit.

As a simple matter of arithmetic, the people of Britain were not richer before Brexit. To the contrary, they were living beyond their means.

People could use the strength of the pound for cheap vacations, but as a country, Britain was spending more than it was producing, and, in the process, becoming more indebted to the rest of the world.

British external debt was 300 per cent of GDP at the end of 2014, about two-thirds of which was short-term debt – debt which could, and did, flee quickly.

The IMF, which does such calculations, reported on February 24, 2016 that the British pound was “overvalued” by possibly 15 per cent, up from fairly valued in 2011.

Things were getting worse by the day. The IMF’s assessment almost certainly understated the problem. Given the sensitivity of a number specifying the extent of overvaluation, the official incentive is to keep it as low as possible. At the time of Brexit, the pound was overvalued by between 20 and 25 per cent.

And so the sense that the British public was richer because the pound was stronger was an illusion. To the extent the finance-property bubble was sowing the seeds of a financial crisis, Britain was living under a dangerous illusion.

Brexit has fortuitously corrected this long-standing distortion in the British economy. It is now easy to see why stock indices are going up. The depreciation of the pound has corrected an overvaluation of the pound, improving the prospects of domestic producers.

Indeed, stock market indices probably understate the improved prospects since the all stock indices, especially the “Local” index, is weighed down by the poor outlook of domestic property companies.

The possible flight of banks and financial companies from Britain should be reason for celebration rather than ongoing hand-wringing. The banking-property complex has been a parasite on the British economy, creating pathologies of financial vulnerability and exchange rate overvaluation.

The Bank of England has been triply culpable. Rather than prick the bubble, Governor Mark Carney celebrated the financial boom. In October 2013, he said was preparing Britain for a financial sector that “could exceed nine times GDP”.

Commenting on Carney’s vision, Martin Wolf warned in The Financial Times: “UK banking is a highly interconnected machine whose principal activity is leveraging up existing property assets.”

Wolf pointed out that only 1.4 per cent of bank loans were to the manufacturing sector. The financial sector’s expansion promoted only its own growth, Wolf wrote; even worse, it exacerbated “the British economy’s debt-induced fragility”.

But the Bank of England seemed unable to act fast enough. Another recent IMF report tells us that lending for buy-to-let homes and commercial properties has been rising at a unsafe pace.

Carney also made the pound’s decline the symbol of the cost of Brexit, and in doing so, he nearly created a self-fulfilling panic. In the weeks leading up to Brexit and after that, his focus on the exchange rate catalysed the narrative that has been uncritically adopted by the financial media and pundits.

And after Brexit, Carney’s drumbeat about the need to protect the economy through lower interest rates and quantitative easing was evidently misguided. It mainly stirred up fear while providing little help to struggling producers. Easier monetary policy has, however, kept the property bubble from deflating even faster.

The political implications are inescapable. The nexus between an ever larger financial sector and a strong pound served a select few who live in London and its neighbourhood. The only people who truly lose from the pound’s depreciation are those who borrowed short-term dollars to invest in long-term property assets.

This “elite” group continues to hold the microphones of policymaking and its words reverberate through the financial press. All these years, however, the strong pound hurt job creation and investment in productivity growth. And those who have long been hurt don’t live in London and don’t hold the microphones.

While several factors led to the Brexit vote, make no mistake, many were protesting that they had been left off the table where the economic pie is divided.

If the pound is about 20 per cent overvalued, then the fuss about the laughably trivial few percentage points increase in tariffs after leaving the European Union is really beside the point.

The pound has depreciated by about 15 per cent since Brexit, and has another 5, possibly 10, per cent go to before it stabilises at around $1.1 dollars per pound.

Rather than imposing a long-term cost, Brexit may, through a more reasonably priced pound, help expand British trade and productivity.

And if Prime Minister Theresa May’s pivot to more investment in education makes real headway, Brexit may have broken the past political lock on policymaking and redirected the economy to a more wholesome and sustainable path.

Ashoka Mody is Visiting Professor of International Economic Policy at Princeton University and former deputy director of the International Monetary Fund’s European and Research Departments

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments