Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s here. The week that economists the length and breadth of the Square Mile have been obsessing over for months has finally arrived. On Wednesday, the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee will unveil some form of “forward guidance” on the future path of interest rates.

It’s no secret that the new Governor Mark Carney – with the backing of the Chancellor – wants to communicate to financial markets that policy rates will remain at their present historic low levels of 0.5 per cent for a few more years yet in order to keep monetary conditions supportive of the economy. He does not want market rates, in the form of rising 10-year gilt yields, to choke off growth.

That much we know. What is unclear is what “intermediate thresholds” Mr Carney, below, and the MPC will attach to this forward guidance. What would prompt a tightening of monetary policy by the central bank? A fall in the unemployment rate target perhaps to 6.5 per cent? That’s what the Federal Reserve in the United States did. Will it be a judgement from the MPC about the level of spare capacity left in the economy? And will there be a “knockout” if inflation rises above a certain level? Or perhaps the MPC will opt instead for a simple time commitment, with interest rates to be kept on hold until at least 2016? Mr Carney implemented something along these lines when he was governor of the Bank of Canada during the financial crisis.

City analysts have been writing with varying levels of confidence about what monetary policy parameters we are likely to get on Wednesday. But they are just guessing. And it strikes me that this speculation misses a more important question: will forward guidance actually work in influencing market interest rates?

There’s an irony that’s been missed in all this. George Osborne has spent much of the past three years boasting that ultra-low gilt yields are a reflection of the credibility his austerity programme has won among investors. By this logic, of course, the recent rise in yields must mean that his fiscal credibility is on the slide.

In fact, the original Osborne analysis was faulty. There is no compelling evidence that interest rates in a country like Britain, which has full control over its currency, are much affected by fiscal policy. Empirical studies show the two major influences on gilt yields are, rather, the prospects for economic growth and monetary conditions in the world’s largest economy, the United States.

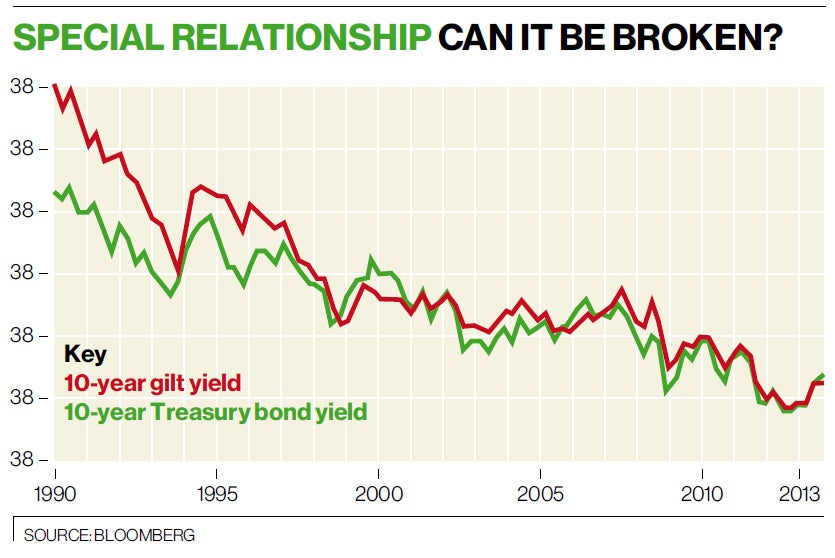

Yields fall when markets expect low growth. And vice versa. Ten-year gilt yields have risen in recent months because the UK’s economic outlook is finally improving after three years of stagnation. There was a similar rise when the economy was last growing in 2010. But they have also risen because the American economy has been kicking into a higher gear. Since the turn of the Millennium, yields have followed the yield on US Treasury bonds remarkably closely, as the chart above shows.

This poses a difficulty: market interest rates could rise quicker than justified by domestic British conditions. Mr Carney’s hope is that he can successfully decouple gilt and US Treasury bond yields in a bid for monetary independence. But there are grounds for scepticism over how easy this will be. The Bank of England actually gave some informal forward guidance to markets after July’s MPC meeting when it released a statement saying that the recent rise in interest rate expectations was “not warranted”. But this had almost no impact on yields. What did, however, have an impact was a dovish statement by Ben Bernanke later in the month on the pace of withdrawal of monetary stimulus by the Federal Reserve.

The better-than-expected American GDP growth figures last week, and another statement from Mr Bernanke, also showed up very clearly in both Treasury bond and gilt yields. The selection of the next Federal Reserve chair to replace Mr Bernanke in September (and the new central bank supremo’s views on US monetary policy) may well matter more for UK monetary conditions than Mr Carney’s guidance.

It is possible that explicit guidance from Threadneedle Street will sever the “special relationship” between gilts and Treasuries. But it’s difficult to be confident.

My own view is that, despite these doubts, forward guidance is worth a shot. Recent experience has rammed home the lesson that financial markets do indeed sometimes misprice things. They can get ahead of themselves. And if markets do push up gilt yields fast it certainly wouldn’t help the economy. Borrowers would find payments rising. Fragile consumer and business confidence could be crushed. If guidance can act as a sort of insurance – a Carney “put” if you like – that the Bank will keep monetary conditions lax until the recovery is firmly established, that would be welcome.

That said, it will, at best, be insurance rather than a genuine stimulus. Analysts are getting excited about the speed of the recovery, especially since the Office for National Statistics reported growth of 0.6 per cent in the second quarter. But GDP remains still 3.3 per cent below the level of early 2008 and output per head is an abysmal 7 per cent lower than it was five years ago.

To recover these many acres of lost territory the economy needs to maintain this growth rate for an extended time. And I have doubts about how sustainable this recovery will prove while real wages are still falling and foreign demand for British exports remains weak. At the moment we have growth in spending being powered by households reducing their savings rates. Can that last?

To turn this recovery into a proper rebound (of the sort that we should be experiencing in the wake of the massive collapse in output of 2008/09) there needs to be a boost to domestic demand that raises wages and business investment. The macroeconomic policy mix required is more quantitative easing combined with a pause in state austerity and a boost to infrastructure spending, as recently advocated by the International Monetary Fund.

Verbal guidance is all very well, but actions from policymakers, in the end, speak louder than words.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments