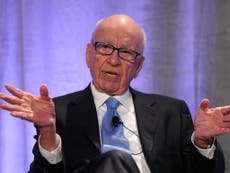

Rupert Murdoch has left the stage but not the building – not by any stretch

As the billionaire media baron announces his retirement from running his global empire, Chris Blackhurst explains that while he has handed over the reins of Succession to eldest son Lachlan, he will still be lurking in the wings — and threatening to walk the floors (whether the new boss and his employees like it or not)

Just like that, he has gone. Rupert Murdoch has left the stage.

He is ceasing to play an active role in his media empire, leaving it in the sole charge of son Lachlan, and moving upstairs.

The old toughie has finally conceded to the passage of time and at 92 (92!) he is becoming chairman emeritus of News Corporation and Fox. After more than 70 years, he is calling it a day.

The mind is immediately drawn to his exchange with Frank Giles, who was told he was no longer editor of Murdoch’s Sunday Times in 1983 – this, after the Hitler Diaries scandal. Until his retirement two years later in 1985, Giles would be “editor emeritus”. He asked Murdoch what his new title meant.

The mogul said, “It’s Latin, Frank. E means ‘exit’ and meritus means you deserve it.”

Presumably, that does not apply in the case of the multi-billionaire patriarch, business genius and major influencer (some would be far less polite than that) of our time. It’s impossible to imagine him taking a back seat and not phoning one of his minions at some godforsaken hour with a thought, a steer, an instruction.

He is someone who has breathed, swallowed and infused the thrill, the adrenaline, of making newspapers and with it, the crossover into high-level politics, for all his life. Ever since his father, Sir Keith, died when Murdoch was just 21, and he took over the family business, he has been immersed in the generation of content, first in papers, then in broadcasting, film, book publishing and latterly, digital. He did not just manage his myriad titles, products and channels, but drove and whipped them, with irresistible, relentless force.

No one anywhere in the industry matched him for sheer determination and audacity. He transformed the media, sports and movie landscapes, introducing subscription TV services to the UK, aggressively bidding for football rights and revolutionising the finances of the top-level professional game. He challenged the grand, imperious Hollywood film studios, exhorting his journalists to pursue exclusive stories with a zeal that – in some instances in the UK – gave way to illegality by hacking mobile phones and invading privacy. Throughout it all he displayed a pugnacious bias that blew apart the hitherto accepted boundaries of journalistic objectivity.

Always, his approach was marked by a ruthless pragmatism. Direct and forthright in manner, many of his titles displayed the same front-footed, in-yer-face (as his tabloid papers might say) style. In person, he is not loud or brash. Murdoch is quiet and reserved, preferring to keep his counsel before speaking his mind, delivering his thoughts slowly but to the point.

His specialty was not playing by the accepted norms, unafraid to upend traditional ways. Invariably, he was driven by commercial self-interest, making himself and his family formidably wealthy.

In Fleet Street, he parachuted into an industry that was in hock to the trade unions, bedeviled by restricted practices, including closed shops, to the extent that newspaper management never knew if editions were going to be printed on time, if at all. Murdoch’s solution was typically audacious and resolute. In total secrecy, he had constructed a new printing plant at Wapping, containing the very latest computerised editorial technology.

Then, in 1986 he sprung his surprise, announcing he was moving his News International papers (The Times, The Sunday Times, The Sun and News of the World) there and refusing to recognise the print unions. Cue a strike call, and from Murdoch, the serving of 6,000 dismissal notices on those workers taking part. This sparked what became, along with the earlier coal miners’ dispute, a defining industrial struggle of the era.

Twelve months of mass picketing, heavy policing, nightly violence, multiple arrests and injuries, culminated in total capitulation for the unions. Murdoch stared them down, surrounding his plant in barbed wire and forbidding security, and bussed in journalists and staff. In the end, in return for what was little more than a token financial settlement, they caved in. Ever since, Murdoch, a fierce defender of capitalism, although never a dogmatic right-winger (witness his support for Tony Blair) was a hate figure for the left.

The Wapping riots and union defeat transformed newspaper production and hastened the demise of the old Fleet Street, as other companies moved out, to modern, purpose-built premises. One beneficiary, ironically, was The Independent, the new paper that was able to take advantage of lower production costs and hire many of those “refuseniks” from The Times who refused to cross the picket lines.

Wapping was a bold move of the sort that defined Murdoch. He was the proprietor who, against his natural puritanism but because he was persuaded it would drive sales, launched Page 3 in The Sun, showing bare-breasted women. Neither did he always approve of some of his tabloids’ more lurid headlines and stories, but he let them be.

What he did appreciate was an anti-establishment irreverence. He went to Oxford University to study PPE but delighted in being “the outsider” – in the UK, US and even in his native Australia.

He was no respecter of title or status and was fazed by no one. He liked to position himself as on the side of the ordinary person, railing against privilege (even though his own background was one of immense advantage), incompetence and hypocrisy.

That attitude extended to his newspapers, especially in the UK with The Sun and News of the World. Their forever poking approach, laced with ribald humour, changed what until then had largely been a conservative and po-faced Britain. Pre-Murdoch, there were totems that could not be challenged, post-Murdoch nothing was untouchable.

It was Murdoch who, after his best-selling Sunday tabloid was placed in the middle of the hacking storm, simply closed down the News of the World, rather than have it drag down the rest of his corporate interests in the UK and worldwide, and his own personal reputation. It was a financially costly stroke, but he did it – without preamble he pulled the plug.

Has he retired, really? Only this summer, Sir Keir Starmer was chuffed to be awarded a prime slot on the sofa next to him at Murdoch’s annual drinks party. Westminster tongues immediately began wagging that Labour was to receive the nod over the Tories in the forthcoming UK general election.

A previous contestant, John Major, was granted a 30-minute audience ahead of the 1997 ballot. It was a troubling period for Major, the then prime minister. Murdoch’s papers had been calling for a change of Conservative leader and they were heaping praise on Labour’s Tony Blair. According to government documents, Major (the premier, don’t forget) was instructed to show “supreme confidence and clear vision” in selling himself to Murdoch. It didn’t work.

After the encounter, Murdoch’s Sun, then the biggest-selling paper in Britain, came out for Labour, proclaiming on its front page that Blair was the “breath of fresh air” that the country needed, while the Tories were “tired, divided and rudderless”.

So, it now falls to little known, untried, untested Lachlan. Finally, it seems, Murdoch has made up his mind and chosen which one of his children is to succeed. As in Succession, the other siblings step aside. In this version it is Kendall, the “eldest boy” of Logan Roy, who has got the gig. How it will pan out, remains to be seen.

In this country, Sir John Moores, a spring chicken compared to Murdoch, returned to the breach of Littlewoods in 1980 at the age of 84, having seen profits plunge at the family football pools, retail and catalogue business. Do not rule out Murdoch doing the same.

Murdoch has departed but he has not left the building, not by any stretch. As his valediction makes clear: “In my new role, I can guarantee you that I will be involved every day in the contest of ideas. Our companies are communities, and I will be an active member of our community. I will be watching our broadcasts with a critical eye, reading our newspapers and websites and books with much interest, and reaching out to you with thoughts, ideas, and advice. When I visit your countries and companies, you can expect to see me in the office late on a Friday afternoon.”

As if that was not warning enough, there came this sentence: “I look forward to seeing you wherever you work and whatever your responsibility.” How his executives must be relishing that.

In Murdoch’s case, E definitely does not mean ‘exit’.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments