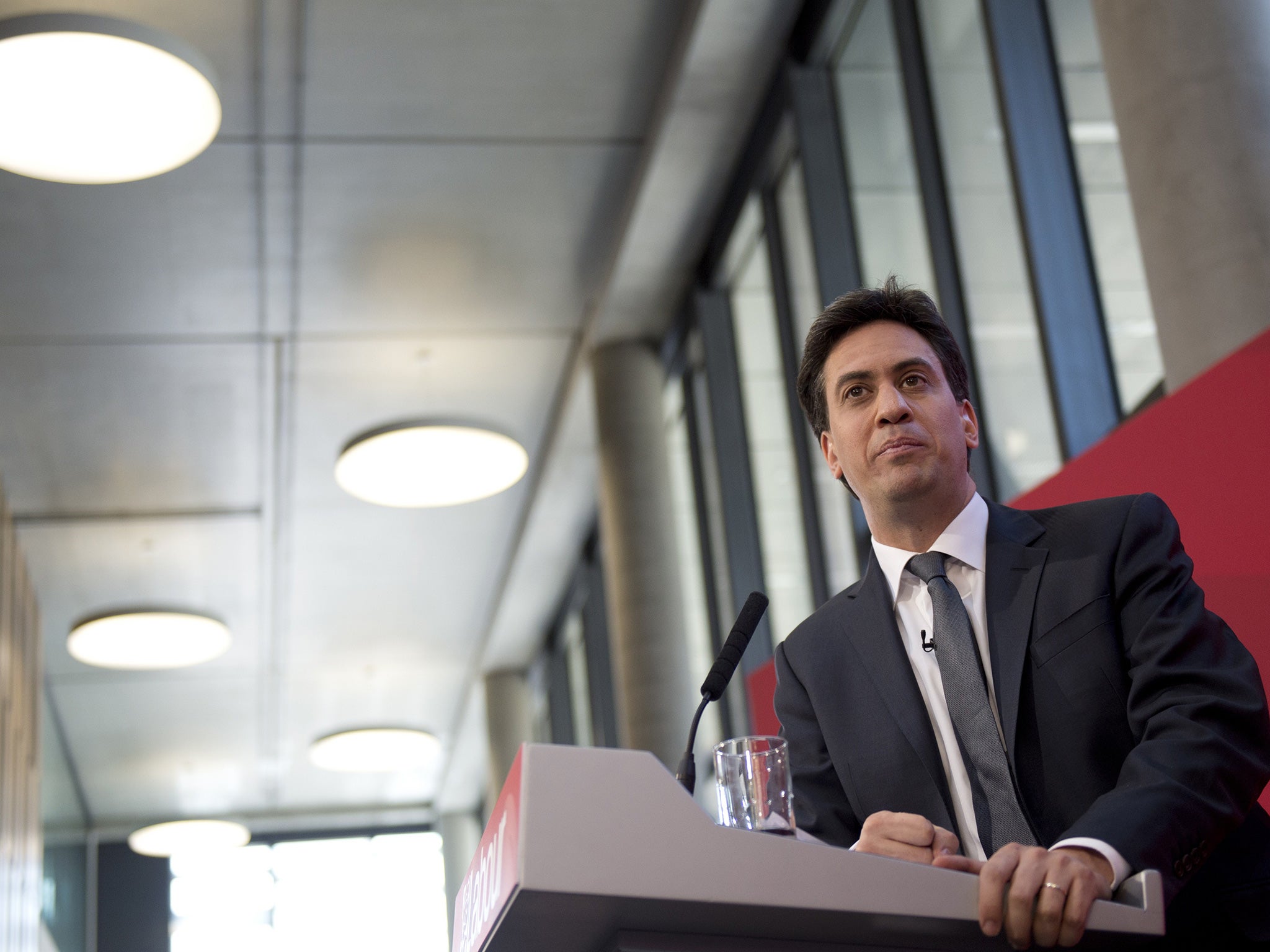

It's not Miliband who is worrying the banks, it's our future in Europe

My Week

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Will the last business to leave Britain if Labour and the SNP hold power on 8 May please turn off the lights?

It is tempting to interpret HSBC’s review of whether it should move its headquarters out of London and out of the UK as the country’s biggest company making plans to go before the interventionist Ed Miliband takes the reins. Another reaction, from the anti-banks brigade, would be “good riddance”.

Both are wrong. It is true that Labour has plans to shake up the industry, by capping the market shares of the biggest lenders and introducing a network of regional banks. The tax on bankers’ bonuses would return.

Of greater concern for Douglas Flint, HSBC’s chairman, is the rising cost of regulation – something that neither party would alleviate. HSBC has already committed to relocating its UK retail and commercial banking businesses from London to Birmingham, as part of ringfencing rules that will separate them from riskier investment banking activities. So minor is the UK bank within its empire that HSBC might just as easily sell what was the Midland franchise. Remember, it only moved its HQ to London just over 20 years ago at the instigation of City regulators when it acquired “the listening bank”.

Political leaders will be listening now. The price of entry to London’s financial district has soared – especially for those that call the capital home. The banking levy – devised by George Osborne as more equitable than a bonus tax – cost HSBC £740m last year. Since the Chancellor hiked the rate in the Budget to bring in £3.6bn next year, HSBC could be chipping in £1bn annually.

That’s just about bearable, and it can cope with the public hatred stoked by HSBC getting hauled over the coals, quite rightly, for its abject failure to stop dodgy dealings at its Swiss private-banking unit. But if London is no longer the place from which to trade into Europe, the scales start to tip. Well-paid jobs might as well be stationed elsewhere.

HSBC has threatened to leave London before, prompted by conversations with international shareholders who see that all the bank’s growth prospects are in Asia. It cannot have escaped Tory high command that the “neverendum” leading up to an in-out vote on European Union membership could be the biggest anti-business measure of all.

Bosses can’t stand still, as Marathon runners will see

Hard-driving business leaders like nothing better than pushing themselves in their leisure time as much as in the office. It must be why so many are lining up tomorrow to compete in the London Marathon.

I joined Jayne-Anne Gadhia, the boss of Virgin Money, on a training run this week to see how her preparations are going. Ms Gadhia insists she is a novice, even though she has a couple of Great North Runs under her belt and the company has sponsored the race since 2010. But even if her race time is unremarkable, that is not the point. She will be remembered as the person who persuaded the Bank of England’s Governor Mark Carney to run among a pack of bankers raising cash for Cancer Research UK.

Also lacing up her trainers on Sunday will be Dambisa Moyo, the economist who sits on the board of Barclays and brewer SABMiller. At a breakfast hosted yesterday by the investors’ club Pi Capital, she shared her thoughts on what chief executives can learn from marathon running.

First of all, the middle of the road isn’t such a bad place to be, even if it is where runners jostle for position; the temptation to veer into new territory is risky if it means the going gets bumpier. Ms Moyo adds that the best-laid plans need to factor in uncertainties, such as the winds that dogged her New York marathon attempt.

Adapt fast to changing circumstances is a message that works as well on the streets of London as it does in the boardroom.

A big stamp of approval for UK high-tech contenders

One sign that the UK’s technology scene is maturing is the amount of funding its brightest stars can attract – and who is writing the cheques.

Funding Circle, the peer-to-peer lender, attracted $150m (£100m) of investment this week, giving it a value close to $1bn. The company knows all about small-business expansion because it matches cash from retail investors – who are looking for a better rate of return than rock-bottom interest rates can offer – with entrepreneurs who aren’t getting the deal they want from conventional lenders.

Most eye-catching about the announcement was that an investor called DST has jumped on board. The firm is run by Yuri Milner, a Russian who was briefly regarded as foolish when he skipped ahead of long-established Silicon Valley names to sink $200m into Facebook in 2009. At that time, the social media company was worth a heady $10bn; today, it’s 20 times as much. DST didn’t stop there: Twitter, Spotify and another British start-up, Farfetch, followed. Now it is seen as a kitemark for the ones to watch.

I remember meeting Mr Milner in Claridge’s, when he set me the challenge of interviewing him without using any of his quotes. He might be guarded around the press, but entrepreneurs have obviously taken to him. One of the main reasons is that his cash comes along at just the right time, so they can resist going public for longer. Mr Milner demands very little, other than that they keep doing what they are doing. In a world where British tech start-ups are often guilty of selling out their great ideas too soon, that can only be a good thing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments