‘Success’ in the eurozone is nothing to write home about

Economic View

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Today will be pretty much the last throw of the dice for the European Central Bank. We don’t, of course, know the details of what its president, Mario Draghi, will announce but it will presumably include a notional interest rate cut and a commitment to extend the quantitative easing (QE) programme indefinitely. There will also be some surprise and we will just have to see whether the ECB can exceed expectations. But in reality it is at the limits of what can be done by monetary policy.

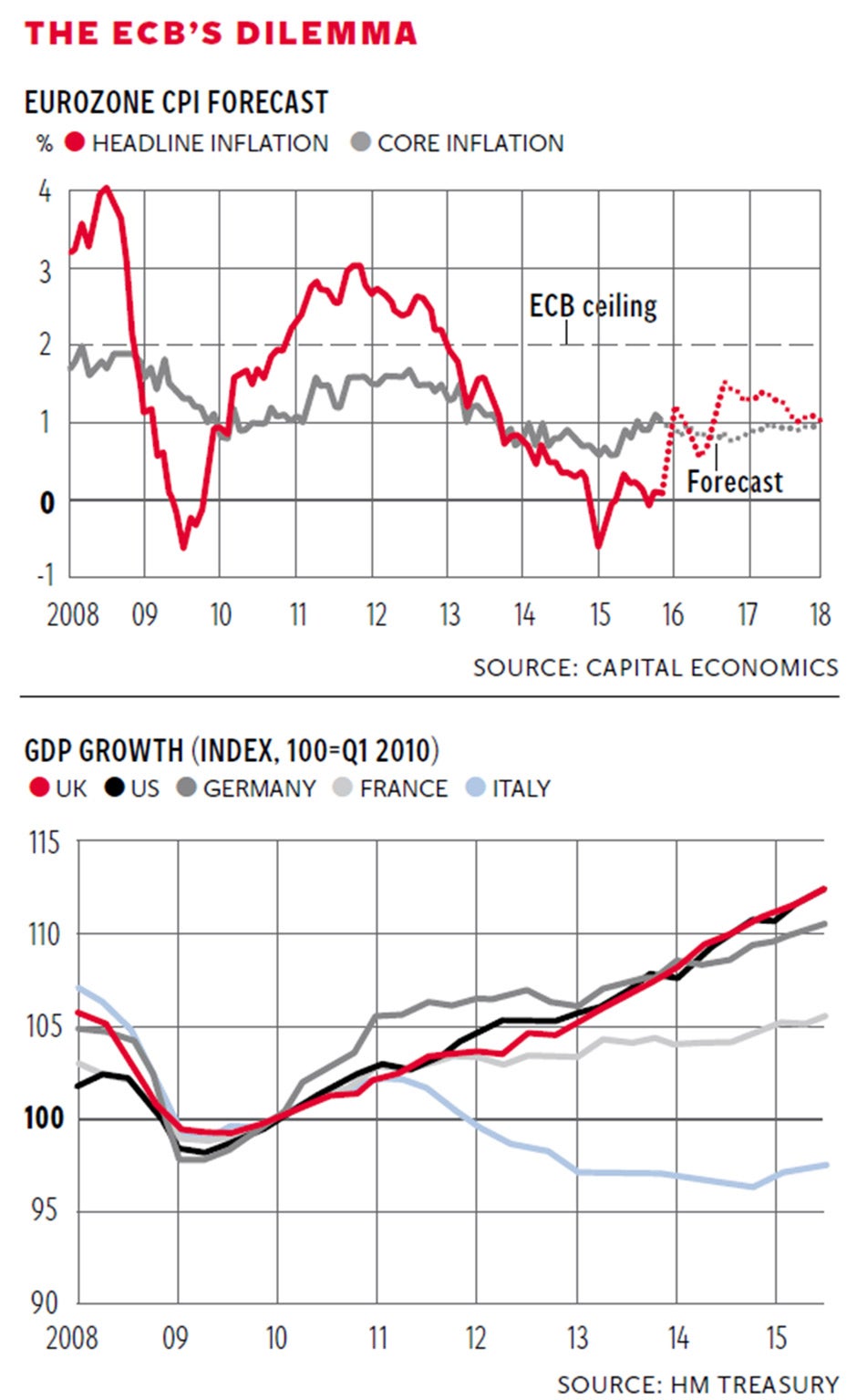

The two graphs show the justification for further action and the reason why it is likely to be ineffective. On top is the inflation performance for the eurozone. The requirement on the ECB is to keep inflation below but close to 2 per cent. (It is a different mandate from that for the Bank of England, which is supposed to keep inflation close to the 2 per cent level, but which is symmetrical on either side of it.) As you can see the core inflation rate has remained not just below 2 per cent but well below it, while the headline rate is currently near zero.

That gives full justification for some effort to boost inflation across the region and one effect of QE should be such an increase, though in the first instance QE is likely to boost asset prices rather than current prices. The projections in the graph (left, top), from Capital Economics, suggest that the core rate of inflation will remain well below the 2 per cent ceiling.

The bottom graph comes from the Chancellor’s Autumn Statement and shows how the UK and US are currently leading the recovery. But the point of showing this graph here is not to crow about the UK recovery vis-à-vis others, but rather to show the divergence within Europe.

Germany has shown solid growth, stronger in the early years than either the US or UK, but France and especially Italy have disappointed. So the dilemma for the ECB is to frame a monetary policy that is appropriate both for the slow-growing parts of the eurozone, especially Italy, and the faster-growing parts, especially Germany.

Looking at that graph you can grasp that a policy that is appropriate for Germany will not be right for Italy, and vice versa. Take property: Germany is already experiencing a real estate boom, especially in hotspots such as Berlin, and the more money the ECB creates the more is likely to flow into Germany; but in Italy demand for property is constrained by five years of stagnation and continuing emigration of its young people. As a result the property market remains moribund.

It gets worse. What that graph shows is differing growth within Europe. What it does not show is the payments’ imbalances this leads to. Germany now has a current account surplus running at more than 8 per cent of its GDP. Italy has a smaller surplus, a bit below 2 per cent, while France is in rough balance. The eurozone as a whole is in surplus of around 3.5 per cent of GDP. So not only does Germany ideally need a higher exchange rate for the euro, while France does not, the eurozone in general arguably needs a higher exchange rate if its surplus is not to grow further.

So what will happen? The decline of the euro against the dollar probably still has some way to run and the market expectation is that the announcement today will give it a bit more of a downward kick. If that is right, the eurozone current account surplus will grow and the German surplus will move up still further. Monetary policy cannot by its very nature correct imbalances within the eurozone.

And so to the huge question: will it boost overall eurozone growth? Monetary policy is so inexact in its effect that it is hard to know quite how much weight to attribute to it. As noted above, the first bout of QE earlier this year does seem to have had some impact on asset prices. European shares have done well in euro terms, though rather poorly when expressed in dollars, or even a weighted basket of world currencies. And property has been uneven. Bond markets, however, have responded well, driving down sovereign yields particularly of fringe countries.

But now it is hard to see much more impact on asset prices, so the main way in which more QE will boost the European economy will be through the exchange rate. The euro is already undervalued and the question is whether an even greater undervaluation will drive demand.

My guess is that it will – a bit – but the main beneficiary will be Germany, which will become ultra-competitive, rather than the Mediterranean countries where help is needed most. If this is right, Germany will have growth of around 1.8 per cent next year, spot on the estimate from Consensus Forecasts, which does a tally of what the main forecasters are predicting. That should be enough to lift eurozone growth to around 1.5 per cent – not great, but acceptable by recent standards. Even Italy will grow at above 1 per cent, just enough to pull down unemployment a little.

So 2016 will become a year of modest success for the eurozone. The long-term imbalances will remain, perhaps worsen. The two economies currently still in recession, Greece and Finland, will continue to find growth elusive – for Greece in particular it will be another miserable year. But Mr Draghi will be perceived to have performed his confidence trick again, nudging the region into a slightly stronger recovery.

That, at least, is the sensible mainstream view. But come back to the point at the beginning. This is the last throw of the dice. The eurozone, taken as a whole, will remain a weaker economic performer than the rest of the developed world, bar Japan. The US and UK will continue to outperform it. And the non-euro countries of the European Union will grow faster than the eurozone members. So the “success” of the ECB should be seen in this context.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments