Paris attacks: It's absurd to say terrorism is good for the economy, but there will be silver linings

Economic View

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What has happened in Paris is principally a political and human story, rather than an economic one. But there are economic consequences, not just directly from the outrage itself but also from the response to it of European governments and the European Central Bank. Perhaps surprisingly, those consequences are as likely, on balance, to be positive as to be negative. It would be offensive and absurd to suggest that terrorism is somehow good for the economy, and there will be considerable and inevitable financial costs as well as human ones. But there will be silver linings. If you doubt that, remember how the IRA bombing of Manchester led to a rebuilding and a revival of the city centre.

Start with the obvious identifiable costs. There will have to be more resources put into public safety and, in the case of France, it looks very much as though the European constraints on deficit financing will be eased. There will also be a short-term hit to the level of economic activity as consumers pause their spending. Some sectors, notably travel and tourism, will also be big losers, for a hotel bed or an airline seat that is not sold cannot be stored and sold again later.

But it is important to note that, in terms of total public spending, the costs of fighting terrorism are quite limited. In the case of the UK, the doubling of spending against cyber crime to £1.9bn a year by 2020 has to be seen in the context of total defence spending of £45bn a year and total spending of more than £700bn. The figures are disputed but it has been estimated that Britain has spent £33bn on overseas military campaigns in the past 20 years. Wars are expensive; security less so.

What about the impact on economic activity more generally? This would be serious if terrorism depressed consumption for a prolonged period, but the evidence suggests otherwise. There was some short-term reduction in activity following the 7/7 attack in London in 2005, but things quickly bounced back. Even the much graver blow of 9/11 in New York in 2001 depressed activity for only a few months. You have to accept the possibility that these Paris attacks may be different – that there is a longer-lasting effect on Europe more generally – but there is no evidence of that as yet.

Might the additional security measures that will have to be taken, including some return of border controls, be the thing that makes the difference? Physical controls won’t have any significant impact. Look how the disruption at Calais has failed to dent trade between Britain and Europe. It has added to costs a bit and there is, of course, the humanitarian concern – but, from a trading point of view, the economic impact has been modest.

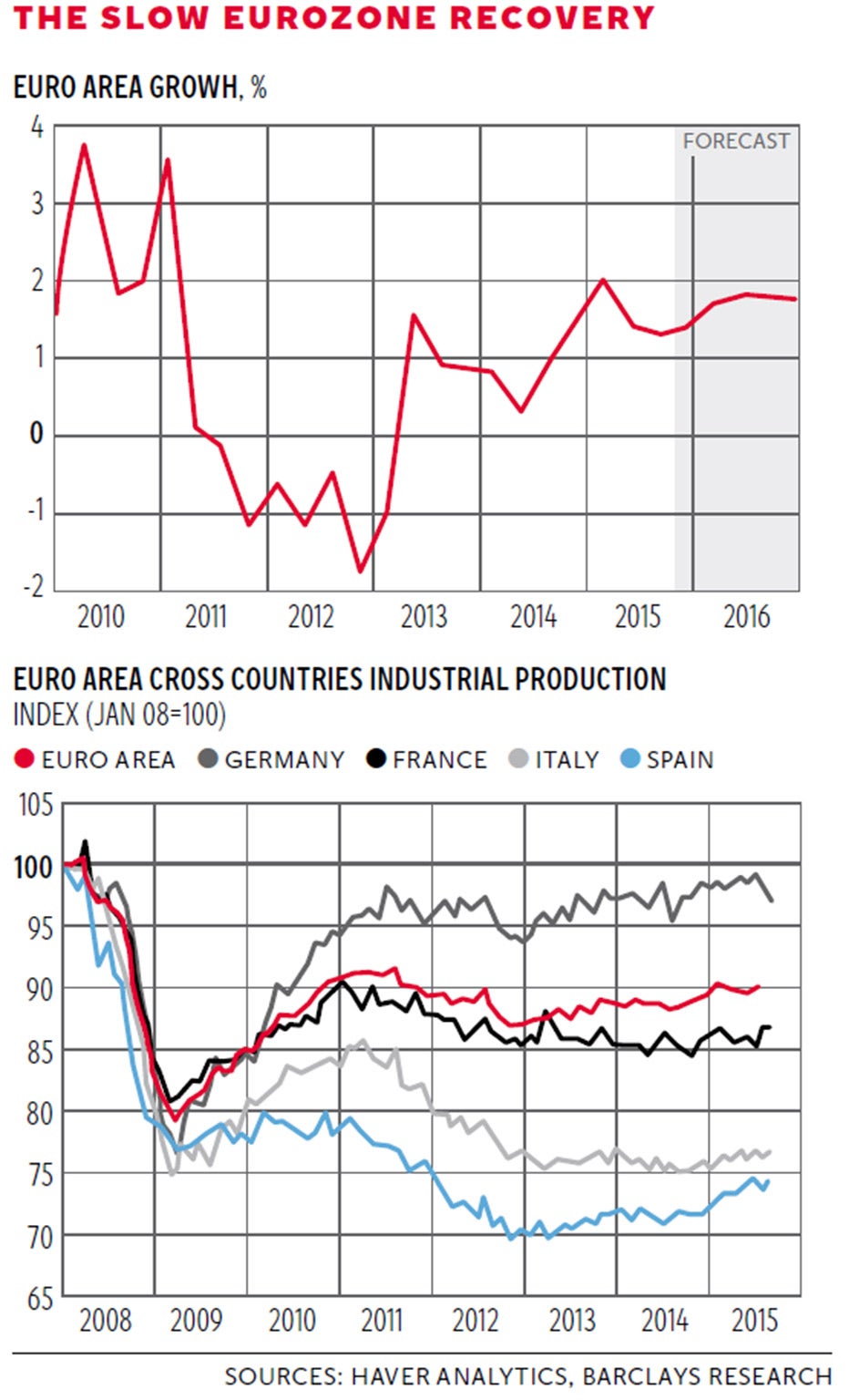

We have, I am afraid, to accept that there will be more attacks. Were European consumers to restrict their travel and other spending, not so much because of physical restrictions but because of more general fears about the future, then maybe there will be a general depression on consumption and hence on growth. All one can say is that this does not seem to have happened elsewhere, including the UK during the period of IRA bombings. If you look at the European economy in general over the past five years, it managed to have a second recession after 2008-9 that had nothing to do with external shocks such as this one (see top graph).

What about the economic positives? There will be some loosening of fiscal policy, but I think that will turn out to be marginal. Monetary policy, on the other hand, will remain looser for longer. Perhaps the greatest problem of the eurozone economy is its unevenness. Germany has managed a decent recovery in industrial production, as you can see from the bottom graph, but the recovery in France has stalled and those of Italy and Spain have been most disappointing. The question really is whether an even looser monetary policy will help the laggards most. There does seem to be a bit of evidence that Italy and Spain have benefited more than France from the ultra-easy policies of the ECB, and it is at least possible that the yawning gap in eurozone performance exemplified in that graph might narrow a bit further.

There is a further prize. A shock such as this makes governments throughout Europe think about economic policy more generally. If you ask why some young people feel so excluded from the mainstream of society, you are forced to confront the levels of youth unemployment and the reasons for that. This is a problem for France but also for Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Greece – indeed, in varying degrees, for more than half of the eurozone members. If governments were pushed not just into spending more on security but also on the causes of youth disenchantment and disconnection, you could see what happened in Paris as a catalyst for a wider shift in policy.

One of the most frustrating aspects of the European economy is its failure to use the human resources it has available. An ageing continent cannot afford to use a scarce resource, its young, wastefully. Germany, the strongest economy on the continent, gives some pointers, both in its education and in its flexible working conditions.

As far as the former is concerned, thanks to its long-standing apprenticeship system, it manages to have half the level of youth unemployment of the rest of the eurozone. As for flexible work, while its mini-job solution to rigid labour laws has been much criticised and it would have been better to ease those laws rather than create loopholes that enable employers to get round them, at least it creates jobs. So, too, does the UK, which now has the highest labour participation rate in its history.

The big point here is that shocks, even dreadful ones such as this, sometimes prod governments into policies they were considering but had yet to build the support to put them into action. The eurozone needs to lift its economic game. The sub-2 per cent growth outlook of the top graph will not be enough to pull down unemployment much, and it is still in double digits. The best hope is that this shock will push Europe to do better.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments