It is bond yields, not political fallout, that should be worrying us now

Economic View

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I am worrying about something. No, not what will happen in the UK in the next few days, though maybe that should be a worry. It’s that there is a timebomb ticking away in the bond markets, with the unwinding of QE, particularly in Europe, being more difficult and destructive than most people now appreciate.

There are, as is usual after any long bull equity run, quite a few warnings around of a forthcoming crash in share prices, and there is in any case a good chance of a correction during the summer. But what has been happening in the bond markets is rather different. Bond prices are not as interesting as share prices: a 10-basis point move in 10-year German bund yields makes a worse headline than a 3 per cent rise in the share price of HSBC when it says it may move its headquarters out of London. But bund yields have an impact on the cost of mortgages across the eurozone (and to some extent here), whereas the price of HSBC shares really has not that much effect on anything.

The easiest way to get one’s mind round what is happening is to start with 10-year government bond yields. US treasuries yielded 2.2 per cent and UK gilts just under 2 per cent. Many of us think these are far too low; what is inflation going to be over the next 10 years? Say 2 per cent. So an investor would get no real reward at all. But while these are far too low, they are not ridiculously low. For that you look at German bunds. Yesterday they yielded just over 0.5 per cent. At that level you are bound to lose money and would be far better with just about anything else: equities obviously, or maybe buying a flat in Berlin or even Athens, the latter being rather cheap right now.

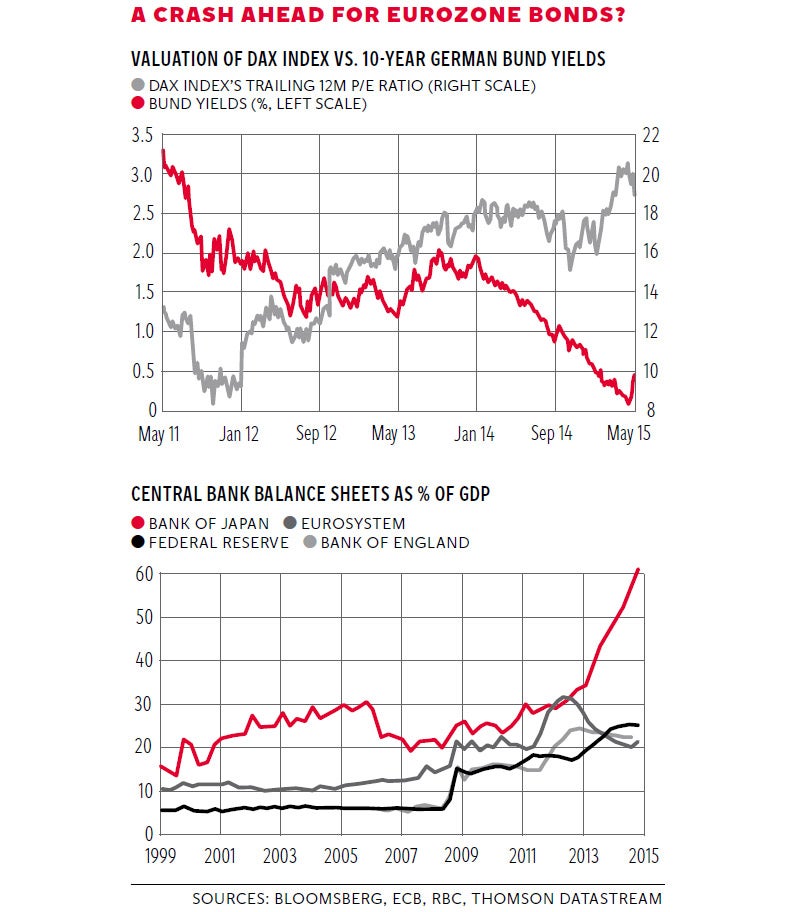

Actually bunds yielding 0.5 per cent represent some return to sanity compared with yields in the middle of last month. As you can see from the red line in the top graph, yields dipped to 0.1 per cent for a short period. If you were nutty enough to buy at that level you would have lost quite a lot of money by now.

You could argue that German yields make sense if you think the country will dump the euro and return to the deutschmark, for investors would make a currency gain. But that is some way off and in any case the argument would not apply to French or Italian bonds, yielding 0.9 per cent and 1.9 per cent respectively. So ask yourself this: which country is more likely to be able to pay its debt back in 10 years’ time, Italy or the US? Not many people would say Italy. Yet Italian yields are lower than US ones. This cannot be right. So why is this happening? There is one possible answer, which is that people believe that Europe will have a long slump akin to that of Japan (10-year Japanese yields were 0.3 per cent yesterday). But that does not really square with what has been happening to share prices. As you can see in the top graph, German shares are on an extended price/earnings ratio, having peaked above 20 earlier this year. You would not have such high share prices if you expected an extended eurozone slump.

The best answer to this puzzle is that it is a response to the European Central Bank’s QE programme. If you say you are going to buy shedloads of bonds the price goes up – and the yield mathematically goes down. Yields were already falling but were given a further push down last September when the ECB unveiled its plans. Europe joined the party established by the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England. You can see how central bank holdings of government stock have risen relative to GDP over the past 15 years in the bottom graph. The US, UK and the eurozone are all in pretty much the same position at between 20 per cent and 30 per cent of GDP, while Bank of Japan holdings are off the graph at more than 60 per cent.

So you could argue that ECB holdings are not excessive by global standards; indeed they are lower than they were at the height of the last eurozone crisis in 2012. But what if our perception of normality is flawed?

BNY Mellon has made an important observation in its market commentary about the so-called “Greenspan put”. This is the idea that whenever markets hit trouble the central banks will bail them out by cutting rates and/or printing more money. This happened after the Wall Street crash in October 1987, the LTCM crash in 1998, the dot-com crash and of course the most recent one. The bank says: “Given this well established cycle, what is perhaps most alarming of all is quite where some financial markets have managed to reach. Most obviously, the extraordinarily low levels of yields seen in European bond markets in recent weeks is already ringing alarm bells …”

It goes on to note that when the market turns, as it may already have done, that will have knock-on effects on other asset markets. To put it another way, if European bond prices crash, other bond prices are likely to fall as well and I suppose you could go on to argue that equity and property markets are likely to be hit, too.

This will affect us, and may turn out to be more important than the political fall-out tomorrow. Actually I don’t think UK shares are that bad value right now, for they are on less demanding ratings than German or US ones. The FT100 index also represents global earnings, rather than UK ones. But it is quite plausible that our 10-year gilt yields will double to 4 per cent over the next few years, maybe more, and that would have a pretty big impact on government finances as well as the property market. It is some comfort that the European financial system faces even greater dangers, but only some – for unfortunately we will get caught in the crossfire.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments