Oil dividend: how we should all benefit from crashing prices

Economic View

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When the Cold War ended there was talk of there being a “peace dividend”, a bonus to living standards that resulted from governments spending less money on defence. In recent months a similar argument has been debated: is there an “oil dividend” from the fact that consumers need to spend less of their income on energy?

The commonsense answer to that question is that it must be so. If it costs £30 instead of £50 to fill up the car at the weekend, that leaves £20 to be spent on buying other things. That increases real living standards. Oil-exporting countries do suffer (and oil-exporting regions within a country, such as the area around Aberdeen, take a hit) but the world as a whole benefits. Because the fall in the price of oil affects other costs, including that of chemical feedstocks as well as other sources of energy, these benefits go far beyond the immediate impact. Most people get a real increase in their living standards, but from lower prices rather than from higher incomes. The increased volume of consumption further drives growth, increasing employment elsewhere, in a positive feedback loop.

The trouble is that this positive loop does not seen to be working, or at least not very well. Almost the reverse seems to be happening, with the fall in the oil price regarded as some sort of precursor of a wider economic downturn, or at least as an indicator of a sharper than expected slowdown in the world’s largest oil importer, China. So instead of celebrating the decline in the oil price, people seem almost to fear it. What’s up?

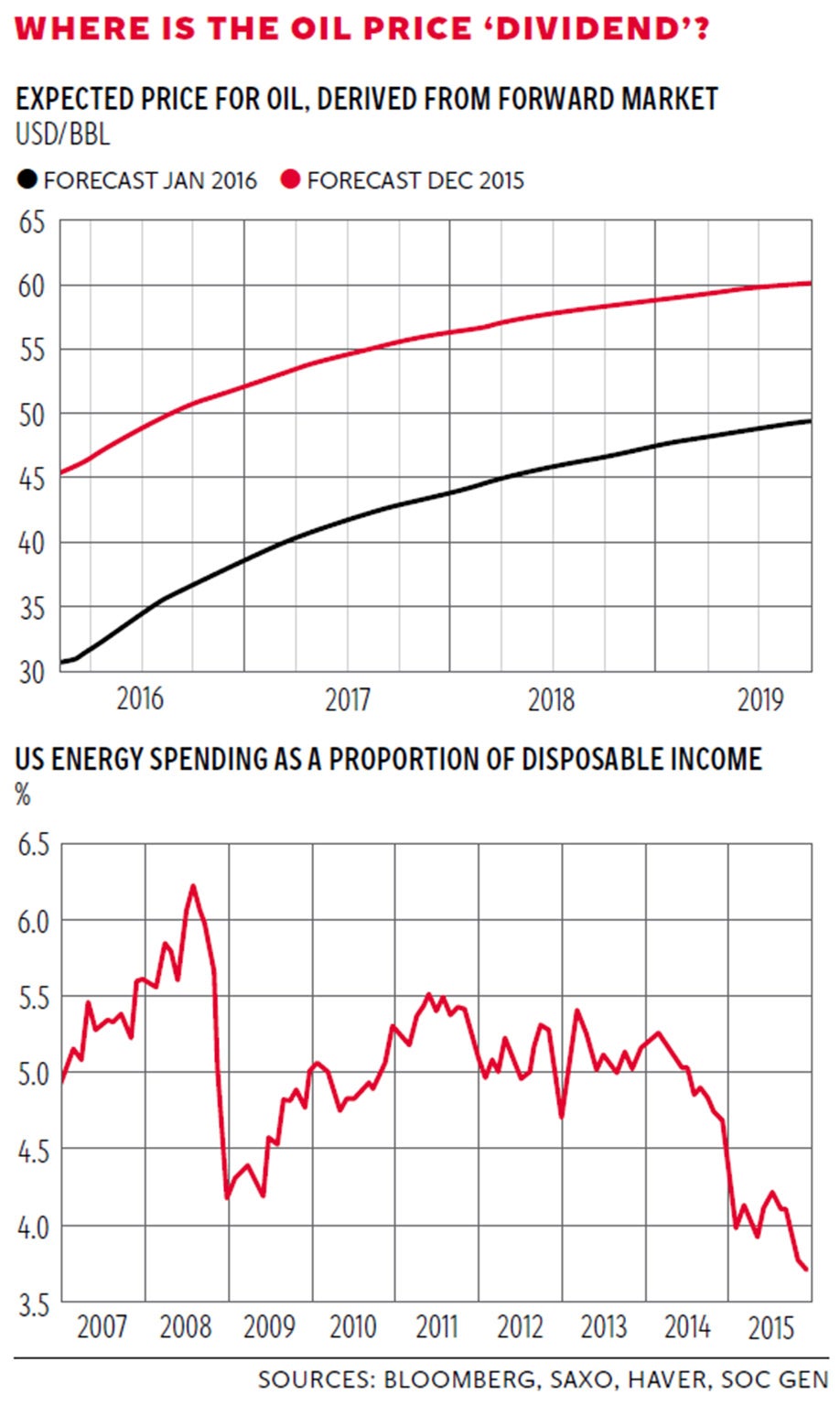

First, the oil price itself. As most of us are aware it has fallen from more than $100 a barrel 18 months ago to close to $30 now. But in addition, in the past month there has been a radical reassessment of where it might go in the next few years. You can get a fix on such expectations by looking at the price of oil for forward delivery. The top graph, which comes from Saxo Bank, shows how a month ago you would pay around $45 a barrel for delivery in February, whereas now it is not much above $30. This change carries on right through the coming years, with the August 2019 price now below $50 whereas in December it was $60.

Remember, these are not forecasts produced by some economist sitting in an office; they represent what a company can buy and sell the stuff for on the oil market. If, for example, you are an airline you can lock into cheap fuel for years ahead. Of course oil may become cheaper still. But it may not. One of my colleagues has just put a fiver with Ladbrokes on Brent dropping below $20 a barrel by the end of this year. He got 25-to-one odds.

So if there is already an oil dividend, expect an even larger one in the months ahead. Is there?

Have a look at the bottom graph, which shows some calculations done by the economic team at Société Générale for the US. As you can see, the proportion of their disposable income that Americans spend on energy has varied between 6 per cent and 3.75 per cent since the end of the boom in 2007. It was pushed up by the surge in oil prices in 2008, and fell sharply in 2009 as the slump cut demand. But now – this is the remarkable point – the proportion of income spent on energy is lower even than then, in fact the lowest for a decade.

So there is a clear dividend. If you say the “normal” proportion of income spent on energy is 5 to 5.5 per cent, it is now 1.5 percentage points below that. Since the summer of 2014, the fall has been a little less than that, about 1.3 percentage points, but given the numbers involved it is still massive. What have the Americans done with this? The answer is that they have spent a bit more but have saved most of it. The savings rate has risen by nearly 1 per cent in the past 18 months.

This is odd. Employment has been strong, unemployment has fallen, so people presumably feel more secure. Maybe the prospect of rising interest rates might encourage people to pare back debt, and certainly a lot of mortgage-holders have taken the opportunity to lock into fixed rate contracts. Soc Gén thinks the explanation lies in uncertainty, which is probably right, but this does not explain why people should feel uncertain about their future finances. You would expect people to spend more as they become more confident that there isn’t a recession round the corner and as the job market remains strong, but the wobble in share prices in the past few weeks must have some impact on sentiment.

It may even be that this latest plunge in the oil price will unsettle things more, if only because consumers cannot quite believe it will last. Still, once the price does settle down, consumers will have a bit more slack in their budgets and that should underpin demand.

These calculations are just about the US and I have not seen a similar analysis of how British and European consumers are splitting their oil dividend between higher consumption and higher savings. My own guess is that consumption in the UK will be determined more than anything else by what happens to the housing market. If it were to tank then people would cut back their spending very sharply and that would more than offset any change in the oil price. But there is a general point here that our living standards have undoubtedly been given a boost by cheaper oil and that this is coupling with the rise that is coming through at last in money wages.

If this is right – and remember a similar boost to living standards is feeding through in Europe and Japan too – then cheap oil will indeed be a key driver of consumption growth through this year right across the developed world.

So there is an oil dividend; it is just difficult to hear its signals because of all the background noise going on in the world economy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments