How can we explain why productivity is lagging behind overall growth?

Economic View

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What is it with productivity? Low productivity has been the less agreeable flip side of the recovery’s high employment. In the early stages of the upswing most people were relieved that unemployment did not rise as much as some of the more alarmist commentators predicted. It seemed natural justice that people without jobs should be able to get them, rather than those in jobs working harder, or at least more effectively, and getting rewarded for that. We, so to speak, informally shared out the work that was available.

But now it is different. Wages are 2.7 per cent up in money terms and, thanks to the dip in inflation, rising at above 2 per cent in real terms. Unemployment is down to 5.5 per cent on the Labour Force Survey measure, and the claimant count (at just below 800,000) is the lowest since 1975. The worry now has switched to labour shortages. Might a tight labour market become the thing that pushes up inflation, that requires a faster increase in interest rates than currently expected, and thereby caps the pace of recovery? Or maybe as the squeeze on labour mounts, we will discover ways of cranking out more output per worker?

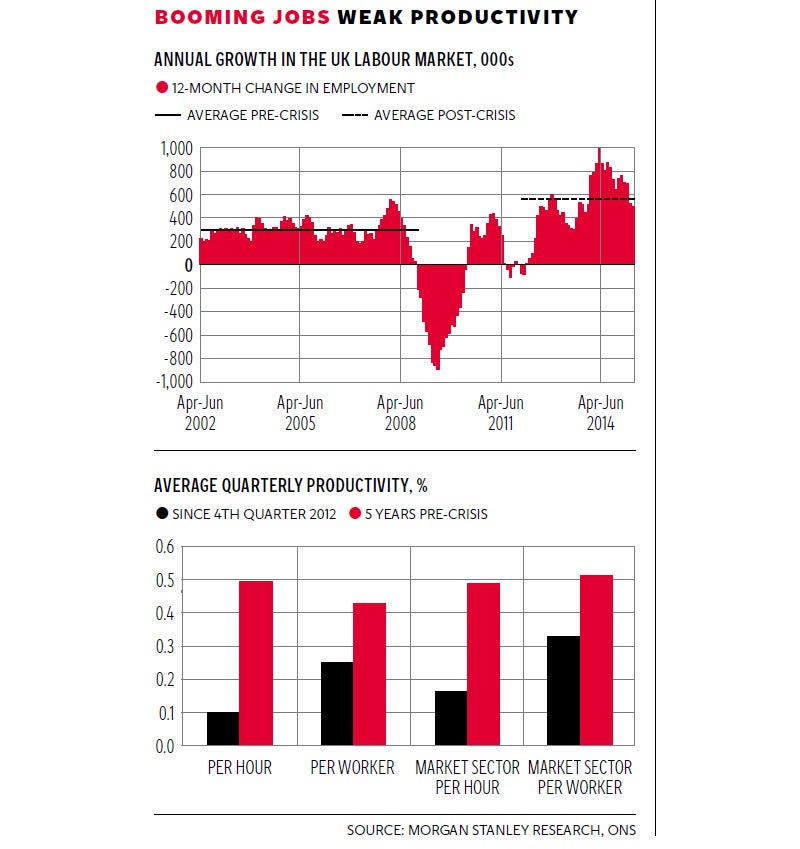

I think the first point to make is that the surge in employment has been remarkable. You can catch some feeling for that in the top graph. During the boom years of the early 2000s we were putting on around 300,000 jobs a year. For the past three years we have been creating jobs at double that rate, peaking at a whisker under a million annual rate. Now the latest data does show some easing of the pace and I don’t think we yet know whether this is significant. But the fundamentally strong market still seems to be in place.

Below the good news graph comes the bad news one. This shows how productivity growth has been much weaker since the end of 2012 than it was in the five years before the crisis. It has been particularly weak if you look at output per hour worked, for before the crisis output was rising at 0.5 per cent a quarter (or 2 per cent a year), whereas in the past two and a half years it has been rising at only 0.1 per cent a quarter.

The figures look a bit better if you take output per worker and better still if you look at the market sector of the economy, which excludes the public sector and non-profit institutions. But there is still a gap. How do you explain it?

These graphs come from a paper by Morgan Stanley that looks at the whole matter. Its main conclusions are that the decline in productivity is mainly cyclical. If GDP is running at 15 per cent below its pre-crisis path, it would be reasonable to expect productivity to be falling short by a similar amount. There is, however, a possible problem: over the past couple of years, a period of strong overall growth, productivity does not seem to have risen by as much as you would expect, given pre-crisis experience.

You can explain some of this apparent shortfall. Part of the problem may be productivity weakness in financial services, an industry where it is notoriously difficult to measure output. (If banks spray loans around, that counts as output, even though those loans turn out to be duff ones. If they are cautious, as they have been, that means their output is lower.) Morgan Stanley thinks we may also be under-measuring GDP. That would certainly be my own view, and it would be consistent with the strong consumption figures if it were so. Finally, the very latest data does seem to show that productivity is starting to grow faster at last.

So can the UK economy go on growing without pushing up inflation beyond the target zone? Productivity will be part of the solution but only part. The labour force will need to go on growing and wage growth will have to remain reasonably subdued.

On the first, things look quite positive. There is always immigration and there are always older workers. One of the astounding features of the UK job market is the way in which immigrants and older workers have boosted the size of our workforce. Since 1997 those two groups account for the entire increase in the workforce. Indeed they account for more than the entire increase: were it not for them the workforce would have shrunk. I think we can assume that these trends will continue. People will continue to come in from the rest of the EU to find work and people beyond retirement age will continue to beaver away at jobs.

Will wage growth remain subdued? Well, there are some areas where it won’t. Skills shortages are nudging up pay in areas such as construction. But Morgan Stanley argues that there may have been a shift in the balance of power in the labour market away from employees and towards employers. I think there is certainly a change in sentiment that will remain even when we are back to full employment, wherever that point turns out to be. One particular reason for thinking this is the shift to self-employment. With 15 per cent of the workforce self-employed and rising, the relationship is becoming more a straightforward transactional one than a source of conflict and tension.

All this is mildly optimistic; only mildly because even if productivity growth were to get back to its pre-crisis norm and even if we are under measuring GDP, there is still going to be a huge amount of leeway to be made up before we get back to the old growth path. Many fear that we may never do so and it is hard to argue against that view. Besides, all the long-standing issues that have held back UK productivity – such as weak investment and lack of training – still exist and it will be a long slog to fix them. But let’s acknowledge that mild optimism: as growth continues we will discover ways of improving productivity, just as we have in the past.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments