Hamish McRae: The economy is booming – but is the growth sustainable?

Economic View: How do people manage to spend more if they are not earning more? We don't know the full answer

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.So what’s not to like? Falling unemployment, rising output, record employment, rising real wages, house prices still climbing, record retail sales, the stock market within a whisker of its all-time high – and the pound at a seven-year high against the euro, just in time for some February Alpine skiing. The data coming through on the British economy is almost too good. We are in a boom, a pre-election boom as it happens, and we all know what happens to those. It is quite true that growth is uneven between sectors; booms always are. It is true, also, that there are parts of the economy that are lagging; that always happens, too. But there is one thing that is undeniable: the economy is creating huge numbers of jobs, and that brings social benefits as well as economic ones.

For those of us who have argued that the economy has for the past three years been stronger than the data initially suggested, it is comforting to have our judgement proved right. I suspect that growth last year will be revised upwards in the next couple of years, probably to rather more than 3 per cent. But all experience tells us that now is the time to ask the awkward questions about the sustainability of what is happening. We need to look forward, and that leads to awkward questions.

Are we still in the early stages of a long recovery or will we start to hit barriers to growth quite soon? Is the UK’s relatively low labour productivity principally a function of a plentiful supply of labour, including foreign labour and people beyond normal retirement age, or is it more the result of poor education and training? Does the widening current account deficit matter? Does the still wide fiscal deficit matter? And so on. As always, the difficulty is to sort out which things really matter and which ones are just noise. That is made even more tricky by the fact that a lot of the numbers are misleading.

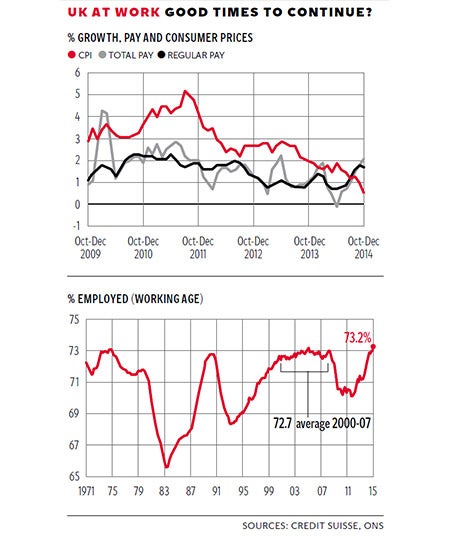

Take the earnings and inflation figures in the top graph. These show that at last, after five years when prices ran ahead of pay, people are now getting real wage increases. But during this time there has been solid overall growth in consumption. So how do people manage to spend more if they are not earning more? We don’t know the full answer, but part of it lies in the fact that earnings are only one source of income: pensions are another as indeed are benefits. In addition, these earnings figures exclude self-employment, now 15 per cent of the total. They also, inevitably, exclude cash payments that are undeclared to the taxman. And, hugely important, they do not take into account the big increase in the numbers of people working, with the participation rate now at a record, as the bottom graph shows.

But while we should be careful in making overly strong conclusions, I think it is possible to make some plausible comments about the ability of the UK economy to sustain several more years of decent growth.

The first comment is that the productivity gap ought to give a lot of scope for sustained growth. Put simply, instead of taking on more people, employers will seek to extract more work out of their existing staff. At the moment it is still reasonably easy to hire more labour in most parts of the country, though skill shortages are beginning to show up. Those skill shortages will increase and that will nudge up pay. Actually, that may already have begun, for private-sector pay from last June to December rose at an annual rate of 3.4 per cent, according to some calculations by Credit Suisse.

Depending on your outlook, you can worry about this apparent tightening of the labour market, or you can celebrate the fact that people are getting better paid. What is beyond dispute is that if labour costs more, employers will try to use it more efficiently. Higher pay will lead to higher productivity.

The second comment is that there is also slack in the labour market that can be filled by part-time and older workers. A quarter of the British workforce is part-time, unusually high by developed country standards. Surveys suggest that about half of these part-timers would rather work longer hours, and while a somewhat smaller proportion would rather work fewer hours, there would seem to be some scope for an increase in hours worked. As for older workers, there are more than a million of them and the number increases every year.

So there is still slack in the labour market, maybe more than most people think. What about other barriers to growth? One popularly cited is private debt. As interest rates rise, maybe starting this summer, will rising debt service costs cut back growth? To some extent it may, but as the McKinsey report of debt noted this month, the country as a whole has been a net payer-back of debt for five years. We are middle of the pack globally in terms of overall debt levels, but while public-sector debt has gone on rising, the private sector level has been falling.

Not only have people been paying back debt faster than the Government has been racking it up; the rise in house and share prices means that net private debt has been falling even faster. So yes, there is a debt problem; but no, it need not hold back growth. Indeed, we need the growth to service the debt and to reduce it relative to the size of the economy as a whole. In any case, I think a rise in interest rates is so well embedded in expectations that it will cause little shock when it comes.

Other barriers to growth include the fiscal deficit, but if coping with the first half of the problem has not stopped the recovery, it is hard to see what damage doing the second half of the job will do to growth. There is an underlying concern about the other deficit, that of the current account, but the data are so mushy that it is difficult to know how serious this is. The foreign exchanges at any rate are ignoring the problem.

We do need to worry. The present boom will not go on forever. When we become complacent, then we run into trouble. But I think rationally there are several years of good growth left. If only we can use those wisely….

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments