Hamish McRae: The chickens have come home to roost for our public finances

Economic Life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is the moment of truth. Tax revenues have collapsed, creating a catastrophe for this Government and a disaster for the next one. They will have to get used to the idea that tax revenues will go down, maybe sharply down, not just this year and next, but probably for longer.

If they don't take this into account and adjust spending, the markets will force them to do so. The UK will almost certainly lose its AAA credit rating this summer as the deterioration in public finances become evident, and while it is unrealistic to talk of the country defaulting on its debts – it can and will print the money to pay them – it will face a decade of retrenchment, rather as it did in the 1980s, as it strives to get borrowing back under control.

There are two problems and it is important to separate them. One is the increase in the national debt brought about by including the balance sheets of the Government-owned and part-owned banks in the national accounts. The other is this collapse in revenue.

The first is principally a balance-sheet issue. It has already pushed the ratio of debt to GDP towards the 50 per cent point, way above the 40 per cent ceiling set by Gordon Brown, and depending on how you should account for banking losses maybe much higher.

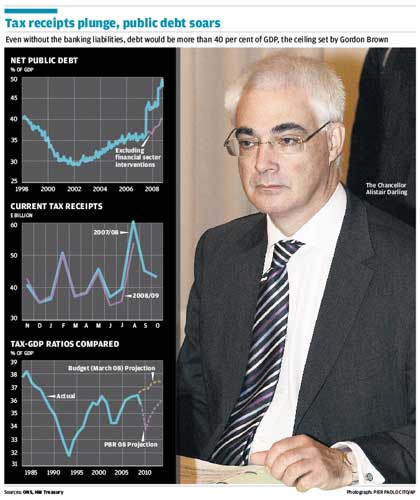

However, even without these additional liabilities, the debt/GDP ratio would have been above the ceiling anyway, as the first graph shows. That is the result partly of higher spending but more of the cut in revenues.

Consequently, borrowing this fiscal year will inevitably rise above the £78bn forecast in the pre-Budget report, and I have seen a forecast of £140bn from Global Insight for the coming fiscal year. The Item Club estimates it will be £130bn. If that proves the case, it would be by far the largest deficit, relative to GDP, ever run by a British government in peace-time.

January is a key month in the fiscal calendar, for it is one when a lot of the big taxes come in. As reported elsewhere, this year they haven't come in on anything like the scale of previous years. Income tax is down. corporation tax is down. VAT is of course down following that cut in the rate, from 17.5 to 15 per cent.

You can see the pattern in the next graph: at the beginning of the present fiscal year, receipts were running above the level of the previous year. Now they are running way below and are set to fall further. Already the dire forecasts of the pre-Budget report have been overtaken by events.

To catch a feeling for the scale of this deterioration, have a look at the third graph, which shows the estimates of the tax take relative to GDP made in the Budget last year and in the PBR. Instead of the line going up, it goes down. But as I say, that is already too optimistic. We will have to see whether the Budget on 22 April comes up with more realistic numbers, but in a way it doesn't matter what our poor Chancellor says; what matters is what happens in the months ahead.

So what will happen? It is very hard to be optimistic about revenues. The problem is not just the recession, for that has barely begun. The problem is structural. Too much of the revenue comes from high-earners in London and the home counties. The top 1 per cent of income-tax payers contributes more than 20 per cent of income-tax revenue.

People reasonably bleat about bonuses, but those bonuses make a huge contribution to tax revenues. Banking contributes 20 per cent of corporation tax, and it will not make significant profits for several years, as the swaths of bad debts are written off. It gets worse. The housing slump has knocked a hole in the stamp-duty take, and the stock-market slump has reduced the contribution made by capital gains tax.

As employment declines, so too will national insurance contributions. Until consumption recovers, VAT cannot recover whatever rate it is charged at.

It is hard too to be optimistic about spending because so much of the Government's spending is fixed. Even if you clamp down on spending, as Gordon Brown did in the first period of his office as Chancellor, it takes a while for that to have an effect. So even if it were desirable, and there are good reasons not to cut public spending in a slump, there is not much that can be done for the fiscal year that starts in six weeks' time.

Everything will happen after the next election, which my colleague Steve Richards tells me will probably be in May 2010.

And then? I don't think this can be fixed in the life of one parliament. So the aim during the next parliament, assuming it runs to 2014, will be to stabilise the situation. The first thing to do will be to keep the deficit at a level where it can be financed and then to chart some credible path towards a sustainable level.

Until a few months ago, you could have a debate as to whether the burden should be borne mainly by cutting spending or mainly by increasing taxation. Now it is clear it will have to be both. It would be nice to say that this is a political choice, but actually this has gone beyond politics. The harsh arithmetic makes radical measures inevitable, and the difficult task for the next government will be to sustain support for these measures.

This leads to a bigger issue, which is that we are getting a taste now of the sort of fiscal constraints that will govern political choice for a generation.

The UK's present plight is partly a result of recession but much more one of structural imbalance. We don't pay enough tax for the level of spending we have sought to maintain.

Unfortunately that imbalance will grow, largely for demographic reasons. An ageing population will require more spending on health care and pensions. A stable, maybe falling, working population will have to fund those services. So it is not a question of paying more tax for better services. It is paying more tax for the same level of services – and maybe even for worse or at least cheaper services. That is a very difficult proposition to sell to an electorate.

Until now it has not been necessary to confront this prospect, for three main reasons. One has been the relative strength of tax revenues, for the reasons noted above. The second has been the general buoyancy of the economy, itself a result of excessive borrowing, public and private alike. And the third has been a rise in the size of the workforce, partly from inward migration and partly because people above retirement age have remained in the workforce.

Now the first two engines have been put into reverse thrust. We have to fly on the third alone. It is a different world, one of fiscal constraint, and if you want to take a symbolic moment when we moved into it, last month was not a bad time to pick.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments